In recent years, there have been times when sales broker Alex G. Clarke has been fine with people thinking he’s a bit nuts. It started when Denison Yachting became one of the industry’s first companies to accept bitcoin as payment for boats. Clarke did the firm’s first $10 million-plus bitcoin deal.

“Everybody thought we were crazy,” he says. “Nobody really knew how mainstream it was going to be or the applications for it.”

If he had taken even part of his commission back then in bitcoin, he’d likely have the cryptocurrency equivalent of millions of dollars today. So, when his tech-savvy clients started talking more recently about an emerging technology called non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, he paid attention.

“I’ve been following this tech probably a little closer than most brokers,” he says. “We see this technology with the NFT as having so much potential to kind of merge the old-school guy who wants a really nice yacht with the next generation, the new money, the tech-savvy people who understand the NFT applications.”

More and more these days, people are starting to think like him. Some of the best-known names in yachting, including the builders Oceanco and Delta, and award-winning designers Greg Marshall and Dickie Bannenberg, are either dipping their toes in the NFT world or trying to build the future that the technology appears poised to make possible—both in the digital space and with yachts in real life.

“The reality is that we’re all feeling our way around this,” Marshall says. “We know we’re onto something powerful; we just don’t fully see the whole story yet.”

The Basics of NFTs

Think about the internet that existed 20 years ago. Anyone could build a website, develop an audience and generate advertising revenue. If the website’s owner wanted to move that audience to a different platform, he could do so easily.

That version of the online world is what tech gurus call Web 1.0. Today, we’re living in what they describe as Web 2.0, where huge companies such as Meta (formerly Facebook) and Google have positioned themselves between website developers and audiences. Anyone trying to promote a website today encounters things such as algorithm changes that can shrink an audience’s size overnight.

Rebalancing that equation is the thinking behind Web3, which the tech gurus are creating now. Its foundation is technology called the blockchain, which is decentralized. It’s not owned by any one company but is instead managed by a peer-to-peer network. Blockchain technology creates blocks of data that cannot be modified—which is another way of saying they’re non-fungible. Whereas anyone can swap a dollar bill for another dollar bill, each NFT that gets minted is a one-of-a-kind item.

“It cannot be duplicated or replicated,” says Zach Mandelstein, founder of the digital yacht dealer Cloud Yachts. “It’s one-of-one because it’s built on the blockchain, which verifies that it is a unique item. It’s like a Gucci-purse authenticator.”

And an NFT can hold a heck of a lot more stuff than a purse. It can digitally store, say, not only the design plans for a superyacht, but also all the emails and contractual records that went into building that yacht, in a way that can be offered to the yacht’s next owner as part of a sales package.

“You used to be able to buy a used car, and the story behind it was whatever you were told,” Mandelstein says. “When Carfax came along, you got to see everything—the mileage, everything. This is a similar paradigm shift. With these NFTs, we can upload thousands of data points into this new-build process, right down to billable hours with the technicians.”

What should be inside those thousands of data points? That’s what early adopters of NFT technology are trying to figure out. Some are building things such as the digital playground known as the metaverse, where people will live whole other lives that they experience through digital goggles. Others are thinking about the technology as a next-step progression from existing tools such as digital yacht modeling, with real-world applications.

“This extension into the NFT world—it feels like a logical one,” Bannenberg says. “On the technical side, it doesn’t feel like a particularly big step, but it does require getting your head around the concept of what somebody is able to acquire, what they get from it, over and on top of a 3D image. What other underlying value can we give? What does it offer the buyer that is interesting?”

Piecing It Together

Marshall and his team started thinking about NFTs because, for the past four years, they’ve been doing a deep dive into holographic design. They’re working toward a future where people can put on a pair of goggles and experience an augmented-reality version of yacht construction and maintenance.

“Everybody working on an engine, for example, can be on a different continent,” Marshall says. “We’re probably a year or year and a half away from fully commercializing it. It’s pretty wild, what it’s going to do to our industry.”

Making that kind of technology work involves building a massive library of 3D components. Consider every hose, seacock and other component aboard a yacht. Each one needs a digital equivalent that the technology can recognize. “We’re coming up on a million of these pieces, every component we use, from filters to engines to galley sinks,” Marshall says.

So, he started looking for ways to back up all that data. The search led him to NFTs, which could handle the data volume in a way that he sees as being “a safety-deposit box” because the blockchain creates the one-of-one, non-fungible record.

At the same time that Marshall was trying to solve that problem, he also was talking with Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut about donating his library of plans in the future. Again, the potential of NFT technology came to mind.

“The amount of data that we have produced is just insane,” he says. “Going back and being able to catalog it all and archive it is a massive job. So, we wondered: Could we NFT each project? That would capture all the digital data.”

Marshall started researching NFTs in more detail, and he found Mandelstein at Cloud Yachts. Mandelstein’s background is in intellectual-property management, including protecting things such as trademarks, and he got a yacht-broker license almost a decade ago as a side hustle. His combination of skills helped him see the potential value of all the data Marshall was trying to store and transfer—and that other designers would likely want to store and transfer too.

“I knew there were a bunch of designs from guys like Greg Marshall and Dickie Bannenberg that [were] just burning a hole in their computers,” Mandelstein says. “It was like cash burning a hole in a pocket. It is valuable intellectual property that could be monetized.”

For Marshall, even thinking about his yacht designs that way was new.

“I could see instantly that Zach’s perspective about the value of an NFT was totally different from mine,” Marshall says. “We pieced together each other’s versions as we were talking.”

Yet More Pieces

Clarke, meanwhile, was thinking about NFT technology from the perspective of a sales broker. He had heard about real estate deals that incorporated NFTs into the sale price, and he started to think about how something similar might work for yachts. He landed on an idea that he thinks of as “smart contracts.”

“If you build a yacht today, you’re going to have your manuals, your software, everything about the build, your blueprints, your build specs—you can take all that and organize it on an NFT and put all that metadata together,” Clarke says. “Inside your NFT is a very well-organized thing that’s only accessible by you or by a select few people. If you want to sell the boat, you can hand over this NFT collection along with the yacht. My vision is that the NFT will stay with the boat. The appealing part on the brokerage market is that all the data is nicely organized and easy to transfer.”

To his thinking, as any yacht progresses from owner to owner, new NFTs could be minted to add even more value.

“Owning an NFT is like owning a little vault,” he says. “It’s [an] all-in-one clean package. Instead of going back and forth between attorneys with a bunch of binders, even if you’re going through class or flag regulations in the future, you could keep that whole history organized in there. Things like that, it could be very useful for the owner, the second owner and the third owner. Nothing will get lost in translation over the life of the yacht.”

As the metaverse continues to be built, at some point, all of that data could be used to create digital versions of real-life yachts. Owners buying an NFT today could be investing not only in plans to build a vessel that they can take to the Bahamas right now, but also in a digital version of that same vessel that could have additional value once everyone is strapping on goggles and looking for virtual hotspots and marinas.

For instance, Clarke says, maybe “we’re going to give you a slip in the metaverse as part of the transaction. Who’s to say that it doesn’t become like buying a slip in Monaco, and it’s worth $200,000 or $400,000 or $1 million in the metaverse in the future?”

As Marshall sees it, there’s also potential value in today’s NFTs being used as the foundation to build tomorrow’s real-life yachts. A lot of the same data that can be used in the metaverse can also be used at brick-and-mortar shipyards.

“There’s also a lot of things like little sketches that, say, a craftsman will make on the floor and sends in an email to an office. Right now, all those little sketches are languishing. Nobody is collecting them,” Marshall says. “The ability to collect all those kinds of things with an NFT is extraordinary. Now you’ve created a digital asset. That asset can then be licensed out to build a second one, a third one or a fourth one.”

Creating those kinds of initial assets is happening already. In March, a businessman from Texas bought an NFT of a 110-foot Marshall design. It will be used to build a real yacht, at a cost of about $12 million. Then NFT No. 2 will become available.

“We will use the NFT from No. 1 to develop No. 2,” Marshall says. “Now, again, we are feeling our way around this. As I said to the owner of the project, I can guarantee we’re going to make mistakes. We made one step, our very first step, we screwed up, and I said, ‘OK, good. We’re one for one.’ We don’t know where or how it’s going to go, and we are trusting that, as gentlemen, we’ll figure it out as we get there.”

Real-Life Access

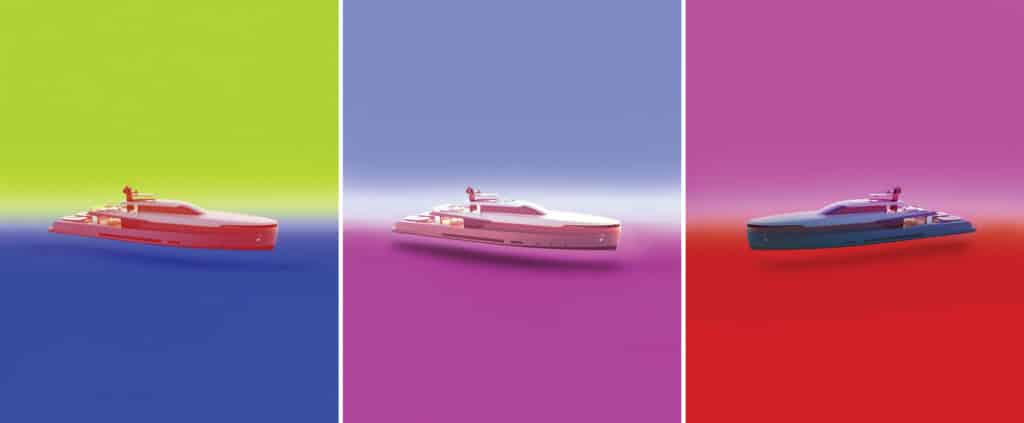

Bannenberg, meanwhile, worked with Cloud Yachts to offer one of Bannenberg & Rowell’s 131-foot designs as an NFT earlier this year at the Palm Beach International Boat Show in Florida. There were five versions—each a unique piece of digital art with backgrounds of different colors—and whoever bought them also got access to the design team in real life.

“It’s a standing invitation to come and spend a few hours in the studio and have an exploratory design meeting,” Bannenberg says. “They can come to London, or we can do Microsoft Teams or Zoom. And then we’ll take it from there.”

He’s also thinking about some of the possibilities that Marshall is considering. Bannenberg’s father is Jon Bannenberg—often called the “father of modern yacht design”—and the Bannenberg & Rowell firm owns all of the elder’s drawings. A couple hundred of those designs could be converted from 2D ink on film into NFTs, and then used to create some of the metaverse’s first, well, classic digital designs.

“Everyone says there’s an element of the Wild West to this exploratory stuff, but this is how other things started too,” he says. “Right now, it seems to be at a very simple level. Things that are only 18 months old suddenly feel ancient compared to the possibilities.”

Nobody is quite sure what consumers will find valuable. When Marshall’s NFTs became available, he was driving along the California coast. “Every once in a while, my phone would ping, and another one had been sold,” he says, adding that he was as surprised as anyone. “Another $300 or so would show up in my account. A couple of them resold.”

From a designer standpoint, that kind of automatic payment is appealing—because the same kind of payment happens with a full-on yacht design.

“Before, I would have had to send an invoice and hoped that the guy would pay it, and he might not pay it for 30 days,” Marshall says. “Moving forward, if you build No. 20 of this boat, I don’t have to think about it. I don’t have to get hold of a shipyard and see if they sold another boat, and you have this awkward conversation about how they owe you money. It’s a tough thing collecting on the royalty sometimes. In this case, it happens automatically.”

Who’s buying these first NFT offerings? Clarke, for one. He’s trying to collect all the No. 1 NFTs that major yacht designers offer—just in case being first ends up being significant.

“I was told it doesn’t matter if you have No. 1 or No. 5, but I’m thinking there is a difference,” he says, adding that it all helps him understand the ways future clients may want to do business. “At Denison, our escrow account is at JPMorgan. They just opened their first office in the metaverse to service clients there. So, if you want to go into the metaverse, we are working with them. We could go and say: ‘Mr. Buyer, when you’re doing your payments, we work with JPMorgan. We can buy your slip for your yacht in the metaverse. Our banker is already there.’”

Where Is the Value?

That’s the real nut of the question. For younger buyers, the technology sells itself, Mandelstein says.

“I’m meeting the owners of shipyards now, and the dads get it, but their sons are tripping out about how cool this is,” he says. “The sons are all over it. They think it’s the most exciting thing they’ve seen. We don’t know what’s going to come out of this, but it’s something really special that wasn’t there before.”

Clarke sees those sons as the yacht buyers of the future—who will expect NFT-based technology to be part of the experience.

“My thought was taking part of an interior on a 63-meter and putting in a media room with two zero-gravity chairs,” Clarke says. “You get one of your buddies on board, you put on your goggles and sit on those chairs, and you go in the metaverse and say, ‘Here’s the boat.’ You get on the boat in the virtual world as you’re actually doing it on a yacht in the real world. For me, that’s the cool stuff you can do to make it a lot of fun.”

Marshall, meanwhile, is using his mother-in-law, Rose, as a guinea pig to figure out how to get traditional yacht buyers interested; many of them have no desire to strap on goggles and enter a digital playground.

“She’s in her 80s,” Marshall says. “We put HoloLenses on her head and walk her through the process. When she puts the headset on, our person, Sara, pops up digitally from a different location and walks Rose through how to use this. Digital Sara will touch Digital Rose’s wrist and say: ‘See this button right here? Push this button.’ We intentionally hired people who know their way around engine rooms and things, but who don’t know the tech. If it didn’t work easily, we wanted to build the tech and start over. We’re doing that today. That part of it is incredible. It’s crazy how powerful that is.”

Mandelstein is betting that harnessing even a small piece of that power is something yacht owners will want to do.

“You can’t stand in the way of progress,” he says. “Most big corporations have figured out that this thing is coming. Mark my words: In a few years, there will be NFT managers like there are social media managers in every corporation. We’re still figuring out the best use for this technology, but the revolution has already begun.”

On Capitol Hill

Congress hasn’t yet moved to regulate NFTs, but in January, Dapper Labs became the first firm to register to federally lobby on issues related to NFTs. The company’s head of government affairs is a former member of the Federal Communications Commission.

In the EU

The European Union was considering rules this past spring that would require issuers of NFTs to centralize and register. The rules would be part of what’s known as Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation if passed into law. The European Parliament says it is worried about the use of NFTs in money laundering and other scams, so it’s talking about requiring that issuers be “a legal person” rather than a decentralized entity.

Luxury Autos

McLaren, maker of luxury supercars in Britain, dropped NFTs called the Genesis Collection. The collection has five tiers, with a limited number of each (as few as 100 or 1,000) available for purchase. Some tiers aren’t open to buyers at all, and instead will be gifted to select members of the McLaren community.

The Silver Screen

If lawsuits are an indication of value, then Hollywood sees NFTs as having plenty. Miramax Studios is suing Quentin Tarantino over the director’s attempts to sell NFTs of his screenplay for Pulp Fiction. Tarantino’s contract gives him the rights to sell copies of the screenplay, but Miramax is arguing that the 1993 deal could not have reserved rights to sell NFTs because the technology didn’t even exist back then. How much money is at stake? The first Tarantino NFT sold for $1.1 million in January.

Louis: The Game

Players working their way through Louis Vuitton’s smartphone app called Louis: The Game can find 30 embedded NFTs along the way. Each one is considered a collectible that can only be found within the game. This spring, the company announced that players who reach the end can expand their experience into additional levels, with new NFTs to win.

The Foodverse

Celebrity chefs Spike Mendelsohn and Tom Colicchio launched an NFT project called CHFTY Pizzas in March. They plan to sell 2,777 of the NFTs, which will give buyers access to exclusive channels where they can access experiences such as master classes and pizza parties with various celebrity chefs nationwide. Each CHFTY NFT avatar is one of a kind and intended to appeal to collectors. The team also plans to help other chefs launch into the world of NFTs in the future.