It All Adds Up

Ever had a great meal out with friends and been shock-_shocked!-_when the check arrives? So many laughs, such great wine, the tiny appetizer everyone shared that was so delicious (“Let’s get another one!”)… it all adds up. Fortunately, at a restaurant you can sort out the charges right then and there. And even if it is a bit of a splurge, the problem usually won’t be any bigger than the indigestion that’s headed your way.

Believe it or not, there are people who run their boats this way (if this is what_ you_ do, please keep reading—you may be glad you did). As the months roll on, they just keep paying the bills and writing checks and talking to their boatyard and paying more bills.

Here’s a question: Would you run a business this way? Probably not…. And definitely not for very long.

“It’s absolutely a balance sheet,” says the owner of El Jefe, a 115-foot Derecktor motoryacht. “Whether you charter the boat or use it for personal pleasure…no matter how you look at your yacht at the end of the day, you really should look at it no differently than any other business that you conduct.” There’s a reason that successful businesses have established accounting practices: Their balance sheets tell the people holding the purse strings what’s happening. Over time, the spending on a balance sheet becomes expected and predictable.

Think of it this way: You’re at the helm and you notice your fuelburn numbers creeping up, higher and higher for the same speeds you’ve always made. You wouldn’t ignore that change—you would address it. Same with the boat’s finances: Changes or upticks in costs (and they’re rarely “downticks”) should be investigated and understood.

| | |

Depending on the size of your boat, you may have someone you can rely on. “It starts with your captain,” says El Jefe’s owner. “And if your captain is not cognizant of the fact that you look at the yacht as a business and you have certain goals and you have certain expectations, then expenses can run in multiples each month.” The bottom line, and that expression is apt here, is that anyone you invest with the power to make decisions about your boat needs to think about your boat—and your bank account—the same way you do.

“I treat this like a business, while a lot of [captains] just treat it like an open account and have fun and go for it,” says Brad Tate, captain of El Jefe. “We don’t have a specific budget, like ‘this is how much we’re going to spend on each line item.’ But really my job is just to keep things at a reasonable level.” Tate knows the drill, because the owner has communicated the yacht’s priorities to him. It also doesn’t hurt that Tate has a degree in finance: He reads a balance sheet and understands the boat’s budget. This is why the crew of five will clean the boat themselves, as one example. “We rarely hire dayworkers to help us out just because, in this economy, we don’t have a lot of 24- hour turnarounds like we used to,” says Tate. “We can get it done.”

Not everyone has five crew to help out, though, nor as much yacht as El Jefe to manage. So, what if there’s no captain to schedule the service or muster the crew to clean the boat?

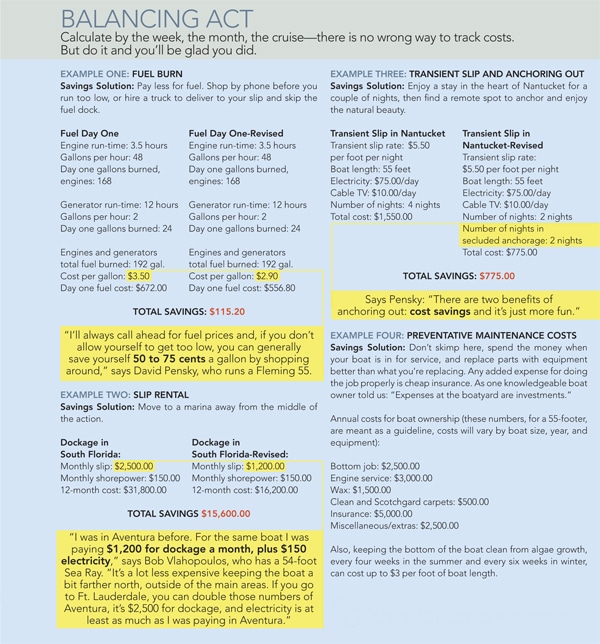

Take the case of David Pensky, who runs a Fleming 55 on long coastal cruises, both up to Maine and Canada and to the Bahamas. “I think the single biggest money-saving thing that I do is preventative maintenance,” he says. “And by that I mean timely oil changes, timely parts replacements. I think it saves money two ways. The most important is that, for the days of the year when the boat is in use, I don’t have breakdowns. The biggest cost is just not having the use of the boat at those times when I want use of the boat, when I’m on a cruise. I also find that generally the most expensive repairs are done away from home—a result of not having my regular people to work on it.”

By scheduling projects during the boat’s downtime, Pensky is able to have peace of mind on his cruises. But not all mechanical problems are predictable and avoidable. When he’s in some farflung port, Pensky does not look for cheap solutions. “When one thinks about how few days a year you use the boat and you divide it up by your total costs, losing two or three days because of a mechanical problem is very costly—even beyond the actual dollars and cents of the repair,” he says. “I try to go to the most reputable yard to get repairs done when I’m not in my home waters. Generally I’ll ask around. And I’ll call my mechanic at my home yard and find out if they have any associations in the area where I am.” His mechanics know the boat and can give advice to the local service provider, and hopefully speed the repair, saving invaluable time.

Another place where Pensky considers his costs is dockage. “We’ll do a combination of anchoring and docking [on long cruises],” he says. “Of course, anchoring out is much less expensive, and it’s also more emotionally satisfying.” When choosing his rental slips, Pensky takes the location of the marina into account, and always makes advance reservations. “If you have a reservation and need to change it because of weather or rescheduling, they’re very accommodating,” he says. “It’s easier than not having a reservation to get to where you want to be.”

Pensky doesn’t advocate taking the least expensive route. After all, cruising is meant to be enjoyable. “I find that, more important than the economics when I go into a dock, is a marina’s location and facilities,” he says. “There are choices between economy and quality of life—for example, we want to stay at a particular marina that is more expensive but so much more convenient, such as one of the more expensive marinas in Nantucket. We like to stay there for the convenience of having guests on and off the boat and being there. Then we’ll anchor out a few extra nights so we can offset some of the costs.” The remote anchorage is a rewarding change of pace, and one that cuts expenses.

Other owners use their boats differently. Bob Vlahopoulos lives in the Toronto area, but keeps his 54-foot Sea Ray in South Florida. He doesn’t dock his boat in the heart of Ft. Lauderdale anymore, and he can see the savings. But he also saves time. “It’s a bit harder to get to from the airport, from the commercial [airlines], but I fly [my own plane] into a small airport there,” he says. “When I bring my boat back from the Bahamas, it’s much easier to clear customs in Ft. Pierce than Ft. Lauderdale: It’s 10 minutes, you just drive by, they talk to you and you leave. In Ft. Lauderdale, you’ve got to run around, and West Palm is always busy.”

Changing your dock location means that you may have to run farther to get to your cruising destination, and stop for fuel along the way. But do your research and you may come up with another line item where you can cut costs. “If a guy is really smart he can look ahead to where he’s going to be traveling and he can find out what fuel costs are going to be,” says Fran Morey, director of service and product training for Grand Banks Yachts. “From marina to marina there can be a big swing, just like at the gas pump when you go to buy gas for your car, you can see a 50-, 60-, 70-cent change in diesel fuel. It makes sense, if you’re buying in bulk, if you’re going to buy 1,200 gallons, that there’s some opportunity to save some money.” And, perhaps counterintuitively, the quality of fuel at the outlets that work on volume may be better because the diesel doesn’t sit as long.

Leaving the boat in an exotic location while you jet home to reality for a few weeks may be another opportunity to reduce spending, with planning. “We buy our plane tickets in advance when we travel,” says Pensky. “We try to make our arrangements well in advance in order to get the best fares. And we fly with airlines that don’t charge for changes, such as Southwest.”

While we don’t advocate penny-pinching, we think that tracking the dollars on a regular basis and directing them more effectively will help you get more out of your boat. “Owners are faced with decisions on safety, cosmetics, look, comfort,” says the owner of El Jefe. “You have decisions that you have to make: Do I buy $60-a-yard carpet or do I buy $20-a-yard carpet and change it every two years? Do I put the money into the machinery? Do I put the money into the cosmetics? Do I put it into the comforts or the electronics? One thing’s for sure, there’s always someplace to put the money.”

| | |