Need to Know

I recently toured a new 65-foot vessel with electronics that would impress most any skipper. There were no less than three 12-inch Garmin touchscreens in the pilothouse offering 2- and 3-D chart plotting—including HD radar overlay— all synchronized by fast, precise heading and position data coming from a Furuno satellite compass perched like a flying saucer on the antenna mast. But I got an uneasy feeling on behalf of the owner, and owners to come, because there were hints that the installation had not taken full advantage of NMEA 2000, the multi-manufacturer sensor networking standard that I’ve learned to love for its reliability, dexterity, and ability to grow.

One of several tipoffs: The satellite compass was Furuno’s model SC50 rather than its newer SC30. Both have excellent specs, but the former outputs data in the older NMEA 0183 format, while the latter uses 2000. The 0183 protocol works, but 2000 is much better, as I’ll attempt to explain. Now, this particular oversight may have happened because the electronics should have been selected later in the build process, but I suspect other factors. Many electronics installers and boatbuilders would rather do things the old way, if they can get away with it, and there’s even some ill will toward NMEA 2000 within the industry, and among some boaters. It’s largely based on misunderstandings and exaggerations, all the more reason why a skipper who may never mess with the cables behind the screens ought to understand the benefits N2K, as it’s nicknamed, can deliver.

If an SC30 satellite compass had been used on that vessel, for instance, a rugged cable designed to shield its contents from EMI (electromagnetic interference) would have carried both data and 12-volt power between the mast and the pilothouse. At the top of the mast, a standard waterproof female connector would have been screwed onto the SC30, and a male connector at the other end would have led into an N2K backbone along which were connected via cable tees up to 50 drops networking other sensors, devices, and displays like the Garmins, plus a single power feed sufficient for at least the sensors. By contrast, NMEA 0183 includes no connector standard, let alone a combined power and data cable. So the SC50 had two cables run to it, both somewhat delicate because the wires involved are quite thin, and the one bearing data ending at a terminal block or a permanent splice.

The NMEA 0183 protocol also limits device connections to one data “talker” and a few “listeners,” each requiring a separate wire pair. To send SC50 heading info to the autopilot (AP) would necessitate a second delicate connection, sending Garmin multifunction display (MFD) “go to” commands to the AP via another connection, and so forth. But since N2K is a true multi-talker, multi-listener protocol, that single hypothetical SC30 connection would have delivered heading and position info to the MFDs, the AP, and any other interested device along the backbone, which would also provide communications between the MFDs and AP and so on. Incidentally, larger data feeds—like radar, sonar, and multiple MFDs—generally network via Ethernet, though the various marine brands do not use it for sharing such data.

NMEA 2000 is meant to “plug and play” easily, and even across brands. Installing, say, an Airmar or Maretron ultrasonic wind sensor next to the satellite compass would take just a couple of short cables and a tee, for example, not more cable runs down the mast. And the same is true at the helm for adding, say, one or more of the many NMEA 2000 instrument displays that can show wind speed/direction, heading, and many other standard N2K messages that might be coursing through the backbone. I’ve mixed and matched a great many sensors and displays over the last few years, and have seen an impressive degree of hard- and software compatibility.

In fact, NMEA 2000 was conceived as a stricter standard than 0183, and it includes a rigorous certification process the older, less powerful protocol lacks. But there’s still room for creativity. Any device is allowed to transmit a certain percentage of proprietary messages. The SC30 is again a good example, able as it is to measure not only a vessel’s pitch and roll but also its “heave,” the up and down motion created by seas it passes over. That unusual value is not yet included in the N2K standard, but Furuno created a custom message that certain of its fishfinders can use to subtract heave from bottom imagery. I could go on for pages about all the other integration niceties that NMEA 2000 has created or is hosting.

During N2K testing, I haven’t had the EMI issues that sometimes cause strange behavior aboard. I once delivered a fast trawler on which making toast caused the autopilot to change course, a startling problem eventually attributed to the effect of inverter EMI on a poorly shielded 0183 cable running from the electronic compass.

So, with nearly every manufacturer putting NMEA 2000 interfaces into most of their electronics, why are boats coming down the line that hardly use it? The transition has been slow to reach some categories, like VHF radios and AIS transponders, and all the MFDs that support NMEA 2000 also support 0183, so they’re compatible with those devices and older gear already on a boat. Thus an installer who prefers the familiar can stick with it, even if it takes longer and the results are less robust and less conducive to future changes. Plus, to be frank, some of the very companies which, as NMEA members, helped create N2K also confused the boating public by trying to brand it as their own.

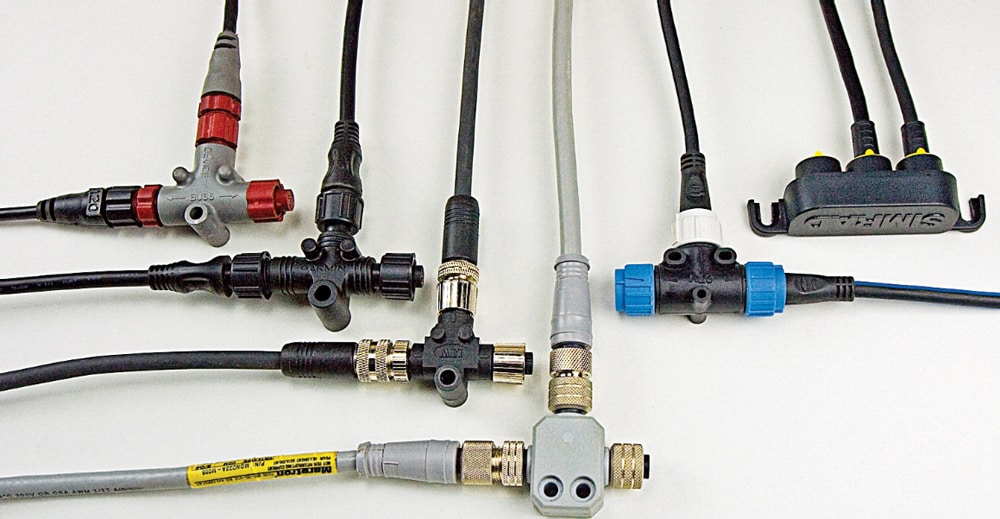

Both Simrad and Raymarine, for instance, designed their own N2K-like cable and connector systems, called SimNet and SeaTalkNG, respectively, usually with “NMEA 2000 compatible” asterisks. They each have certain slight features the standard cabling system doesn’t and it turned out that adaptor cables make it easy to marry them to other manufacturers’ equipment, or to marry their gear to standard backbones. Nonetheless a standard plugand- play network that doesn’t always actually plug together understandably fueled the skepticism of boaters who weren’t sure the manufacturers wanted to share data.

Some boaters also overanticipated the extent of N2K plug and play, and were disappointed. The calibration of sensors, for example, generally doesn’t yet work between brands. If you want to correct the offset of a wind vane that wasn’t mounted exactly right, you may need that brand’s display to do it (though corrected data is seen across the network). And if the manufacturer of an all-in-one instrument display improves its software—a regular occurrence since new N2K messages and abilities are still being created (and software bugs happen)—you’ll need that manufacturer’s MFD with its card slot, or its PC software, to do the update instead of sending in the device.

While N2K is not perfect, and may never be, it’s great for networking short, critical data messages around a boat. It also scales well and lends itself to some pretty fancy big-yacht integration. One thing’s for sure: If your installer, or the normally well-informed skipper down the dock, pooh-poohs NMEA 2000, get a second opinion.