Hinckley T44 Mark II

Ryan, my skipper for the morning and co-owner of Upshort, hull No. 1 of the Hinckley T44 EX MKII motoryacht, smiled a good morning greeting as he ambled along the dock. The eastern sky glowed faintly, like the loom of a distant city late at night. On the dark side to the west, the brightest of stars twinkled their goodbye. The clock ticked toward 0615.

Little Traverse Bay snoozed under a blanket of chilled calm, the surface resembling a mediocre computer rendering of a quiet seascape. When the glacier from the most recent North American ice age sculpted the landscape in this area, it dug a 170-foot trench just for this bay. It’s the deepest natural harbor in all the Great Lakes. The bay’s water changes color with the sky — gray/blue before sunup, pastel green/blue reminiscent of glacial meltwater in the early morning sun, and the cobalt blue of the Gulf Stream when the sun climbs to its zenith and shines from a cloudless sky.

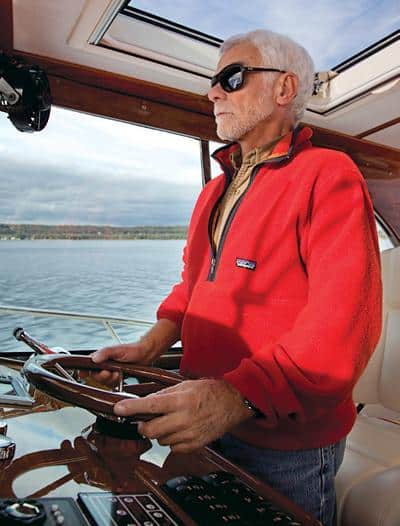

We idled out of the marina in our best imitation of Humphrey Bogart and Walter Brennan in To Have and Have Not. Stealth was the order of the moment, not because we feared disturbing sleeping residents of the condominiums behind us. We simply didn’t want to offend the spirits by breaking the peace of the morning. So, we ghosted along, the T44’s Cummins diesels murmuring to themselves while Ryan and I chatted.

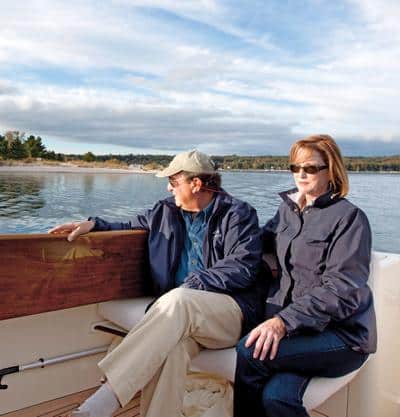

During a visit to Southwest Harbor, Maine, in 1997, he told me, the sight of five Picnic Boats under construction at Hinckley’s yard — their simple, graceful beauty — smote him mightily. To celebrate his new love, he bought a denim shirt with the company’s logo on it. He still wears it. When he was ready to buy a cruiser/day boat, he and his wife, Meg, who’s really the skipper of Upshort, knew that the T44 was just the right size. “It fit our needs perfectly,” he said. (The owners wish to remain anonymous, so I’ve called them Ryan and Meg.)

We motored southeastward, still at no-wake speed. Ryan sipped from his cup of coffee, tweaked the JetStick now and again, and told me that his only regret as the owner of Upshort is that he never gets to see her from a distance, cleaving the water at displacement speed or dancing atop the surface, hellbent for the next destination at her cruising speed of 30 knots. I understood his feeling, but I was perfectly content to hang out in the pilothouse, my perch on the Stidd buddy seat as comfortable as I could wish and the view outstanding.

Like many traditional New England designs, this second generation of the T44 invites everyone aboard to relax on the settees within the shelter of the pilothouse or to gather in the cockpit for a drink and a laugh. Folks who choose to stay out of the sun have only to open the power-operated hatches in the overhead and the power side windows to bring the outside inside. The boat’s open arrangement and single step between the cockpit and the bridge deck encourage everyone to mingle. A hefty door in the center of the transom opens onto the teak swim platform. Ryan said that he likes to let Upshort drift into the sandy shore stern first, coming to rest in waist-deep water when the anchor bites. An anchor off the stern steadies the boat while everyone swims.

The sun peeked over the horizon and set fire to the high points of Harbor Springs, Michigan, behind us. Above the shoreline of Petoskey State Park, maybe a third of a mile off our bow, a wisp of cloud arced across the sky like a brush stroke. It glowed a pale pink, as though the brush needed more paint. Hugging the inshore waters off the port quarter, sea smoke, created by the cold night air over warm water, mesmerically undulated, advanced, retreated, opened its maw and closed it again. We motored into it and let it wrap us in gauzy obscurity. Within several minutes, the sea smoke broke into a handful of amorphous shapes and evaporated into the sun’s warmth.

Across the mouth of the bay to the west, the Little Traverse lighthouse stood like an exclamation point at the end of a declaration. It marks the tip of Harbor Point Peninsula, a crescent-shape private enclave of summer homes, protected by a guard at its only shoreside entrance. Ryan opened the throttles, and we planed over for a closer look. The T44 MKII accelerates with a fair amount of authority, certainly briskly enough to satisfy all but the most thrill-crazed pilot. Ryan brought Upshort close to the shore so we could see details of the old light-keeper’s house and the light’s tower. No longer manned, the light continues to operate electronically. The JetStick in docking mode allowed Ryan to maneuver the T44 as though it were an eighth-scale model. (As many times as I’ve seen this device in action and used it myself, it never ceases to amaze me.)

By then, the sun had climbed too high for the best photography, and hunger pangs gnawed. We headed back to the dock, in company with Marty Letts, Hinckley’s director of sales for the Great Lakes, and photographer Billy Black aboard the chase boat, to discuss where to go for breakfast. Like any small town that depends on tourists for its economic base, Harbor Springs has a variety of coffee shops and homey small restaurants. Ryan lobbied for Mary Ellen’s Place, so that’s where we went.

The restaurant began life in 1928 as a newsstand. Mary Ellen Hughes bought the business in 1988 and turned it into the breakfast and lunch restaurant it is today. She works the restaurant every day, and her bright smile and easy manner no doubt encourage year-round residents of Harbor Springs (about 2,000) and summer folks to visit often. In fact, the entire town has that kind of friendly vibe. It felt like a favorite wool sweater on a cold winter’s day, partly because of its 19th century architecture and small physical size (1.3 square miles), but the warmth and openness of its residents has to be the main reason.

We parted company after breakfast, agreeing to meet early in the afternoon for a cruise to Charlevoix, followed by my turn at the helm in the evening. Meanwhile, I walked. Harbor Springs has a short coastal plain, which terminates in a steep, but short, rise to a bluff that overlooks the city. East Bluff Drive parallels the waterfront but at about 300 feet above it, and from this street, I had a panoramic view of the harbor. During the stroll, I discovered a boardwalk and series of staircases, which serpentined the nearly vertical face of the bluff under cover of fairly dense foliage.

A short while after lunch, we reconvened for the hourlong cruise to Charlevoix. The city sits on an isthmus that separates Lake Michigan from Lake Charlevoix, which drains into the former via the very short Pine River/Round Lake waters. The Pine River is narrow and shored up on both sides with steel bulkheads. A lighthouse marks the mouth of the river. The city, permanently settled in the years following the end of the Civil War, is roughly twice the size of Harbor Springs in population and landmass and once was a thriving industrial city served by rail from the south.

Charlevoix has always been a resort destination for wealthy vacationers. In the 1880s, a group of professors from the University of Chicago formed an association known as the Chicago Club Summer Home. The Belvedere Club and Sequanota Club soon followed. Summer residents arrived by rail and passenger liners. The Belvedere and Chicago clubs still exist. Many of the private homes along the shores of Round Lake have integral boathouses, one of the most impressive belonging to the Winn family — of Four Winns boat fame.

On the return trip, we stopped at Petoskey, the real commercial center for the area, and Bay View Harbor, a relatively new development. Petoskey offers a handful of shoppers’ berths in the municipal marina, so anyone who cruises in this area can easily replenish the boat’s stores. Bay View’s harbor was a stone quarry and is quite deep. Residences rise above boathouses along the eastern side, and a massive stone breakwater shelters boats tied up at the marina. On our first night in Harbor Springs, Letts and his charming wife, Susan (a landscape architect), took us to dinner at Not Just a Bar restaurant. The local whitefish was terrific.

At last, I had my turn at the wheel of Upshort. Like the other models of the Talaria series, the T44 MKII feels substantially larger than she is, even as she treats the pilot to an unmistakably sporty driving experience. Upshort felt planted — a term commonly used by automotive road testers when they describe the behavior of a luxurious sports car. Her hydraulic steering was accurate and smooth, but because I was steering the thrust, I needed several minutes to adapt to its response. On the other hand, the T44 seemed to turn more quickly and accurately when I steered by rotating the knob of the JetStick. She cornered with a reassuring lean into the turn and lost only about seven knots pinched into a tight radius at maximum revolutions per minute. She comes onto plane at 2100 to 2400 rpm and likes the tiniest bit of trim tab to run at the hull’s optimum angle of attack. At her cruising speed of 3000 rpm, or 31 to 32 knots, the engines run at 85 percent load and burn 58 gallons of diesel per hour.

Belowdecks, I found the customary Hinckley touches — high-quality cherry joinery, top-notch equipment and a thoughtfully designed arrangement plan. The owners’ stateroom is in the bow and has a large island berth on the centerline (stowage under) and two hanging lockers, which likely will be enough for a week of cruising. The head and shower appear to be spacious enough for all but the largest humans. The dinette converts to a double berth for occasional guests.

Bear in mind that the T44 MKII is not a cursory makeover of the previous model. Hinckley’s updates are significant, to wit: more powerful engines (550 horsepower vs. 480 horsepower); custom Hinckley electric sliding side windows and hatches, which are larger than before and rest in hidden stainless-steel frames; an improvement in the ergonomics of the pilothouse and helm; better sight lines at all speeds; and other improvements.

Our final night in Harbor Springs found us in New York — actually The New York, a fine restaurant on State Street next to Hinckley’s office. The chef and owner, Matt Bugera, offers his traditional house-made soups, fresh whitefish (which I ordered) and prime steaks in a setting that recalls the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His wine cellar contains about 300 varieties, and the food is as good as I’ve eaten anywhere. Ahh, a special boat, good people, fine food and a great cruising ground; I was looking forward to my return before I had even finished my coffee.

LOA: 44’0″

Beam: 13’6″

Draft: 2’4″

Displ.: 30,100 lb.

Fuel: 500 gal.

Water: 100 gal.

Power: 2 x 550 hp Cummins QSC 8.3 diesels

Base Price: $1,689,000

The Hinckley Co., 401-683-7005; www.hinckleyyachts.com