The boat’s port quarter lifted as a crunching, nails-on-a-blackboard screech vibrated through the hull, jarring me from the haze of the monotonous night run. My eyes locked onto the depth sounder while my brain processed the information.

Four hundred and thirty-three feet.

I exhaled slightly. We were still moving forward.

The respite was short-lived. The shaft sounded like it was going to drive through the hull and plop itself on the settee. Whatever we hit had dragged along the bottom and smacked the port propeller. It was wasted.

I shut down the port engine and wallowed at a reduced speed under the molasses sky off Eleuthera Point in the Bahamas. I was off the beaten path, where service is scarce and towing is nonexistent.

This type of cruising requires a good measure of self-sufficiency. In addition to having a well-equipped spare parts chest and good mechanical skills, skippers must know how to change a propeller underwater. This skill-when a yard is hundreds of miles away, can’t handle a boat your size or is deserted on a Sunday afternoon-can save your cruise. Regardless of the size of your boat and propeller, the key to making an emergency underwater prop change is having the proper tools for the job and knowing how to use them.

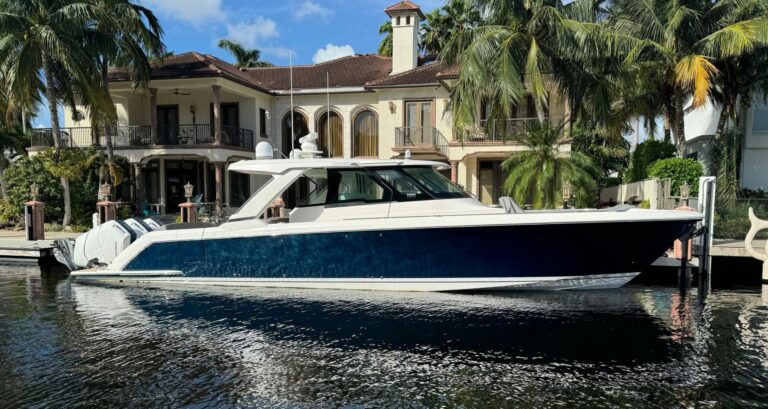

After assessing my situation that night, I realized we had almost everything we needed to make a fix: properly sized wrenches, a spare set of props and a prop puller. What we were missing on our twin-screw Grand Banks 49 was appropriate dive gear (“Power Play,). Luckily, we were able to borrow some from a neighboring boat.

Our remaining functioning prop would get us the 80 miles from Eleuthera Point to George Town in the southern Exumas. While our boat would be too heavy for the local yard to pull on its travel lift when we arrived, I reasoned that the area offered the most promising prospect of protected waters for a prop change and for repairs, should they be necessary.

Fortunately, our boat’s owner had a spare set of propellers on board. This is one of the most overlooked necessities for boats that cruise outside local waters. Spare props are worth every penny. Once you have them on board, make sure they are crated or secured and can be stowed low in the hull, to keep weight properly distributed.

We geared up and headed underwater with our tools, including a wrench sized to fit the hub of our propeller, with an arm long enough to provide needed torque underwater. For us, this repair was a two-man job; one guy held the prop with a piece of wood between the blades while the other cranked down on the wrench.

Our prop came off with minimum effort, but this isn’t always the case. Having a prop puller aboard, while not mandatory, will make any repair far easier, especially underwater. Pullers are designed to apply a high amount of pressure without the use of a sledgehammer and wood wedges, which is almost impossible underwater anyway. It works like a parallel clamp, applying pressure to the back of the hub and pulling the prop forward on the shaft. A puller also reduces the risk of damaging the shaft, jolting the bearings, or damaging or marking the wheel itself. Depending on the size of your wheels, a puller will cost $150 to $400, money well spent. Your local prop shop is a good source.

If you find yourself without a spare prop aboard and in an emergency, you can bang out and fix any dings manually. This is a crude and temporary solution I’ve had to employ on a few occasions, but it allowed me to run at reduced rpm until I could get to a yard stocked with the right equipment.