Designing and building a large custom yacht and getting it right is a challenge no matter how competent the players. While the 194-foot Oceanco Pegasus is noteworthy for her splendid design and execution, what really sets her apart are the strong relationships and valuable experience that influenced her creation.

Owner Ronald Tutor started with a 57-foot Chris-Craft in the 1970s. In 1990, he met Ken Denison, then vice president of sales and new construction at Broward marine. Tutor eventually owned 103- and 130-foot Browards, and Denison put him together with Capt. Freddy Appleton. About five years ago, Tutor told Denison, by then owner of Broward Yacht Sales, that he wanted a larger boat. They talked with a number of yards about creating a large yacht capable of cruising the world with a proper owner-crew arrangement, and they selected Oceanco to build her. Its chief executive officer, Richard Hein, had worked with Denison as a designer in the 1980s.

New construction projects have grown in dimension during the past 15 years, but this reunited group of old friends-older and wiser and paired with an experienced owner-proved up to the challenge.

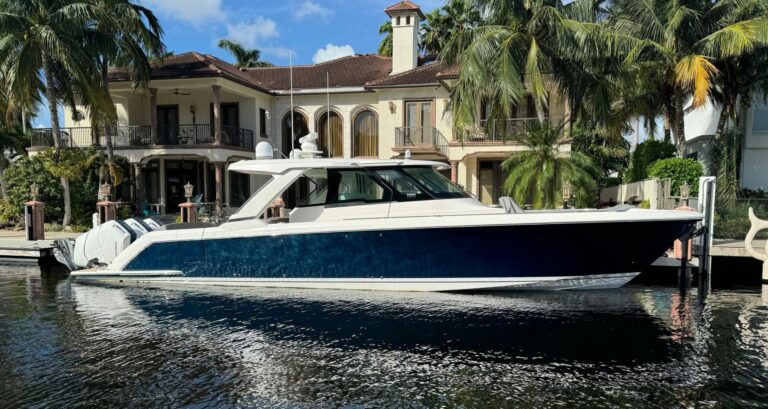

Pegasus is an impressive sight, even in the company of other large yachts. Her dark blue hull visually adds length to her silhouette and disguises the dimension of her superstructure, which is rather full-bodied compared with some of today’s more rakish designs. The result is tastefully modern and should remain pleasing to the eye long after trendier designs reveal their age.

This direction in styling also serves a practical purpose. “Our intention was to create an attractive modern design, however, Mr. Tutor was not willing to compromise the interior layout simply to stretch the styling envelope, Hein said.

Often, as length overall soars past 150 feet, public spaces and accommodations do not benefit proportionally. Tutor’s experience taught him the pleasing effects open interior areas and generous overhead heights create, so he crafted the interior layout personally, accenting the spatial relationships with beautifully detailed and crafted hardwood joinery and a generous allotment of handpicked stone.

In proper yacht fashion, the entry foyer is to starboard, amidships on the main deck. This entry point allows convenient access to the saloon and formal dining area aft, and to the master suite forward. Stairs here lead up to the sky lounge/theater, and stairs in the saloon lead below to five guest suites and a gym that also serves as the spare stateroom for professional staff.

Main deck access to port is reserved for the crew and leads directly to the commercially equipped galley and six crew cabins belowdecks. The captain’s cabin and office are adjacent to the pilothouse, which is appropriate for a vessel of this class. Appleton has a crew of 12, and as is typical for a yacht this size, roughly a third of Pegasus‘ interior volume is dedicated to crew services and ship’s machinery.

In a properly designed yacht, attention is focused on isolating the owner’s party from the ship’s business. On Pegasus, belowdecks volume from amidships forward is dedicated to machinery and crew. The galley and service areas are centrally located on the two upper decks, and the crew can move about without transiting owner and guest areas.

Still, all is a balance.

“Too often, designers are more concerned with crew flow than the comfort of the owner’s party, Tutor said. “My goal was to maximize usable interior space while still giving the crew comfortable quarters and room to work.

Exterior public areas aft on the main and pilothouse decks are designed for entertaining or casual dining. The flying bridge, more than 90 feet long with multiple seating areas, a full-service bar and a jacuzzi, is dedicated to the owner’s party. A day head is located conveniently in the arch.

As there is no flying bridge helm, Appleton operates the boat from the pilothouse and uses one of the wing stations for maneuvering in close quarters.

A 30-foot Intrepid and a 20-foot Novurania are tucked neatly into the superstructure on the pilothouse deck and are deployed on cantilever-style davits that extend from pockets in the superstructure. Other water and land toys are stowed on the flying bridge and in the transom garage. A section of the transom lowers and serves as a 12-by-30-foot “beach.

Oceanco built Pegasus‘ steel hull and aluminum superstructure at its Durbin, South Africa, facility. With her engines and generators installed, she was transported by ship to Oceanco’s finishing facility in Alblasserdam, Holland. Like most Dutch-built yachts, Pegasus‘ construction was a team effort. Subcontractors installed her systems, worked on her interior and handled exterior fairing and finish.

She is Lloyds classed and built to MCA Code. The rules prescribed by the latter are a safety standard for charter vessels that was established while Pegasus was under construction. Appleton felt it worthwhile to seek the certification.

“While we are primarily a private boat for the owner’s family and friends, Mr. Tutor wants the machinery operational and in use so it does not decay, Appleton said. The boat is expected to charter about six weeks a year.

The MCA requirements were handled discreetly. Watertight doors are hidden in the joinery. High-impact glass is used instead of storm shutters. The emergency generator is integrated into the ship’s power grid so it will not atrophy.

When a yacht’s length exceeds 125 feet, there is some debate about whether a displacement or semi-displacement hull is appropriate. In terms of resale, this issue tends to be as trendy as styling, although the tradeoffs for either are quite tangible. A large displacement hull is most efficient at hull speed and, because of hull form, is limited to deepwater ports. While the shallow waters of the Bahamas may not be an option for such vessels, the easier motion, efficiency and range make more distant destinations practical. A semi-displacement hull is capable of more speed given more fuel and generally carries less draft.

“I had two semi-displacement yachts and enjoyed them, Tutor said, “but I was committed to traveling the world, and a full displacement design was appropriate.

After her first summer season in the Med, Pegasus ran to Gibraltar, the Canaries and then to Ft. Lauderdale. The crossing took just 12 days, including playing a bit of cat and mouse with a hurricane. Her pair of 1,650 hp Caterpillar 3512s burn 150 gallons per hour at 14.5 knots and 110 gallons per hour at 13 knots.

The soft, full lines of a displacement hull typically have a less aggressive roll period in a seaway or at anchor. This quality is further enhanced on Pegasus by a sophisticated KoopNautic active stabilization system that includes oversize fins with extremely responsive actuators. The system is designed to operate under way and at rest.

“The test data indicates the system reduces roll at anchor by 80 percent, Appleton said. “It definitely does that, if not more.

As Denison pointed out, Pegasus is a European designed and built yacht, but because of the input from Tutor and the team he assembled, she is really a byproduct of the evolution of yachting in America.

“We all met building smaller boats, Denison said. “I guess we’ve grown up.

Contact: Oceanco International, (011) 377 93 10 02 81; oceanco@oceanco.mc; www.oceancoyacht.com.