The passage from Seattle to San Diego was billed as a milk run, but that was before Michael Pack and his crew aboard Caelestis, Pack’s Wauquiez 47, suffered a crash jibe in gale-force winds that shattered their traveler, ending their ability to maneuver easily. By dawn, the wind had lain down to 35 knots, but the seas were still running 15 to 20 feet, and a failed generator made it impossible to run radar in the light fog some 110 miles off San Francisco. Fortunately, Caelestis’ Vesper Marine AIS WatchMate draws only 3 watts, so it was still powered on to warn Pack that Caelestis would pass within 0.1 mile of an outbound container ship roughly 15 to 20 miles away — a serious danger given the busted traveler, the wind and seas, and the container ship’s turning radius of 6 degrees per minute (which the AIS displayed). Rather than panic, Pack called the vessel directly and asked the captain to come to starboard a few degrees, an unusual request that was honored.

“We wouldn’t have even known he was there without AIS,” said Pack, who had fitted his AIS a week before leaving Seattle. “You can’t write the check on the way down.”

At its core, the Automatic Identification System (AIS) provides vessels both mighty and modest with the ability to “see,” automatically, nearby traffic while broadcasting their own signals to avoid collisions, but it’s also evolving into a vital navigational tool with the advent of the U.S. Coast Guard’s e-Navigation initiatives.

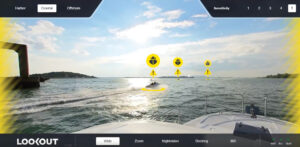

Hardwarewise, AIS units typically consist of a VHF transmitter, two VHF receivers, one Digital Selective Calling-enabled VHF receiver and an internal GPS receiver. System and vessel depending, AIS units broadcast every two to 30 seconds while constantly “listening” for incoming signals. Received transmissions are displayed as “targets,” both on minimal keyboard displays and on AIS-enabled monitors, radars or electronic-chart display systems. By selecting an on-screen target, an AIS user instantly obtains critical navigation information including the target’s name and type, position, course, speed and other status reports (e.g., underway, anchored, restricted in ability to maneuver). Provided that each AIS-equipped vessel has obtained and programmed its nine-digit Maritime Mobile Service Identity number (a unique number registered to each vessel), nearby users can “knowingly” hail one another via VHF.

There are two classes of AIS mobile units: Class A and Class B. Class A AIS is mandated safety equipment aboard all SOLAS-class (Safety of Life at Sea) ships, and in the United States almost all self-propelled commercial vessels 65 feet and larger are also required to carry it. Class B AIS was designed for recreational vessels, and while it’s not as powerful as Class A, it provides nonregulated vessels with an important safety layer. Additionally, “listen-only” AIS scanners are available.

All transmitting AIS units use unique channel-access methods that allow myriad users to share finite channel access efficiently, but that favor Class A over Class B signals. Class A transmits at 12 watts, while Class B transmits at 2 watts; this gives Class A units a greater operating range but otherwise doesn’t make a difference. Furthermore, Class A units are ensured a transmission slot every two to 10 seconds, depending on the vessel’s speed (faster speeds require faster refresh rates), while Class B units transmit every 30 seconds. This last point is especially germane for faster vessels, because separations between position reports can cause a yacht to outpace its displayed AIS target, spiking anxiety for other vessels, especially in crossing situations. Owners of quick rides should consider that Class A AIS provides the shortest position intervals (this becomes more important as the vessel’s speed exceeds 20 knots); however, Class A units require that operators manually enter information upon arrival and departure from each port of call.

Broadcast AIS signals can be “heard” not only by nearby vessels and aircraft but also by shore-based facilities, such as the Coast Guard’s Nationwide AIS (NAIS) base stations, allowing the Coast Guard to monitor maritime traffic and use AIS as a vessel traffic tool. Since AIS uses line-of-sight VHF communications, range is typically limited to 10 to 20 miles, with masthead antennas delivering better performance than obstructed antennas; also, shore-based repeater stations can substantially extend this range. While an AIS unit’s range is limited, it offers better propagation than radar, allowing AIS signals to “peer around” low-slung islands and making this technology ideally suited for soundings festooned with small landmasses.

“We see an annual increase of 10 to 15 percent in the number of Class B users in Sweden, but it’s not growing as quickly in other places,” said Anders Bergström, the owner of True Heading, who reported that 10 percent of all sailboats over 25 feet are AIS-equipped in Sweden, while only 4 to 5 percent of the nation’s powerboat fleet carries this equipment. “The original, anti-collision [application] is the most important, especially in the fog and darkness, but other aspects [are also beneficial] — it’s fun to see the traffic, much like plane-spotting apps.”

Some manufacturers embed Wi-Fi into their AIS units, allowing them to share data wirelessly. “Independent of other navigation equipment, it’s handy to have AIS data on your smartphone or tablet,” said Jeff Robbins, the co-founder of Vesper Marine, who explained that Vesper’s Wi-Fi-enabled AIS transponders include a high-speed GPS unit and an NMEA 2000 gateway, allowing these units to broadcast instrumentation data. “Some people use [their tablet/smartphone] as their primary navigation tool, while others just want to use [it] as a repeater.”

Irrespective of your preferred equipment, the decision to add either Class A or Class B AIS comes down to your yacht, your cruising grounds (e.g., prominence of fog, islands and heavy metal) and — with the Coast Guard’s evolving e-Navigation initiatives — your information appetite. “AIS is currently the only tool to transfer digital data onto your electronic-nautical chart,” said Jorge Arroyo, a Coast Guard program analyst who has been instrumental in writing AIS regulations and standards, referring to the application specific messages (ASMs) that the Coast Guard can broadcast via AIS. “The ASM is the envelope. Within the envelope [the Coast Guard] is free to transmit all the other navigation-specific information that we wish. … It’s our way of providing digital navigational data directly to the vessel.”

Given that AIS increases situational awareness for all mariners, all boaters would be well advised to include this equipment on their helm or nav station, and to become familiar with emerging AIS search-and-rescue technologies, as well as with the U.S. Coast Guard’s new e-Navigation initiatives.