yachting/images/magazine/2007/052007/yl_destinations1_550x305.jpg

I must have fallen asleep, because I came to sprawled in the sand under the coconut palms, the tide advancing up the beach with Saed, my Maldivian butler, peering solicitously at me. Late afternoon storm clouds were building on the horizon, and tuna chased skipjack across the velvet evening waters where Rania lay at anchor. “Water”, I gasped, then remembering my manners, added “please”.

“Not the usual champagne, Miss Lisa?” the handsome, wiry Maldivian teased. “We have been chilling a bottle and dinner will be served soon, in the place you requested.

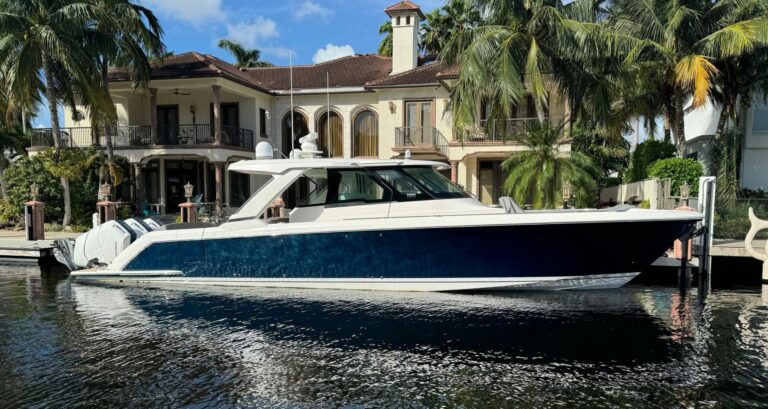

Two days earlier I had been stranded on this tiny gem of an island with two friends, John and Michelle, at what has been called the most expensive resort in the world. Well, not exactly stranded: For there was Rania, an 86-foot GulfCraft Majesty yacht, easily cruisable at 25 knots, and her sistership, Cleopatra. Along with their crews, both were at my beck and call-each offering three staterooms, Jacuzzi, fighting chairs for sportfishing, and all the water toys I could ever use. Oh, if I’d wished to hop to Male for dinner, a seaplane was available.

Of course, if I’d preferred to stay ashore, there were six suites furnished with a hip elegance, large flat-screen TVs, and indoor/outdoor 500-square-foot bathing gardens (to call them bathrooms would be an injustice) that were spas unto themselves. There was an entertainment lounge and programmed iPods; the air-conditioned gym’s glass walls had views of purple Maldivian sunsets. For reading or dining there were overwater pavilions at the ends of what seemed like long docks to nowhere, silk sheaths of purples and oranges fluttering invitingly from their rafters in the light sea breezes. A bar stood at one end of the island, where Tony concocted martinis, Bellinis or anything else.

Also at my disposition were two butlers, two chefs, two massage therapists, two dive masters and more than 25 other staff, and the women from the neighboring island who arrived each morning to sweep the beaches clean of the slightest stick, including leaf or footprint.

For this, I would consider my $12,000 a night well spent. Yet for an additional $750 per person a night, I could have brought along 11 more friends. “We usually have no shortage of guests, manager Vijai Singh said. “There are more than 200,000 multimillionaires in this region and the Middle East accounts for $1 trillion of the $30.8 trillion of the world’s highest net worth.

After three days of deciding what to do each day-where and when I would like to have afternoon cocktails and whether I would prefer a two-hour Thai or Ayurvedic massage-I felt weary. So that afternoon I had laid out a towel in the perfect sand, with nothing on the horizon but Rania and a dozen shades of blue water. As I dozed, I imagined myself at the island’s beginning, thousands of years ago when ridges of undersea volcanoes were forming. Coral finished the job, growing up over the centuries, breaking the surface while gathering sand, forming thousands of atolls. Within the atolls, protected from the breakwaters of the outer reefs, more sand drifted until white dunes pushed up into the air. Eventually a coconut blown from Africa by the monsoon winds floated ashore to anchor the sand spit. Then another. In this way, some 1,192 little islands popped up to form this dhivehi raajie, or island kingdom, the Maldives.

Though their highest point is only six feet above sea level, these islands, just 300 miles due south of India, became a strategic stopover for traders. Persians, headed for the spice islands we now call Indonesia, sailed here on the southwest monsoon winds then came ashore from April to November, waiting for the winds to change to take them home again. Cowrie shells from the Maldives were prized as currency, and shells dating back to 2000 B.C. have been found as far away as China. Africans, British, Portuguese put in here and claimed parts of the atolls then pulled up and headed on.

During the past 20 years, a new wave of conquerors appeared. Armed with monogrammed bathrobes, umbrella drinks and massage oils, the best hotel chains in the world moved in, each claiming its own island. Since the Maldives are Muslim and alcohol is forbidden, the resorts are often separate, usually on their own islands, away from the local population.

Young Mohammed Shaweed’s father had been in on the first round of hotels, developing some lovely, if not extravagant, small resorts. Then, at age 46, he died suddenly during an address to the chamber of commerce. Shaweed, 19, stopped his studies in Malaysia and flew home to help his mother run the business and raise his brothers and sisters. Within a few years, Shaweed had married his high school sweetheart, turned his father’s business around and bought Rania from a sheikh in Dubai.

“At first I thought the yacht would be enough,” he says. “There are no luxury charter yachts in the Maldives and my idea was to have this and Cleopatra be the beginning of a small luxury fleet. The yacht could go from resort to resort, explore outer islands that most tourists never see, visit remote dive sites and gamefish grounds.”

“But then we wanted a picnic spot,” Shaweed, now 29, continues, “someplace within reach of Male, but far away from the other resorts”. He came across Water Garden Island, as he dubbed the tiny crescent of sand, in the middle of the Faafu Atoll. It was what you might imagine a perfect island to be: seven acres of pure and powdery white sand; an impossibly teal-blue lagoon; tall coconut palms and sea grapes anchoring it on the flat horizon.

And so what started as a picnic spot for Rania‘s guests has turned into one of the most luxurious and most private enclaves in the world. Though admittedly not accustomed to having two butlers (or even one), much less an entire staff at my beck and call, after a day or two I decided it could be amusing to exercise my privileges.

“Senthil, I’d like dinner tonight on that pavilion,” I informed the charming Indian butler, who tag-teamed with Saed, earlier that day, languidly pointing to one of the overwater pavilions on the islands’ western shore. I watched his face to see the reaction: “Yes, Miss Lisa, no problem,” he said, eyes scanning the horizon. And it wasn’t a problem; a table and chairs were carried out to the end of the dock and linen cloth and candles and the three of us took our seats. A grouper sushi had been served (caught by fishermen from the next island over), with four more courses to follow, when the skies let loose. A small army suddenly materialized with umbrellas (had they placed bets on how far through the meal we’d get before the rain arrived?), and our dinner party moved indoors.

Almost every day we asked Adham, the PADI dive master, to take us diving. For our checkout dive, we donned our scuba gear on the beach of Water Garden. I was prepared to just paddle around, see a few fish and get ready for a longer afternoon dive. But just 50 feet offshore the bottom dropped away in a sharp wall that nearly took my breath away. Six feet below I could see swarms of angelfish as clearly as if they were an arm’s length away. Flurries of smaller yellow and purple fish moved in and out of the coral like dance troupes across a stage, sea fans waving in applause.

“There are no other resorts nearby, so we usually have the dive sites to ourselves,” Adham explained as we motored toward another of the 40 or so dive spots in the area. Indeed, on our second dive, Adham reached out to hand-feed a hawksbill turtle. A spiny lobster with antennas as long as my arm peered out of a cave, giant grouper floated by as I watched for giant whale sharks that cruise these waters, docile behemoths that can grow to 40 feet.

The following day, the same atolls that had fascinated us under water scared the daylights out of me when I peered down from Rania‘s bridge and saw a coral head passing just yards from our speeding bow. I had been following along on the chart as our captain navigated toward a neighboring island. “The charts are all wrong, he said wryly. “The sands shift so much that unless you know these waters well, you’d likely run aground. Large yachts, such as Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich’s, move from atoll to atoll in the deep waters outside the reefs, but it takes a smaller boat, such as Rania, and a local skipper to thread the coral heads.

Ahead was a small native-owned island, where we maneuvered among brightly painted fishing skiffs to a dock. Children came running down sandy streets to see the boat, and then hid shyly behind the coral walls. Women, wearing the customary beautiful long tunics and pants, faces hid by scarves, only glanced our way. In turn we peered into a schoolroom where young girls, some wearing scarves to hide their heads and faces, others not, learned the Koran-surrounded, I noticed, by Barbie dolls. Out by the beach, a movie screen had been set up, seats made of fishnets strung between trees: Tonight’s entertainment would be World Cup soccer.

A man, standing on a ladder high in a palm tree, beckoned and greeted us. Wearing a traditional sarong, he showed us how he tapped the tree to make wine, and he sang us the age-old songs of the fishermen in a dialect all their own. Later, he climbed down and beckoned us toward a small house. “He would like us to try the palm wine he is making, Saed said. We sipped wine, as sweet and light as champagne. And I realized that the true luxury of Rania was not how far away this yacht and this island could take me from my world, but how close we could get to a side of the Maldives most visitors never see.

Contact: Rania Experience, (960) 67-40555, www.raniaexperience.com