Capt. Paul Mann couldn’t take my call — because he was unloading a delivery truck. That and prioritizing a customer’s build schedule are uncommon tasks for the head of a custom yacht-building company, and they offer tremendous insight into the kind of boatbuilding shop Mann runs. He is just as involved in every hull that leaves his shop today as he was some 30 years ago when, at age 25, he built his first boat. “All I wanted to do back then was run fishing charters,” Mann says, “so I built a boat. But then someone else wanted one. And then someone else again. For 16 years, I ran charters, often working seven days a week, while during the offseason I would build boats … but at some point, the boatbuilding time started spilling into the fishing time. Something had to give.” As much as he loved fishing, he grew to love the building and design process, of taking a stack of wood and turning it into a custom-crafted keepsake. He moved on from single-screw charter boats to sport-fishing yachts, with a fleet today that ranges from 52 to 81 feet length overall from his shop in Manns Harbor, North Carolina, between Albemarle and Pamlico sounds.

“Custom boatbuilding is the best form of art you can do without being what most people would call an artist or an architect,” he says. “I was lucky in that I was born in a time when we didn’t have specialists. Back then, you had one doctor who you saw for most anything, not like today when you have a different specialist for every issue. It was the same way when it came to building boats. So early on, I worked on every aspect of the process. I learned how to work the wood, but I also learned how to align a shaft. Today, we have different specialists on our team, and unlike other forms of art, building a custom boat is a team process.”

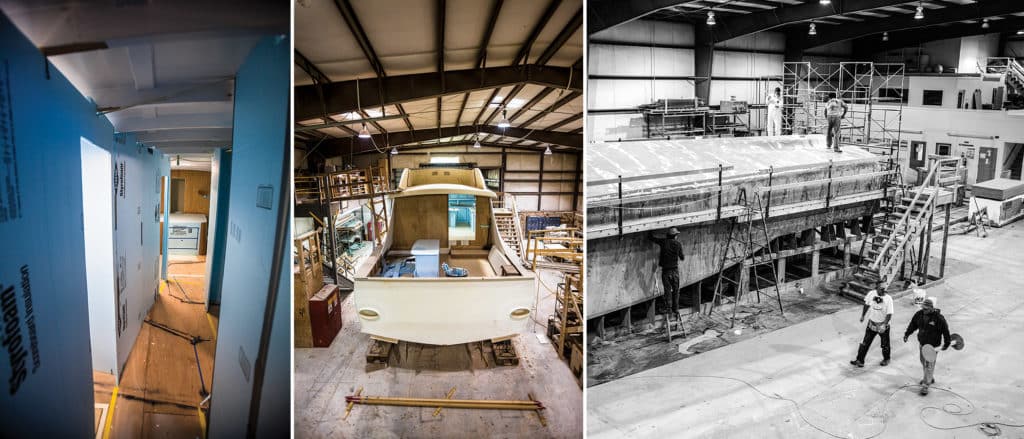

Mann gives much of the credit for his success to that team, saying, “I have to take my hat off to the quality of my employees. We have between 30 and 35 at any given time, working on two or three boats at once in our 40,000-square-foot building.”

Most of the people working at Paul Mann Custom Boats have been there for years, many for decades. He says they add to the input from each yacht’s owner, which also is invaluable.

“The owner is a big part of the process, as is the owner’s crew, which is often as knowledgeable as anyone,” Mann says. “Actually, you’re all sort of married for the duration of the build. We’re in contact throughout the process, and we video the project as it takes place. The owners give us feedback, let us know when they’ve changed their minds about something or they see a way to make an improvement, and we keep them constantly informed. They feel a sense of creation along with the rest of the team because they play a very real role in it.”

Mann loves the input and says he still learns new things by interacting with different people on each and every build.

“As life changes, boat styles change,” Mann says, “and someone who’s interested in fishing with the guys at one point in his life may decide he wants a boat that the whole family can go out on, later in life.”

One owner had Mann design a 77-footer that could sleep 12 people so all his kids and the kids’ kids could stay aboard. Another owner started by having Mann build him a 52-footer, then later a 60-footer, then years after that a 56-footer.

Finding success with such an array of boats, and with custom Carolina sport-fishing yachts in general, he says, was something of a surprise.

“We designed and built our plank-on-frame boats specifically for fishing the waters out of Oregon Inlet,” he says of the waterway on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. “We had to be able to fish when it was rough, and we wanted to come home at the end of the day. So we were just building to our needs. We didn’t realize that our boats were superior for handling rough seas compared to many of the boats built elsewhere until they started traveling around more. When Carolina boats began going to Florida and people there saw how our boats performed, it became something of a big deal.”

Around 2000, a change in Carolina design and construction took place with the exploding popularity of jig-built boats: cold-molded boats built over multiple frames, usually CAD-designed and router-cut to create a “jig” around which the hull is constructed. Mann says he still prefers traditional plank-on-frame construction, but he will build on a jig if that’s the customer’s desire.

Paul Mann Hull No. 37: Meet Jichi

“The boats are strong and seaworthy either way,” Mann says. “I just personally prefer plank-on-frame boats, and I can build them lighter than a jig boat, using fir stringers and okoume in the sides and bottom. There’s not a right or a wrong; they’re just different, and the market demanded jig construction. I’m not so hard-headed that I can’t change, so I carried my designs to an architect, put them on a computer and started routering jigs — but they’re still my designs.”

Today, Mann takes breaks to enjoy fishing and wing shooting, but his ambition to build great boats remains. “I’m 58 now and hope to be doing this until I’m 70,” he says.

And if you get asked to wait for a moment after calling Mann, sit tight; he’ll be done unloading that truck before you know it.

Tournament Proven

Paul Mann’s vessels win tournaments. In 2017, the 57-foot Naira won the Presidential Aruba Caribbean Cup; the 56-foot Qualifier was top boat at the Virginia Beach Billfish Tournament; and the 58-foot Lo Que Sea won the 54th annual Buccaneer’s Cup Sailfish Release Tournament.

Award-winning Woodwork

Paul Mann’s boats are known for performance, fishability and first-rate interiors. His shop’s technical woodworking skills in creating the teak veneer on board the 60-foot Caught Up earned honors in the cabinetry category of the 12th annual Veneer Tech Craftsman’s Challenge.

Mann Memory

In 2003, I was at the helm of the 65-foot Paul Mann Poor Girl off Virginia Beach, doing 35 knots in a steep chop. Her owners were next to me, and Mann was behind me. I looked at him and asked, “Want me to pull back?” Arms crossed, he said, “Put the throttles down. She’ll eat this up all day long.” And she did too. — Patrick Sciacca