An unfamiliar dock, a crosswind, some current and a bevy onlookers. Sound stressful?

Raymarine‘s DockSense assisted-docking technology is poised to reduce this headache—significantly—using sensors, machine vision and deep machine learning to constantly define and defend a “virtual bumper” around the boat.

I got my first look at the technology on Florida’s Lake X, the fabled (and secretive) former test ground for Mercury Marine’s outboard engines. An 8-knot breeze blew as Matthew Derginer, Mercury Marine’s vessel software and controls engineer, used a joystick to control a Boston Whaler 330 Outrage’s dual Mercury Verado outboards. He nudged the boat’s stern toward a slip at an intentionally steep angle.

But instead of the stomach-churning crunch of fiberglass hastily greeting concrete, we heard the happy hum of a docking boat. Mercury’s Advanced Pilot Assist system and Raymarine’s DockSense technology worked in tandem to keep the boat exactly 3 feet from the dock, allowing Derginer to pilot the boat into position easily.

DockSense makes docking a matter of pingponging into the berth by using the virtual bumper, or by carefully threading in using a multifunction device. Regardless of one’s angle of approach or docking style, the virtual bumper won’t let the yacht inadvertently contact the dock. Once the yacht is properly aligned, the yachtsman disengages the virtual bumper and makes fast the dock lines.

“At its core, DockSense is the virtual bumper,” says Jim McGowan, Raymarine’s Americas marketing manager, adding that the virtual bumper also can be used to push the yacht off the dock.

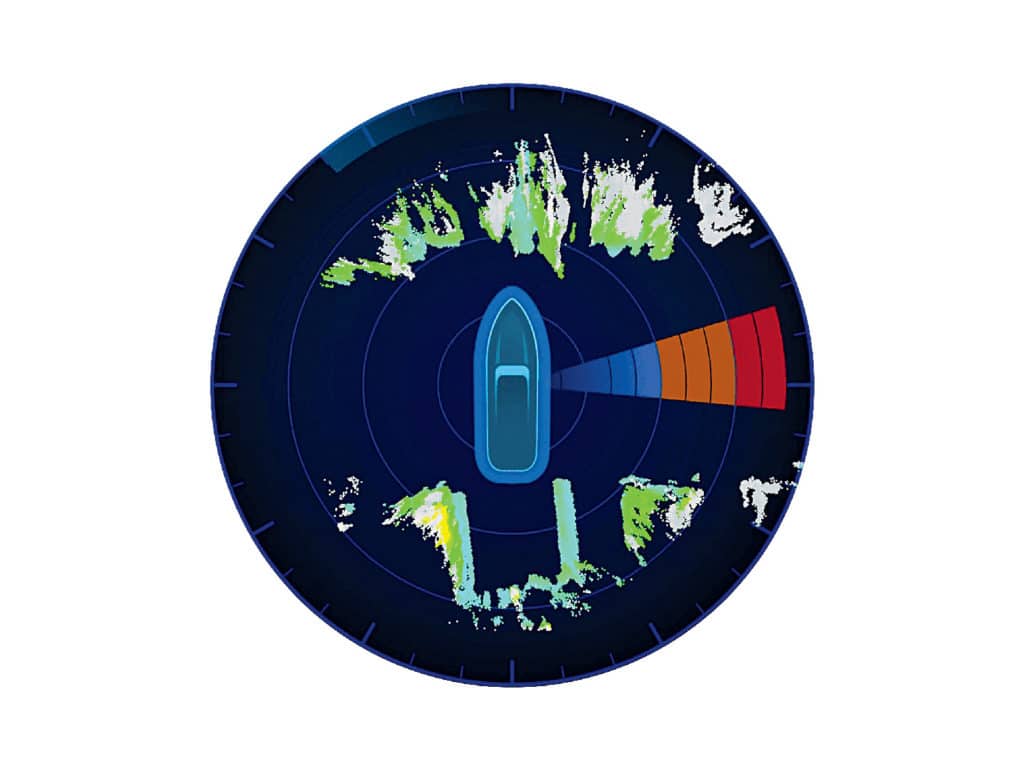

DockSense uses stereo cameras to create a real-time, nearly 540-square-foot map of the surrounding waters and the yacht’s engines. “Users define a safety zone around the yacht, and DockSense uses cameras to enforce this zone and command the boat’s engines to keep everything out,” McGowan says. “It’s smooth and controlled all the time.”

Eventually, McGowan says, users will be able to select a preferred bumper range (from 0 inches to 10 feet) and the system’s authority level (read: throttle ceiling). For now, Raymarine and its parent company, FLIR, partnered with the Brunswick Boat Group (owner of Boston Whaler and Mercury) and Groupe Beneteau (owner of Prestige Yachts) to create two similar, sensor-based, docking-assist setups for two very different propulsion systems.

While both projects are in the developmental stage, hardwarewise, they work the same way. DockSense creates the map and virtual bumper using a Raymarine Axiom MFD running a DockSense app; a compatible joystick control and engine system; a black-box DockSense processor; five FLIR-built, Raymarine-marinized stereo cameras with built-in attitude and heading reference systems (AHRS); and a separate Raymarine AHRS and GPS module. The system’s stereo cameras, which have two lenses, count, measure and recognize objects in three dimensions from mounts on the yacht’s hardtop. Each camera delivers a range of 30 feet, and collectively, the cameras deliver 360-degree video coverage. The AHRS and GPS module is also hardtop-mounted, however, McGowan says that these sensors will likely be hidden once the system, which will only be available on the new-boat market for the foreseeable future, enters production.

Reportedly, the cameras are capable of deep machine learning. “The cameras are shipped with a base knowledge, and they will learn over time,” McGowan says.

These capabilities should allow the stereo cameras to deliver “machine vision,” which means using video analysis and inspection to control or guide things automatically.

“Machine vision lets the camera perceive depth and make judgments in 3D,” says Jim Hands, Raymarine’s marketing director. DockSense uses machine vision to scan constantly through each camera’s range for nonwater objects, and it works with the yacht’s engines to ensure that nothing enters its virtual bumper.

DockSense’s cameras deliver AHRS data and imagery feeds to a black-box processor, which also receives input from the separate AHRS and GPS module. This combination allows the processor to remove vessel roll, pitch and yaw from its map and—using GPS—to determine the vessel’s position and speed.

The system also displays an icon of the yacht with a color-coded map of its surrounding area (picture a radarscope) on a Raymarine Axiom MFD with the DockSense app. The colors indicate how high objects are off the water’s surface, and whether the camera is imaging the objects in real time or as previously mapped data points.

To date, DockSense has been fitted aboard two demonstration yachts: the Boston Whaler 330 Outrage and a Prestige 460 with joystick-controllable pod drives. While both installations’ sensors are similar, their control interfaces differ significantly.

“With inboards, DockSense talks directly to the engines,” McGowan says, “but with outboards, DockSense is talking to Mercury’s advanced piloting-assist system,” which in turn talks to the engines.

“Joystick controls can do a lot of interesting and advanced maneuvers,” McGowan says, “but I don’t see any reason why DockSense couldn’t be applied to a wheel, so long as there’s an electric connection to the steering gear. Same with the yacht’s engine controls—they need to be digital.”

Yachts running DockSense also need to have multiple engines or pods to enforce the system’s virtual bumper, although Raymarine’s team envisions incorporating thrusters.

Hands and McGowan also imagine a future in which DockSense processors draw upon multiple onboard sensors to render maps. These sensors could include AIS, lidar, radar, sonar, thermal-imaging cameras and aerial feeds (see “Drone Vision” at left), plus the ability to read vector cartography.

“We want to feed DockSense with as many sensors and as much knowledge as possible,” McGowan says.

Depending on what sensors and capabilities are eventually added, DockSense could someday be used as collision-avoidance technology. For now, it’s newsworthy that the technology works, as I experienced firsthand in ideal conditions with flat water, a thin breeze, sunny skies, and no traffic, current or tide. Those conditions, of course, beg questions about how DockSense handles tougher situations and highlight the need for users to maintain their docking skills, perchance an ill-timed problem unfurls.

But, so long as boaters approach Raymarine’s DockSense as an assistant, there’s little question that the technology will positively disrupt the often dark and usually stressful art of docking.