In a market rife with the grand creations of many gifted yards, the 56-foot Picasso, from a small yard in Stuart, Florida, has been turning heads. She is a blend of modern materials, interior beauty and Old World craftsmanship whose 70,000 manpower hours are impossible to appreciate without the benefit of a little history.

Addison Whiticar arrived in Florida in 1917 to commercially fish the rich offshore waters. Tourism increased after World War II, and the Whiticar charter fishing fleet was born. Addison’s son, Curt, designed and built the boats at a small yard on Willoughby Creek in Stuart, and brothers Jack and Johnson chased spindle-beaked sailfish offshore. A number of charter customers, impressed with the quality and performance of Whiticar’s creations, soon commissioned their own boats. Over time, Curt and his brother-in-law John Dragseth built boats and the yard’s reputation. Today, Whiticar Boat Works is in the capable hands of Curt Whiticar’s son John and Dragseth’s son Jim. Some of the 20 craftsmen who focus on new construction have been with the yard since the early days.

The cornerstone of Whiticar’s reputation lay in Curt Whiticar’s slippery hull form and the stout, carvel-planked construction he employed when he founded the yard in 1947. Early Whiticars were tough, businesslike boats designed to negotiate the treacherous St. Lucie Inlet and the Gulf Stream’s steep rip.

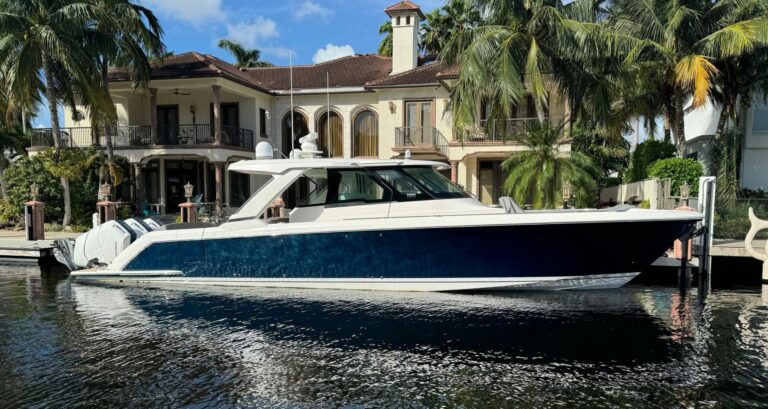

Picasso is far from a simple boat, and the methods used in her construction are thoroughly modern. Yet her roots as a good sea boat remain clear, and her quality is a reflection of her builder’s experience.

Hull design at Whiticar is evolutionary, not revolutionary, but Picasso’s hull form is in no way traditional. To the contrary, it bears little resemblance to her doughty predecessors. She is hard chined with a pleasantly raked stem and a deep forefoot with straight sections that moderate aft to a transom deadrise of 12 degrees. A chine rail forward controls spray and melds into a chine flat that runs aft from amidships.

As demand for faster boats increased over the years, Whiticar reduced keel depth. Picasso has no keel, and thus no unwanted hydrodynamics, as evidenced by our sea trial. Picasso performs well, powered by a pair of 1,150 hp Detroit Diesel/MTU 12V 183s with 1.75:1 ZF gears and 30-by-38 four-blade propellers. This is a straightforward, proven propulsion package and a perfect choice for this yacht. Her hull is easily driven and remains on plane at less than 15 knots. From a dead stop, she reached full speed in 15 seconds without clouds of black smoke. Seas were light, and spray broke cleanly from her chine, indicating a dry ride in a seaway. She was stable at rest and maneuvered easily. Her electronically controlled trolling valves let her loiter at less than a knot and cut out automatically when the throttles are slammed in the heat of battle.

If there is a secret to the performance of Whiticar’s boats, it is that they tend to have a bit less chine beam forward than most conventional production boats. Production builders pressured to focus on interior volume have unfortunately abandoned this vestige of traditional design.

Carvel planking is long gone at Whiticar, which has perfected modern cold-molded construction techniques. Picasso is an example of the yard’s willingness to exploit new technology. Working with naval architect Robert Ullberg, Whiticar blurred the line between cold-molded wood and composite construction. Picasso’s bottom is triple diagonally planked 3/8-inch solid mahogany. Epoxy resin is used, and each mahogany layer is separated by 20 ounces of fiberglass cloth, then vacuum-bagged in place. Hull sides are double diagonally planked. The stem, chine and keel are laminated mahogany, and stringers are laminated fir. Bulkheads and internal frames are marine plywood.

The hull is covered with a Kevlar-fiberglass blend and finished with a linear urethane coating inside and out. The superstructure is built in a similar fashion, although the house and bridge faces are fiberglass-foam core sandwiches. The decks are fiberglass over marine plywood, and laminated fir I-beams with lightening holes provide support. The machinery space is accessible from the cockpit and has a mirror-like finish. Every wire, hose and pipe is thoughtfully placed.

While the detail and execution of Picasso’s structure is significant, her interior attracts the most attention. Most of the solid teak stock used in her interior and exterior came from a single tree. Pictures only hint at the quality of fit and finish. The real artistry of what Whiticar’s craftsmen accomplished is hidden.

A raised panel interior is complicated enough, but aboard Picasso, every door and panel is cored with honeycomb to reduce weight. Interior designer Sam Rowell created the design, and industrial designer Ted Black detailed it using sophisticated computer modeling. The result is a traditional look with spectacular accents.

Features such as the carved teak-and-ebony drawer and cabinet pulls, and the master head’s teak-and-ebony sink, demonstrate a level of craftsmanship rarely found these days. Design details, such as the lighted mirror that emerges from the vanity with the push of a button, are among the Rube Goldberg touches common on modern Whiticar designs.

Picasso’s interior arrangement incorporates a large, open saloon/galley area with a 42-inch plasma TV and a theater-quality sound system. Her two-stateroom/two-head design is rare in a 56-foot convertible, what with today’s trend of selling boats by the bunk. Considering her master suite’s volume and comfort, I would find it easy to send extra guests ashore. A large tackle stowage area is cleverly hidden behind sliding panels in the passageway.

Whiticars have always been respected players in the tournament circuit, and this yacht is equipped to perform as a fishing platform. Her teak cockpit offers an uncluttered work space and is fitted with a fighting chair, a live well, a bait prep center and a freezer. Her bridge has a helm pod on centerline, an impressive built-in electronics console and L-shape seating forward. She is fitted with Rupp Tournament riggers, and her tower, built by Jack Hopewell, is a work of art.

Building a yacht like Picasso will cost more than $3,500,000. That’s quite a bit of money for a 56-foot convertible, but few, if any, other boats compare. That makes her a good value.

Whiticar is about to complete an additional construction facility, and construction of a 76 Whiticar will begin when the building is done.

Contact: Whiticar Boat Works Inc., (561) 287-2883; fax (561) 287-2922; www.whiticar.com.