The 2019 Winter Vashon Race was so bereft of wind that it took us almost eight hours to sail 12 nautical miles. As our crew struggled to work even the most minuscule wind shift, evening fell hard onto a fleet that had been expecting a daysail. Some boats, including ours, turned on their masthead tricolor lights and dimmed their instrumentation screens, while others took a more hodgepodge approach. Watching this scene unfurl, it occurred to me that networking these devices and creating one-switch-to-flip operating modes would be a vast improvement.

Today, this technology is available in the form of digital-switching systems. They give owners more control over a vessel’s onboard equipment than traditional switching systems, while delivering other important benefits.

Traditional electrical systems include panels, fuses, breakers and, sometimes, lengthy wire runs. This approach works, but the automotive and aviation industries—where lighter weight and redundancy are vital—pioneered digital-switching systems. Digital switching has existed in the marine sector for about 20 years, with control over yacht systems increasing every year.

Digital switching essentially replaces analog equipment with digital componentry, such as controller-area-network buses. The systems are software-driven and upgradable, and are decentralized with no panel or governing computer. They allow discrete systems and networked instrumentation to communicate using a message-based protocol. These messages are called parameter group numbers, and they’re transmitted over a data backbone that shares PGNs across the entire network.

In a traditional system, AC or DC power flows through a wire to a fuse to an analog switch and then to the load. Digital-switching systems send power to a current-measuring device and then to an electronic switch before sending it to a load. That process means the wires can be smaller gauge and run over shorter distances. Moreover, digital- switching systems divide a yacht into zones controlled by an output-interface module that has some level of embedded intelligence.

“One great advantage of a digital-switching system is that we take the power to the loads,” says Phil Lee, the field application engineer for Octoplex. “You can reduce the weight of the wires by 45 [to] 50 percent, making the vessel more fuel efficient, and copper wire is expensive. This approach shortens and simplifies wire runs, reducing the chances of voltage drops while also saving money. With digital switching, you can control multiple circuits from a single button, or you can control a single circuit from multiple places. You don’t need current in the switch.”

A digital-switching system informs a switch that it’s been activated or deactivated via an electrical signal. This process makes digital switching ideal for yachts with multiple helms because installers don’t need to wire a switch in two places; instead, they program the system.

“With digital switching, there’s built-in intelligence along the pathway,” says Matt Elsner, product manager for CZone, which makes systems for recreational boats. “It’s a more efficient trigger from the trigger point to the load.”

Critically, digital-switching systems use pulse-width modulation, which is a way of reducing the amount of power an electrical signal delivers. This method allows users to, say, dim lights or adjust the air conditioner in controlled increments. Better still, if a vessel is connected to the internet, then owners can usually monitor and control all networked equipment from afar.

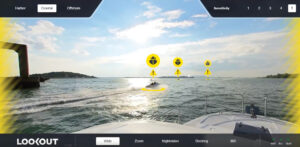

Unlike traditional switching systems, which use hard-wired switches, digital-switching systems use virtual buttons on touchscreen displays. Manufacturer depending, these displays could be proprietary, or they could be third-party tablets or multifunction displays. (There can be back-end monitoring, troubleshooting and tech-support advantages to using a manufacturer-supplied digital-switching display.)

All digital-switching systems send PGNs across their networks, how- ever, not all PGNs are created equally. For example, some manufacturers only use standard NMEA PGNs that can be read by all N2K-compatible equipment, while other manufacturers employ proprietary PGNs that may require additional equipment. Moreover, some PGNs have priority over others. For example, digital-switching PGNs are prioritized over navigational PGNs. Manufacturers typically split the two networks so navigation doesn’t suffer.

“Digital switching delivers integration onto a common network to control all circuits in a system,” Elsner says. “Everything that you can do from an analog system can be consolidated into a single screen.” This latter point is especially germane to yachtsmen who want all-glass helms.

Repairs are handled through a system’s decentralized modules. For instance, Elsner says, with a CZone system, once a module has been configured for a yacht, it shares this programming with the entire system: “If a module goes bad, you can replace it, and the other modules will ‘teach’ it the language.” And all digital-switching systems have overrides. These can exist as dual CAN networks aboard larger installations, or they could be removable blade fuses on smaller systems.

This decentralized architecture makes adding new equipment a plug-and-play task. “As you add loads, you can add modules if the runs become unruly,” Elsner says. “This simplifies the maturation of the boat.”

More immediate, digital switching simplifies onboard operations. Its modes mean a single tap controls multiple circuits. These modes can include everything such as “night cruising” (running lights or tricolor on, instruments dimmed), “party” (strobe lights and refrigeration on) and “away” (lights off, security system on).

Unlike other marine-electronics gear, digital-switching systems are usually builder-installed. “The builder tells us what size wires they’re using, and we set the [parameters],” Lee says. “We can never increase current on a circuit beyond what it’s rated for.”

Owners contemplating a new build may want to consider using a digital-switching system. Not only will it save money in the long run, but it will also make operations far smoother than trotting to the electrical panel or individual instruments every time a three-hour tour morphs into the long and winding road.

Real-World Constraints

Digital-switching systems offer far more redundancy than traditional switching systems, however, one inherent limitation involves running out of DC power while cruising. “If you go dead-ship, there’s no power for anything until you charge up,” says Phil Lee with Octoplex. While digital-switching systems can deliver real-time metrics for battery health and power draw, owners are wise not to push this envelope too far.