“Always scan well ahead of the bow,” cautions Peter Vermeulen as I take the helm of his Protector Hauraki 40. Despite having sailed extensively, I have zero experience driving anything like Vermeulen’s 550-horsepower rocket ship. I ease the throttles forward and concentrate on finding a smooth line. The Protector makes neat work of the chop that’s roiling Johnstone Strait, instigated by the fast-moving currents, epic tidal swings and ricocheting winds that define cruising off Vancouver Island.

“Port bow, half-mile out,” says Vermeulen. I bank to starboard before spotting the floating menace, no doubt spillage from the logging industry. The Protector rolls comfortably to starboard, her inflatable tube acting like a ski edge carving through chalky snow. We blow past the partially submerged log and I resume course, smiling because, while these waters aren’t exactly benign, we have the perfect log-dodging tool.

Provided, of course, that our eyes stay sharp.

The idea was simple: four men, four days, one Protector Hauraki 40 and the objective of seeing how far north we could cruise in a tight round trip out of Seattle. Despite day one’s relaxed late-morning departure — a luxury specific to cruising on fast boats near the summer solstice — we reached Port Townsend, Washington, before noon, including a stop to watch a gray whale frolic. Vermeulen and I live in Seattle and are accustomed to seeing whales, but this is new stuff for Olin Silverman, 7, of Lake Tahoe. After the leviathan submerged, Olin enthusiastically recorded his encounter on a list that Ralph Silverman — Olin’s dad and our fourth companion — helps him organize.

Our bow soon points across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, an area notorious for lumpy waters. As expected, our horizon is strewn with confused swells of four to eight feet. I brace myself for our first big hit, but the boat’s tubes absorb the energy impressively. We cruise through San Juan Channel’s protected waters before clearing Canadian customs in Bedwell Harbor, British Columbia. After a brief fuel stop in Nanaimo, we punch north to Campbell River for the night, some 214 miles as the eagle soars from Seattle. While a trawler might take five days to make this passage, our props have spun for only six hours.

The water’s surface starts changing before we even enter Seymour Narrows the next morning. Container ships calculate their passage through here to coincide with slack waters; even whales wait for favorable tides. Not us: Vermeulen enters Seymour Narrows doing a casual 30-plus knots.

Clearing Seymour Narrows, we enter Johnstone Strait. The hills are awash in the deep greens of early summer, their upper flanks frosted by the misty clouds that cling to the moss-heavy branches. Life begets life in this temperate rainforest, which extends down exactly to the high-tide line. I take the helm and receive my first high-speed driving lesson. Ralph mans his iPad, loaded with a Navionics chart-suite app, while Vermeulen studies paper charts and the chart plotter, looking for “entertaining” skinny-water haunts.

I throttle back before we arrive at Matilpi, a former Indian village. We drift within feet of shore, taking in the stark-white beach that sharply contrasts with the surrounding landscape. This is actually a midden, or garbage heap, where native people once discarded spent shells, bones and kitchen debris — a bit more welcoming than their modern-day equivalents.

Vermeulen takes the helm and we race off to explore new areas, the most engaging being Baronet Passage. Ralph and I study the charts, and everyone scans for logs as we approach at pace.

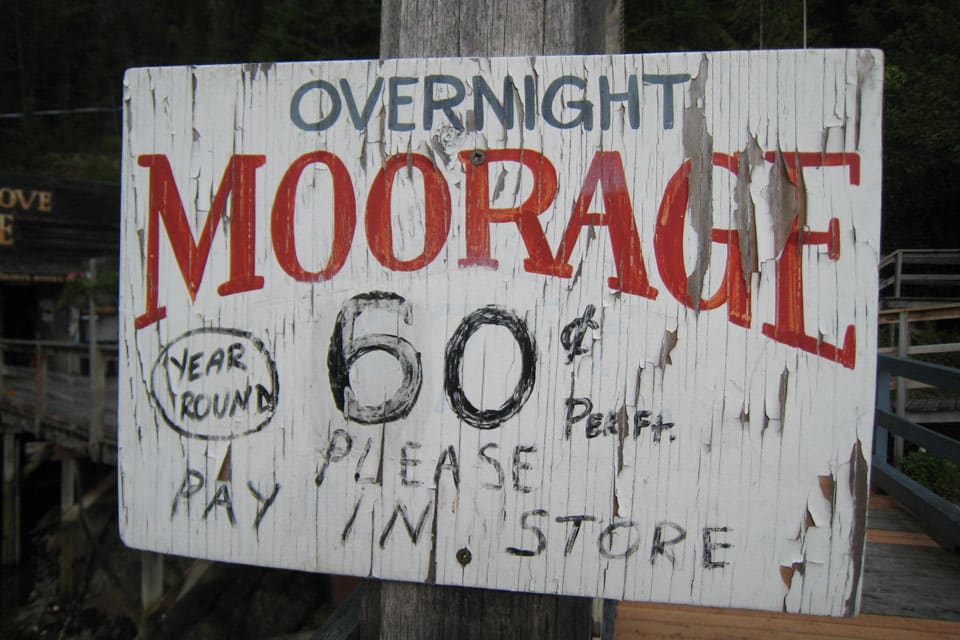

We arrive in Telegraph Cove around 1530 and savor the atmosphere of this former logging and cannery town. A rough-hewn boardwalk wraps past a smattering of shops, whale- and bear-watching operations, restaurants and our hotel. The most interesting attraction is the Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Interpretive Centre, which features a complete fin-whale skeleton.

After a salmon dinner at the Killer Whale Café, we motor over to Swanson Island, where we’ve been advised that bears regularly frequent the desolate beaches in the evening. While Ursus arctos horribilis proves elusive, we savor the quiet beauty of conifer-cloaked hillsides, bald eagles and these seldom-seen rivers. “After so many years of sailing, to be able to get here so quickly makes you realize just how great our backyard is,” Vermeulen says.

We wake up the next day to bluebird skies and cruise leisurely to Desolation Sound. I take the helm before we enter Sunderland Channel. The wheel is steady as we approach the first whirlpools, but it jerks slightly when we hit a serious swirl. I correct, but the bow immediately finds another depression. Still, the Protector feels rock-solid.

The whirlpools intensify as we approach Dent Island. “Nobody would go through these holes and rapids on a slow boat,” Vermeulen says laughing. “But with 550 horsepower, we’ve got the power.”

Growling stomachs eventually direct us toward the Dent Island Lodge, a spectacular property owned by the Nordstrom family. Although the lodge welcomes the public, the meticulously maintained grounds, buildings and cabins give off a decidedly exclusive feel. A sumptuous lunch, served in a dining room with sweeping views of the harbor and the seaplane runway, reinforces our impression.

While it’s tempting to stay here, we’ve got only 24 hours left to return to Seattle. We push south-southeast through Desolation Sound toward Nanaimo. Vermeulen advises a quick detour to Teakerne Arm, where waterfalls pour into the mostly sweet-water inlet. We cut our engines and float into a tidy alcove.

“Hey, Olin, are those oysters?” asks Ralph. At Olin’s direction, we ease the bow toward a shell-encrusted wall. While most 7-year-olds daydream about ice-cream cones, Olin attains gastronomic nirvana with his first freshly harvested oyster. Vermeulen aims the bow toward Nanaimo, and the shucking crew ensures that he receives regular dividends.

Perhaps it was complacency triggered by the flawless evening light or the dramatic views of snowy peaks — or perhaps because partially submerged logs are really hard to see — but our luck decisively ends with a boat-shuddering thud! We immediately kill the power and inspect the port outboard, which took the full hit. All is fine, but this serves as a stark reminder of the realities of piloting log-strewn passages.

The next morning we take the more sheltered route down the Strait of Georgia and into Skagit Bay, Washington, via Deception Pass. We enjoy fast cruising all the way to the Roche Harbor customs dock, where we stock up on enough victuals to last us until Penn Cove, where Ralph swears the world’s best mussels await us at the Captain Whidbey Inn.

We reel off miles, spotting a sandbar that’s serving as a temporary rookery for 20-plus bald eagles, doubling Olin’s count for the trip. We barely finish exchanging high fives before the Deception Pass Bridge heaves into view. Again, the charts, iPads and chart plotter are carefully consulted as Vermeulen masterfully weaves past known rocks.

Arriving at Penn Cove, Ralph braves frigid, knee-deep water to retrieve our to-go order from the Captain Whidbey Inn. Instantly, the afterdeck is awash with the decadent smell of butter-sautéed garlic and — Ralph was right — the world’s best mussels. Full bellies and lumpy seas carry us back to Seattle, where we return some 80 hours after departing.

“Removal,” said Vermeulen, sensing my final question. “That’s the reason for owning this boat.”

I consider his philosophy. While some people might question the sanity of dropping serious coin on an inflatable, I realize that it is among the best choices for safely tackling this sort of high-speed adventure cruising — and even then, you’d better have a damn good log spotter.

Protector Boats, 877-664-2628; www.protectorboats.com