The good news was the small amount of commercial traffic on the Hecate Strait, the wilderness waters separating Haida Gwaii from mainland British Columbia. But our five-person crew delivering a high-performance sailboat had no radar. Instead, we had a listen-only AIS receiver populating automatic identification system targets onto our chart plotter. Like all VHF radio-based communications, its range was limited to line-of-sight communications. So, we maintained a rotating watch.

During a night watch off Vancouver Island’s desolate west coast, I found myself wishing that AIS range could be extended. Now, a few years later, there have been some interesting developments involving aggregate terrestrial AIS and satellite AIS data.

To be clear, AIS data is transmitted and received via VHF-FM frequencies by a vessel’s AIS transceiver (or receiver). It is displayed on its networked chart plotter or multifunction display. AIS-VHF data is near real-time, meaning its GPS-based position information is accurate, but its range is limited.

Stepping into a different information ecosystem, government agencies and private companies also collect AIS data, which they aggregate and share with (or sell to) third parties. While internet AIS data isn’t new, two apps—PredictWind and savvy navvy—recently started offering it. Better still, PredictWind’s DataHub can download PredictWind’s internet AIS data, convert it to NMEA sentences, and share it with networked MFDs, navigation software and devices.

Internet AIS data isn’t the same as AIS-VHF data. Besides being aggregated, it’s older and less dependable than AIS-VHF data. But if treated with healthy skepticism, it can be useful for big-picture situational awareness.

Internet AIS comes in two forms: terrestrial- and satellite-based. Shore-based AIS monitoring receivers collect AIS-VHF data from passing vessels. These stations can be owned and operated by port authorities, government agencies or private companies. These listening stations are limited to line-of-sight ranges, but—thanks to their physically taller antennas—this reach often greatly exceeds ship-to-ship communications. Once terrestrial AIS data has been collected, it’s typically pushed onto internet servers as aggregate data, where it can be leveraged by third parties.

While it wasn’t originally believed that low-Earth-orbiting satellites operating around 150 to 1,200 miles above the brine could receive AIS signals, a proof-of-concept project launched in 2009. It was financed by the US Coast Guard and yielded happy news: Some AIS signals can be detected. But given the distances involved and AIS’s bandwidth-sharing scheme, Class A transmissions (mandated aboard most commercial vessels) typically outcompete Class B broadcasts.

Government and private companies have launched myriad LEO satellites that receive AIS transmissions, which they aggregate, process and relay to ground stations. From there, it’s pushed to internet servers.

Unlike terrestrial AIS data, which is usually free, satellite AIS data can be paywall-protected. The MarineTraffic app and website, for instance, has often-free terrestrial AIS and for-a-fee satellite AIS data. Likewise, Pocket Mariner apps have long delivered terrestrial AIS data to Android and Apple devices.

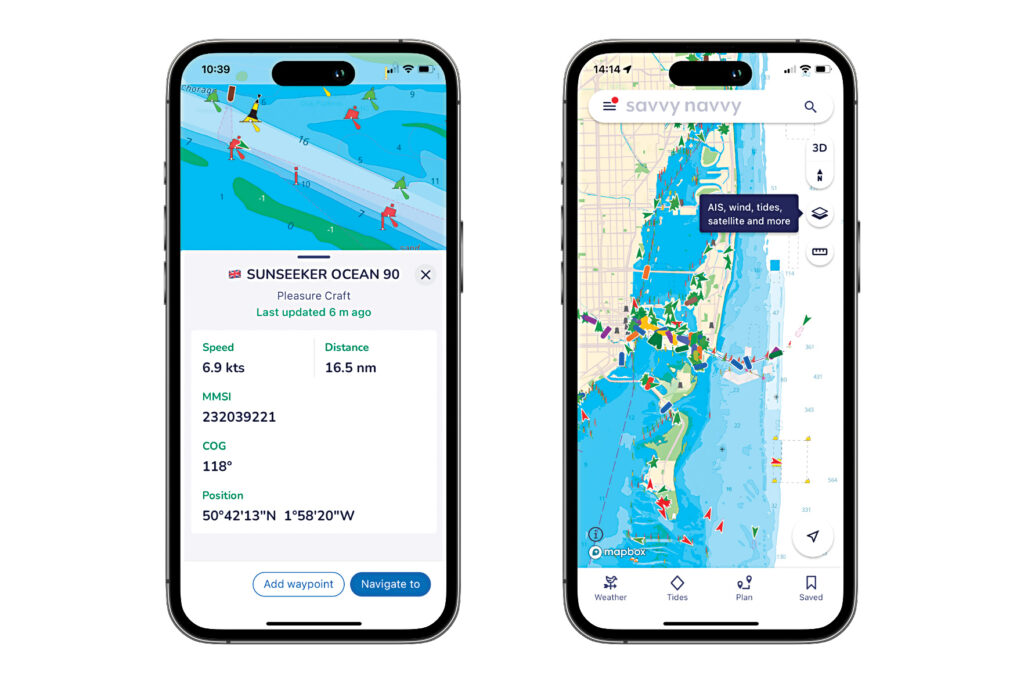

More recently, the PredictWind and savvy navvy apps started offering “over-the-horizon AIS,” which is marketing speak for internet AIS data. Both apps offer this data as premium and monetized subscription features. PredictWind delivers both terrestrial and satellite AIS data on a zoomable map, while savvy navy displays terrestrial AIS data atop its in-app chart plotter.

While this data can be useful, it can’t be exported.

Enter PredictWind’s DataHub, a GPS tracking system that can collect internet AIS data from PredictWind’s servers using the vessel’s internet connection. DataHubs ($300, plus $50 for an NMEA cable) broadcast this data via Wi-Fi to networked devices and convert it into NMEA sentences that are shared with the vessel’s networks. This setup allows internet AIS data to be displayed on the vessel’s MFD alongside AIS-VHF data.

DataHubs can also act like terrestrial AIS stations, collecting the vessel’s networked AIS-VHF data, converting it from NMEA sentences to internet AIS data, and uploading it. Nick Olson, PredictWind’s marketing business development manager, says PredictWind shares this information for free with the internet.

DataHub users can select an internet AIS data range from 5 to 300 nautical miles. Olson says screen clutter isn’t problematic because targets scale in and scale out depending on the displayed zoom level (read: harbor versus offshore).

Luis Soltero, PredictWind’s DataHub developer, says that while a DataHub can’t graphically distinguish targets derived from internet AIS data with targets derived from AIS-VHF data onscreen, there are sometimes embedded clues that help identify internet AIS targets. For example, the call signs for all targets (Class A and both types of Class B) derived from internet AIS data are changed to read “DataHub.”

The Q Experience (see Yachting, November 2021) offers another option for displaying internet AIS data on an MFD with its Cloud AIS subscription-service feature. Here, the MFD manufacturer presents Pocket Mariner’s terrestrial AIS data (via a built-in SIM card) atop a chart plotter, which can also display AIS-VHF targets.

Latency can be a concern for all forms of internet AIS data. While AIS-VHF data is near real-time, internet AIS data—given its aggregate nature and the AIS bandwidth-sharing scheme, not to mention the distances involved—is older (ballpark 10 to 30 minutes or more). This means that onscreen targets derived from internet AIS data have moved. (A ship traveling at 18 knots covers 3.5 to 10.34 nautical miles in 10 to 30 minutes.) While some software applies dead reckoning and onscreen graphics to depict where the target could be, users are advised to check time-stamp and source data, and to cross-reference in-range targets against radar.

In all cases, AIS-VHF data should be trusted over internet AIS data, and satellite AIS data has inherent limitations.

“AIS satellite systems are incapable of receiving and/or processing all transmitted AIS position reports,” says Jorge Arroyo, a US Coast Guard program analyst who helps develop AIS regulations and standards. He adds that this is especially problematic in congested waters: “Many transmissions are usually garbled, but some providers are able to use algorithms to extract some data sufficient to provide a vessel track, but not necessarily the broadcast AIS message.”

Arroyo says the Coast Guard uses satellite AIS data, but cautions that long-distance AIS target shopping could be a distraction for recreational users. Additionally, he expresses concern about whether both kinds of AIS targets are easily distinguishable, and how they might affect the limited processing capabilities of onboard navigation systems.

So, will internet AIS data ever replace AIS-VHF or radar? No. But if you cruise with connectivity, are a disciplined watchkeeper, and are interested in gaining some bigger-picture awareness—albeit with large grains of sea salt involved—then internet AIS data could be an interesting and low-cost consideration.

I wouldn’t have minded having it sailing south from Alaska.

AIS Tech Specs

Class A AIS broadcasts at 12.5 watts every two to 10 seconds while underway. Class B-CS AIS broadcasts at 2 watts every 30 seconds; Class B-SO AIS transmits at 5 watts every five to 30 seconds. While interoperable, Class B-CS doesn’t interfere with Class A or Class B-SO signals, so opt for the latter.