No matter how you enter Charleston Harbor, the shoreline ahead is low under the big Carolina sky. Bridges arch over the Cooper and Ashley rivers, and an incoming freighter might loom high over the marsh islands.

Only when you find yourself docked and walking into the old town does Charleston rise around you like an apparition from the glorious past. Georgian and Victorian mansions gleam within frames of wrought iron. Church steeples pierce the sky. Live oaks shade streets cobbled with ship ballast stones.

It is like finding a lightly traveled pathway into historical America.

The path from City Marina or Ashley Marina, both full-service facilities on the Ashley River, leads to coveys of doves fluttering peacefully in the trees at the Battery, a park rimmed with 11-inch cannons and 13-inch mortars. The Battery looks toward the harbor entrance and Fort Sumter, where Confederate forces pounded Federal troops into submission in 1861. The Southern planters, fighting for their way of life, launched a war that would ravage the South and change the cultural landscape of America.

Today, the Battery makes a grandstand for watching yachts race off Charleston YC on Cooper River, once an anchorage for hundreds of windjammers loading rice and cotton for England.

Unbelievable as it seems, the colony began in the 17th century as a food base for Barbados. The island-smothered by sugar cane precious as gold-did not provide enough food for those who came to claim its product. The richest English investors rallied, and a group of speculators, Lords Proprietors of South Carolina, was born. The year 1670 saw the arrival of the ship Carolina on the Ashley River and a new settlement on its west shore. Charles Town village (today a restored state exhibit) moved to Oyster Point in 1680 and soon outgrew its initial purpose.

The leaders of the colony, plantation-savvy colonists from Barbados, imported slaves to work the virgin land. Charleston was an easy stop for ships sailing north with the Gulf Stream before heading off for Europe. By 1720, about 15 percent of all American exports (pelts, timber, pitch, tar and turpentine) went through the port. When the colony expanded to rice and indigo, the trade share increased. By 1770, it was 29 percent, and Charleston, the fourth largest port in America, became the wealthiest.

Opulent mansions on South Battery and East Bay still bear witness to the city’s past economic power. However, to truly immerse yourself in historical Charleston, you must walk through the oldest, once-walled part of town. Between Meeting Street to the west, East Bay to the east, Battery to the south and Cumberland to the north is a treasure chest of architectural pleasure and history.

On Meeting is an immense, red brick Calhoun Mansion from 1876 that recalls the brief period of recovery after the Civil War. The plaques on the smaller buildings tell important stories. The David Huger House, from 1760, housed the last Royal governor who found need to escape after Charlestonians joined the North in the patriotic cause.

Narrow streets such as Chalmers are lined by beautiful pastel-colored row houses, the walls of some showing iron ends of reinforcements holding together structures weakened by natural disasters. Many hurricanes have hit Charleston-the coast tends to suck the storms from the Gulf Stream-and 1886 brought a devastating earthquake.

Charleston can still charm visitors because of early preservation actions. At 8-10 Tradd Street, visitors will see a house topped by a gambrel, or “Dutch gable, the oldest type of roof from the 18th century. The house was saved by Susan Pringle Frost, the founder, in 1920, of the Society for Preservation of Old Dwellings, the first such organization in America.

This awakening to the value of older homes transformed East Bay’s fish market, a warehouse row and later a slum, into today’s Rainbow Row.

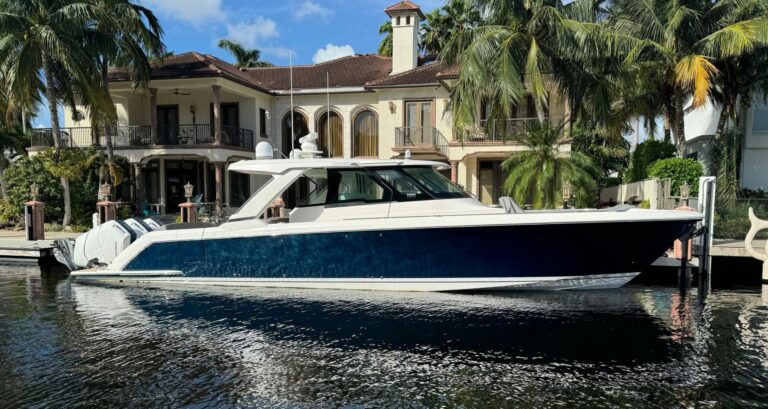

Charleston Harbor Marina, suitable for the largest yachts, looks upon Charleston from Mount Pleasant across Cooper River. This marina joins the Naval Maritime Museum, which boasts World War II warships.

The carrier USS Yorktown is the undisputed queen of the show, but she soon may be joined by the H.L. Hunley, a 40-foot, manually propelled Confederate submarine that opened a new chapter in naval warfare in 1864 by blowing up the USS Hussatonic before sinking herself. Salvaged in 2000, she is undergoing conservation, but a full-size model is displayed in the Charleston Museum.

The physical demands of touring Charleston’s treasures can be eased by sampling fine food. Charleston is, after all, home to Johnson & Wales University, a culinary institute. Seafood dishes such as shrimp and grits, seasonal oyster roasts and a “Low Country boil-of shrimp, blue crabs, sausage, corn on the cob, whole potatoes and whole onions-pass the local patron test.

If you like your seafood truly fresh, steer to nearby Shem Creek, where shrimp boats tie up to the restaurants.

And if you value the sea as more than a food source, visit the South Carolina Aquarium, which opened in 2000. The Charleston Maritime Center, with 30 slips on the deep water of Cooper River, is a short walk away.