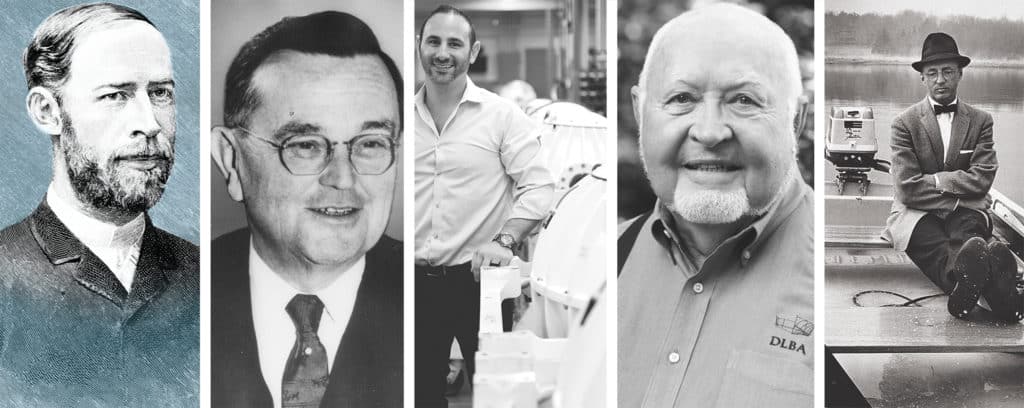

Heinrich Hertz: Spark of Knowledge

As mariners, we can’t claim Heinrich Hertz all to ourselves. His discovery of radio waves has had an impact far beyond the watery world. Still, his work has played a key role in maritime communications and navigation that is, perhaps, unmatched by any other scientist’s.

When he constructed his “oscillator” and then used it to jump sparks between a gap, creating pulses of electromagnetic waves that were detectable several feet away through thin air, Hertz wrote: “I do not think that the wireless waves I have discovered will have any practical application.”

Within a decade, radio signals would be broadcast across the Atlantic Ocean.

To one degree or another, we owe Hertz credit for our VHF radios, radar, satellite communications, GPS, cellphones and even the microwave ovens in our galleys. Hertz also discovered the photoelectric effect, which formed the base of knowledge that led to our modern concept of solar power. He advanced experimentation with cathode rays and contributed to the field of theoretical mechanics — all before dying at age 36, in 1894. And yes, the frequencies we call hertz are named after him.

Russell Slayter: The Weaver

As vice president of research and development at Owens Corning, Russell Games Slayter was credited with inventing fibers of glass in the form of individual strands that were long and flexible enough to be woven.

Of all the past century’s inventions, it’s hard to argue that any has been more impactful on the marine industry than fiberglass.

Yet when Slayter (along with employee Dale Kleist) developed a process for creating glass wool and applied for the patent in 1933, boats were probably the furthest thing from his mind. The first commercial use of fiberglass was as insulation. It wasn’t until 1941 that Owens Corning produced fiberglass-reinforced plastics, or FRP, which the U.S. military used to replace some of its aluminum.

A builder of small wooden sailboats named Ray Green is often credited as being the first, in 1942, to build an FRP boat: an 8-foot dinghy.

Today, according to the National Marine Manufacturers Association, 57 percent of all mechanically propelled boats are built from fiberglass — a reality that wouldn’t be possible without Slayter’s contribution.

Seakeeper: Balanced Behavior

Seakeeper’s gyroscopic stabilization units are transforming boating and yachting as we speak. These moment-control gyroscopes — utilizing the same technology that stabilizes the International Space Station — reduce a boat’s rocking and rolling by as much as 95 percent.

The concept behind Seakeeper is to do away with the seasickness, anxiety and fatigue associated with rocking and rolling on board. Anyone who’s been on a Seakeeper-equipped boat can confirm that the results are quite real, and shockingly evident from the moment you leave the slip.

“When John Adams and I started Seakeeper, we didn’t just want to create a new toy,” says co-founder Shep McKenney. “We wanted to change the entire boating experience at its core. Seakeeper is now something that boat owners expect, and we’re working every day to continue to make that expectation a reality, even for smaller and smaller boats.”

Seakeeper: How it Works

1. That’s Fast: Inside the Seakeeper’s housing is what looks likean aluminum orb, and inside that vaccum-sealed orb is a flywheel.

The flywheel sits on a vertical axis with upper and lower bearings supporting it as it spins at 557 miles per hour. For perspective, that’s about the average air speed of most commercial jets.

2. Keep Cool: For the flywheel to spin at 0.75 mach, it needs to stay cool. The manufacturer uses a cooling system mix of seawater and glycol.

3. Steady Eddie: Each Seakeeper has a computer-based active control function that is always adjusting for the sea state in real time, applying the required anti-roll torque to keep a vessel on even keel. The gyro moves fore and aft, providing the stopping motion to port and starboard.

4. Product Lineup: Seakeeper’s current product range works on boats and yachts as small as 27 feet length overall and as large as 85-plus feet length overall.

Don Blount: Designed for Destiny

Naval architect Donald L. Blount’s fascination with hydrodynamics began when he was a student at Virginia Tech. It turned into a 20-year career designing small craft for the U.S. Navy, and culminated with serving as the head of the Department of the Navy Combatant Craft Division.

He founded Donald L. Blount and Associates in 1988, and ever since has played a role in boat designs ranging from Rybovich convertible sport-fishers to Jupiter center-consoles to the (former) Spanish royal yacht Fortuna — at least 500 designs in all, as near as he can figure.

Under his leadership, the firm has performed groundbreaking research in hydrodynamics and aerodynamics, including the use of test tanks, wind tunnels and computational fluid dynamics, all to make boats ride as quickly, efficiently and comfortably as possible through rough water.

And yet it’s not his designs and engineering that Blount sees as his greatest achievements. He instead cites his written works, including Performance by Design: Hydrodynamics for High-Speed Vessels.

“It’s the books and papers I’ve published that have meant the most to me and, I think, to the boating and boatbuilding community,” Blount says. “I love taking marine technology and putting it into street language. Making it understandable, so it’s useful to a wider range of people.”

Dick Fisher: The Unsinkable Legend

Few companies have enjoyed long-term success as smashing as Boston Whaler’s, and few boatbuilders have attained the status of Dick Fisher and his “unsinkable” boats. Fisher’s construction method, the basic concept of which is still being used to create Boston Whalers today, results in a boat that truly cannot sink.

In 1957, Fisher, a Harvard graduate, filed for patents protecting his process of injecting liquid foam into a boat’s hull, creating a one-piece glass-foam-glass sandwich. A year later, the Boston Whaler 13 was introduced at the New York Boat Show. Today, the tools and the foam are more advanced, but the concept remains the same — and Boston Whalers remain unsinkable.

“Dick Fisher launched a concept of unsinkability that continues to define us as a company and a community,” says Boston Whaler President Nick Stickler. “More than a trait or a tagline, unsinkability is a way of approaching the world: excited to grow, eager to push the envelope, invested in the process and our team, and enjoying the journey.”