Perfnov08525.jpg

The most important hole in the hull of an inboard boat is the critical point where the propeller shaft goes through the bottom. The mechanisms for supporting the shaft at this point-and keeping the water out-vary widely in design, cost and maintenance requirements. Traditionally, the job was accomplished with a stuffing box, also called a packing gland, but proprietary sealing systems have taken the lead in recent years.

It seems everyone loves seals. Builders love them because they’re easier to install and align. Owners and captains love them because they don’t leak and don’t require as much routine maintenance. And repair yards love them because, in spite of their general reliability, there’s a small percentage that fail catastrophically, generating substantial repair bills.

This failure is almost always due to a loss of cooling/ lubricating water, necessary for sealing systems and stuffing boxes alike. Whether provided from outside the boat through the shaft log or through a tap from the engine’s cooling water system, it is vital to maintain a continual flow of water, and this is an important point that should be added to every maintenance checklist. When the water flow stops or is interrupted, packing can scorch, seals can melt and fail, and seal or packing carriers can sometimes seize to the shaft, resulting in rupture of the assembly. And if not detected, the engineroom can flood, possibly sinking the vessel.

In light of the disadvantages of a traditional stuffing box, the appeal of proprietary sealing systems has become obvious. Some use a face seal and some a lip seal, but they share the advantages of being virtually leak-free and requiring little or no routine maintenance, explaining their popularity with owners. They all use a flexible hose or bellows to make installation quick and easy, usually to a simple piece of tubing through the hull bottom, explaining their popularity with builders. The hose or bellows also allows for a bit of misalignment between the tube and the seal assembly, and helps keep vibration and noise transfer to a minimum.

Face seals, such as the PSS by PYI, bear against a contact face, which is a split ring that bolts around the propeller shaft and rotates with it, just ahead of the seal. It depends on the pre-compressed bellows to maintain a slight pressure, assuring just the right degree of contact between the seal and the rotating face. Too little and it will leak, too much and there will be unnecessary wear.

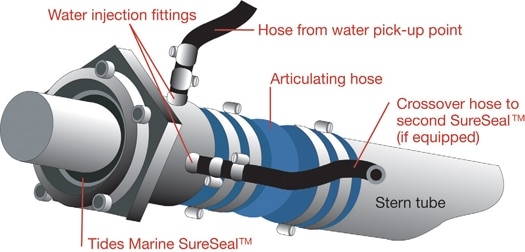

Lip seals, such as Tides Marine’s SureSeal, have no rotating ring. The seal, instead, is directly against the propeller shaft. SureSeal uses a bellows, similar in appearance to that used for PSS, but it is simply to allow for flexibility, not to maintain seal contact.

So, what’s best? Lip seals require no rotating ring, and in fact, have no moving parts at all, but they depend on a pristine propeller shaft surface to maintain a seal. Polishing of the shaft may be required before installation, and any corrosion, nicks or pits can compromise the seal, allowing leakage and premature wear to the seal itself. Face seals require a rotating ring and adjustment of the bellows preload, but because of O-rings within the ring, they can be mounted to less-than-perfect shafts and still maintain a good seal. A disadvantage shared by both is the need to uncouple and withdraw the shaft for seal replacement, sometimes necessitating hauling the boat. This expense can be delayed, at least once, by mounting a spare seal in a carrier on the shaft itself at the time of the original installation.

And don’t count out stuffing boxes. Though they require routine maintenance and leak a bit, they’re simple to fix and don’t normally require the boat to be hauled for repacking. That’s why they’re still preferred by some owners of long-range cruising yachts and by many commercial vessel operators.

| Logs and Fishes? ******Fiberglass yacht owners sometimes need to have faith.**In preparing this column, I spoke to repair personnel in boatyards from Cable Marine (primarily production yachts in Florida) to Knight & Carver (bigger yachts in California) to Colonna Yachts (megayachts in Virginia), and to experienced designers from Setzer Design to Donald L. Blount and Associates. The anecdotes and experience have been distilled into the advice in this column, but Ward Setzer shared one additional concern that troubles him.In production fiberglass boats, the shaft log is often molded into the hull bottom, but for custom built and production designs where different engine and gear combinations are offered, and even for some production yachts, the building process can be a little different. After setting the engine and shaft strut, a hole is cut in the finished hull bottom between the two, and the propeller shaft and a fiberglass tube are slid into place. Once the shaft is coupled to the engine, the fiberglass tube, which will hold the shaft seal assembly, is roughly aligned and glassed into place. The problem comes on the upper side of the tube outside the hull and the lower side of the tube inside the hull. Because of the shallow angle at which the tube penetrates the hull, it is difficult to do the glasswork required at these two points (this is not a dilemma with custom steel or aluminum boats, where a full penetration weld from one side solves the problem). The result can be a little sloppy, so some builders cover it up with a putty of resin and chopped glass fibers and paint over it, a cosmetic fix that Setzer refers to as “fillets and faith.” Though it works fine in most cases, it’s a spot of potential failure, so when doing your regular checks on your stuffing box or shaft seal, take a look at the point where the shaft tube goes through the hull, too. If you see any evidence of cracking, it would be wise to have your boatyard or a surveyor check it out. |