My dad purchased Southern Cross, his modified j/44, in late 2001. While she nicely ticked all of our offshore sailing wants, her electronics were dated. Also, being that it was 2001, the electronics consisted (mostly) of discrete instruments. There was little networking or interoperability. This problem was short-lived, however, because my dad installed a then state-of-the-art NMEA 0183 data backbone, allowing us to pipe networked information to our PC-based navigation software.

This system has worked well for countless offshore miles, but its late-1990s architecture didn’t foresee advances such as wireless devices, ubiquitous connectivity or the Internet of Things. Fortunately, the National Marine Electronics Association’s soon-to-be published OneNet protocol addresses these shortcomings and more while aiming to future-proof early adopters against technology’s ever-quickening drumbeat.

OneNet began in 2010, when a group of marine-electronics brand managers asked the NMEA to establish a standardized protocol for transmitting and receiving NMEA 2000 messages over Ethernet. Individual brands had already been networking multifunction displays with radar using Ethernet, but customers had to stay within a particular manufacturer’s walled product garden — Apple style — to enjoy this connectivity.

The recently published OneNet standard, says Steve Spitzer, NMEA’s director of standards, will live in parallel with NMEA 0183 or N2K backbones and will use the same NMEA network message database as N2K, allowing OneNet to share information with other networked instruments or devices in a common format that supports interoperability.

“I can’t overemphasize OneNet’s security,” Spitzer says. “It’s not personal data, but [the boat’s] actual navigation and operations that could be hacked.”

One way to prevent electronic tomfoolery, of course, is to firewall the network. OneNet accomplishes this in a process similar to that of a smartphone pairing with a Bluetooth-enabled speaker.

“OneNet owners can secure the network so that nothing [but NMEA-certified devices] can get on, or they can open it up to a non-NMEA-certified device,” Spitzer says.

In all cases, the network’s owner has final say about all devices or software that try to join the network. “For commodity devices such as smartphones or tablets, we don’t expect the iPad to be OneNet-certified, but the application that it’s running needs to be certified,” Spitzer says. As an additional security measure, all outgoing OneNet messages are encrypted before being shared; once they are received, other networked devices authenticate each message before unlocking it.

In addition to bolstered security, OneNet’s data backbone delivers 5G data-transfer speeds of 100 megabits per second to 10 gigabits per second, as much as 40,000 times faster than N2K’s data-transfer speed of 250 kilobits per second. OneNet also provides up to 25.5 watts of power over Ethernet to all connected instruments. And while N2K networks support as many as 52 devices, OneNet can support a virtually unlimited number of instruments, multifunction displays and wireless devices.

OneNet’s most forward-leaning attribute is its IPv6 architecture, which is the most recent protocol for internet traffic. “There are no more IPv4 addresses available for North America,” Spitzer says. “Does a boat need endless IP addresses? No. But it’s the connectivity that we wanted.”

Additionally, OneNet is designed to evolve and adapt as fiber-optic cables and next-generation connectors become available, and as Ethernet-based applications evolve.

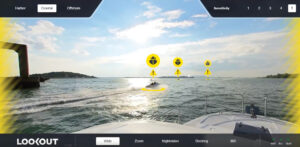

Today, OneNet allows users to send high-bandwidth data, such as engine-room camera feeds, over the network.

“A Maersk container ship might generate 1 terabyte of data a month,” Spitzer says. “I don’t see most recreational boats generating this much data. It’s hard to know where [technology] will go, but I believe OneNet will provide the necessary scalability.”

OneNet was undergoing final tests at the time of this writing, so there are no yachts equipped with the system and no OneNet-certified aftermarket devices available yet. Adoption, Spitzer says, “will start with people who want the latest and greatest. I suspect the retrofit market will be the first market, then new builds.”

Hardwarewise, owners will need to install at least one Ethernet switch that supports OneNet network services and OneNet-certified devices, the latter of which Spitzer hopes will be available by 2020. There’s often significant latency from the time a protocol is published until it reaches maturity. Spitzer notes that N2K was published in 2001 but only transitioned out of its early-adopter stage in 2017.

“Even when OneNet is published, there will be some development cycle,” Spitzer says. “It might be faster than N2K because Ethernet is more ubiquitous.”

In the meantime, OneNet offers significantly improved automatic network-configuration capabilities and multicast routing, as well as the ability to interact with other connected smart devices by way of cellular, Wi-Fi or satellite-communications signals.

“A cruiser could turn the lights on and off at his home while he’s in Barbados on his boat, and he could look at his [home] security cameras, all through his boat’s satellite-communications system,” Spitzer says.

So, if you’re a yacht owner contemplating a new-yacht build or a refit, OneNet could be a wise investment, especially if you envision cruises amid the future’s constantly unfurling technologies.