FLIR Thermal Camera

As a kid, my first job on board involved standing watch on the bow during middle-of-the-night landfalls and foggy Maine cruises, scanning for the telltale clatter of a buoy, the throaty groan of a diesel engine or the misty silhouette of a passing island. While my dad always sailed with top-of-the-line equipment, the marine-electronics offerings were considerably “thinner” in the early 1980s than they are today. Sure we had radar, but the patchy blobs that populated its small, monochrome display depicted large boats or ships, not logs or kayaks. Flash-forward to 2006, when technology giant FLIR introduced a first-generation thermal night-vision camera for the marine market that was based around technology that it had developed while working on military and automotive-industry projects. By 2007, FLIR was building a line of fixed-mount cameras, including static models (no movable sensor) and dynamic units that could pan and tilt their sensors. Over time, the company shifted its development focus to its dynamic units and handheld cameras.

For the large-yacht crowd this wasn’t problematic, but owners of more modest-size yachts were sometimes left staring at radar screens, wishing for the ability to see through the murk, much as I did in my early sailing experiences. Fortunately for this market, FLIR recently announced its new line of fixed-mount, static MD-Series thermal night-vision cameras. The MD-324 ($3,499) uses a 320×240 VOx microbolometer to sense and render thermal imaging, while the MD-625 ($4,499) uses a 640×480 VOx microbolometer to provide higher-resolution video and greater range. Both MD-Series cameras have just three cables — power input (12 to 24 VDC), Ethernet and video-out — making for straightforward installation and integration.

Also of interest to all boaters are FLIR’s newest-generation handheld, weatherproof cameras, the First Mate II ($1,999) and First Mate II MS ($2,999). These small, travel-friendly units feature a built-in battery and color LCD display. Or, for users who want to record both still and video footage, the First Mate HM-Series ($3,149 to $8,999) features a video-out port, allowing the cameras to deliver their feeds to larger screens or compatible multifunction displays (MFDs).

“We have a two-word mission,” said Andy Teich, president of FLIR’s commercial systems division. “Infrared everywhere.” A big part of that mission has been lowering its costs. “We get our volume business from the automotive market, which has allowed us to bring down the price for the marine market,” he said, adding that FLIR supplies thermal night-vision equipment to high-end carmakers — including Audi, BMW and Mercedes, which demand unflinching performance, irrespective of ambient light.

Traditional image-intensification (aka night-vision) equipment requires a certain amount of light to operate, either from an ambient source (e.g., the sun or moon) or from a built-in illuminator (e.g., LEDs) that generates near-infrared light, which the device uses to light up objects in front of its sensor. This light is then reflected back to the unit, and the sensor uses this information to render a greenish, glowing image of what’s “out there.” While this system works in certain applications, it has some significant drawbacks, especially for drivers and boaters. For starters, since night-vision technology relies on both broadcast and reflected light, its effective range is typically limited, which isn’t compatible with fast-moving vehicles. Moreover, fog, rain and snow immediately reflect light (either emitted or natural) back at the camera, restricting its ability to render imaging.

| |The handheld FLIR MS-224 offers great performance for every budget (left). FLIR’s HM- 224 gives a user the ability to record video and still frames (center). This handheld FLIR HM-307XP+ provides the sort of serious features and thermal-imaging abilities normally found in a fixed-mount camera (right).|

FLIR’s thermal night-vision cameras rely on technology that senses minute temperature differences — not reflected light — to render a scene. Teich said FLIR’s sensors are sensitive to 50 millikelvins, or one-20th of a degree Celsius. “It works much better on boats because it’s a passive technology that’s not dependent on [ambient or emitted] light and it isn’t hurt by light fog or rain,” said Teich. “Thermal imaging can see through total darkness because it can sense the temperature differences in the thermal energy that’s emitted from all objects that are above absolute zero.” (For anyone who’s not a physicist, “absolute zero,” or 0 kelvins, is a balmy minus 273.16 degrees Celsius, or minus 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit.)

This impressive sensitivity allows FLIR’s MD-Series cameras to spot a man overboard from 1,500 to 2,700 feet out (model depending) and a small boat from 4,200 feet to 1.2 nautical miles. The handheld First Mate II units can detect these same target types from 1,050 to 1,480 feet and from 2,940 to 4,100 feet (model depending), and higher-end FLIR models boast significantly greater range, albeit for a higher price. FLIR’s processors quickly render the scenes in front of their sensors into a flowing video feed; users can electronically zoom in and out and toggle the image polarity between black hot, white hot and marine red.

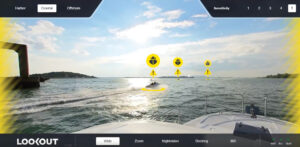

“If you can watch TV, you can use thermal night vision,” Teich said. “Radar is more complicated — it’s hard to determine what something is.” FLIR’s MD-Series cameras feature a cable that delivers NTSC or PAL video output; the video stream can be easily displayed on any monitor/TV, and its Ethernet connectivity allows it to play nicely with compatible MFDs. Ethernet connectivity also allows users to enjoy wireless user-interface control via Apple iOS devices. Additionally, the video feed can be simultaneously streamed to multiple screens and devices, which, Teich said, is a common practice on yachts that operate in piracy-prone waters, because owners and crew can keep watch over the vessel from myriad locations throughout the yacht.

Interestingly, thermal night-vision equipment performs nearly as well at 1300 hours as it does at 0100 hours. “The sensors don’t detect light,” Teich said. “The image looks the same, except the sun can warm up objects, making them easier to see.” This is especially useful for studying sun-covered waters, since an operator can simply look at a display, rather than squinting futilely. However, while light and complete darkness are irrelevant, thermal energy doesn’t transmit through water, making heavy precipitation a challenge. “There are gradients of moisture,” Teich said. “Light fog isn’t a problem, but there’s a gray area between [this] and solid water.” Likewise, thermal night vision won’t help anglers spot fish, but it will help them to identify heat gradients on the water’s surface, as well as disturbances created by baitfish.

Teich suggests that the MD-Series target audience is likely trawlers and other vessels whose bows don’t lift substantially at speed, because its static camera doesn’t articulate. The MD-Series could also be a great match for sailboats because the unit’s weatherproof “ball” head, which can be mounted either “ball-up” or “ball-down,” is compact (seven inches tall with a six-inch beam) and lightweight (about three pounds), meaning that it won’t add much weight aloft or create excessive windage. Its small size also makes it an ideal stern-facing option for larger power yachts that already have a bigger FLIR camera peering forward. The handheld First Mate II/MS/HM Series cameras are great additions for all yachts, either as the vessel’s primary eye or as dream equipment for tenders.

While some of navigation’s romance was arguably lost when sextants (and junior lookouts) were retired, anyone who has ever made a complicated landfall in Down East fog will quickly discover a newfound love for thermal night-vision cameras. And thanks to FLIR’s new, more affordable MD-Series — as well as its handheld First Mate II/MS/HM Series — “infrared everywhere” could evolve from an in-house mantra to an on-the-water reality.