The SS Pacific, a 223-foot side-wheel steamer, departed Victoria, British Columbia, on November 4, 1875, bound for San Francisco. Its cargo included gold and coal, the latter from a mine operated by the ship’s owners, as well as 275-plus passengers and 50-plus crewmembers.

Pacific encountered heavy weather as it steamed west out of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and then south past Washington’s Cape Flattery.

The crew aboard the northbound Orpheus, a 200-foot square-rigger, mistook Pacific’s masthead light for the Cape Flattery Lighthouse. The ships collided, damaging Orpheus’ rigging and—it’s believed—opening planks on Pacific’s hull. Frigid seawater likely swamped the hot boilers, triggering an explosion.

Some 325 souls were lost on that storm-tossed night. Only two people survived, making it one of the West Coast’s worst maritime disasters. Also, because Orpheus was navigationally blind, Pacific’s final resting spot was unknown.

In 1980, Jeff Hummel, then a student at the University of Washington, and Matt McCauley, Hummel’s high school buddy, recovered a World War II-era warplane from Seattle’s Lake Washington. They were sued, but they won the case and all salvage rights.

This is when Hummel heard about another group that was searching for Pacific, which he had known about, piquing his interest. “They eventually quit,” he says, adding that he thought it was a good project. “I just kept doing it.”

A marine-industry career—Nobeltec (now TimeZero), then Rose Point Navigation Systems—followed, but Hummel’s interest in the long-lost Pacific endured. In 2004, he purchased SeaBlazer, an 80-foot Desco trawler that he refitted to search for Pacific, and he again partnered with McCauley. The two founded the nonprofit Northwest Shipwreck Alliance and Rockfish Inc., their for-profit commercial salvage operation.

While numerous expeditions had searched for Pacific since 1985, Hummel says that Rockfish’s approach hinged on careful use of technology—including expertise in modifying off-the-shelf sonar equipment and building remotely operated vehicles—and key pieces of physical evidence.

Generations of commercial fishermen have scoured the waters off Cape Flattery, and they occasionally net artifacts, including chamber pots and coal. “The coal was really the key,” Hummel says, adding that because Pacific’s owners also operated a coal mine, he was able to send a sample to a laboratory to test against coal from the mine.

They matched.

The Rockfish team leveraged this information, coupled with fishermen’s GPS data, to reduce the search area from 338 square miles to just 2 square miles. While this was a huge reduction, technical sonar-imaging work remained. “It was an area that was difficult to search,” Hummel says.

That’s where technology, including their custom-built sonar, came into the picture.

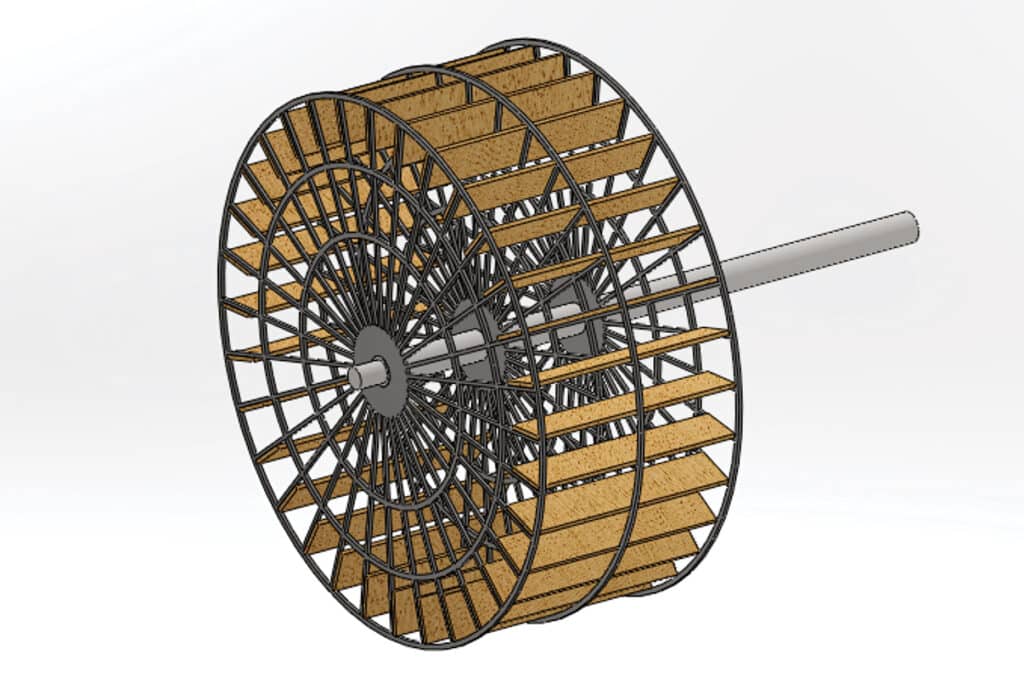

“We made our own transducers,” Hummel says, explaining that the team purchased off-the-shelf Simrad StructureScan transducers, chemically dissolved their potted encapsulating material, removed the piezoceramic elements and microprocessors, and then rebuilt them using “magic concrete” as the replacement encapsulating material. The result, he says, is transducers that can withstand far greater water-depth pressures than the originals.

The next step involved fitting these bespoke transducers into a towfish, which the team flew about 35 feet above the seafloor.

“We also developed our own robotics equipment,” Hummel says. This included two remotely operated vehicles—dubbed Falkor and Draco—that are equipped with Blueprint Subsea-built Oculus multibeam imaging sonars and that are capable of operating at depths down to 3,240 feet. “It’s kind of like having a radar on the robot,” Hummel says, adding that the ROVs were designed around these instruments. “We can find a beer bottle 100 feet away and drive the robot straight to it.”

The team also built a camera sled, which provides seafloor optics and collects artifacts via its rake.

The team leveraged ReefMaster software, plus SeaBlazer’s Garmin echo sounder, to create their own bathymetric charts. Critically, this software also allowed the team to create a points-of-interest database in real time as they scanned the bottom, so they could later revisit and evaluate.

This is how, after 12 search expeditions between 2017 and 2022, the Rockfish team identified their sunken needle in July 2022.

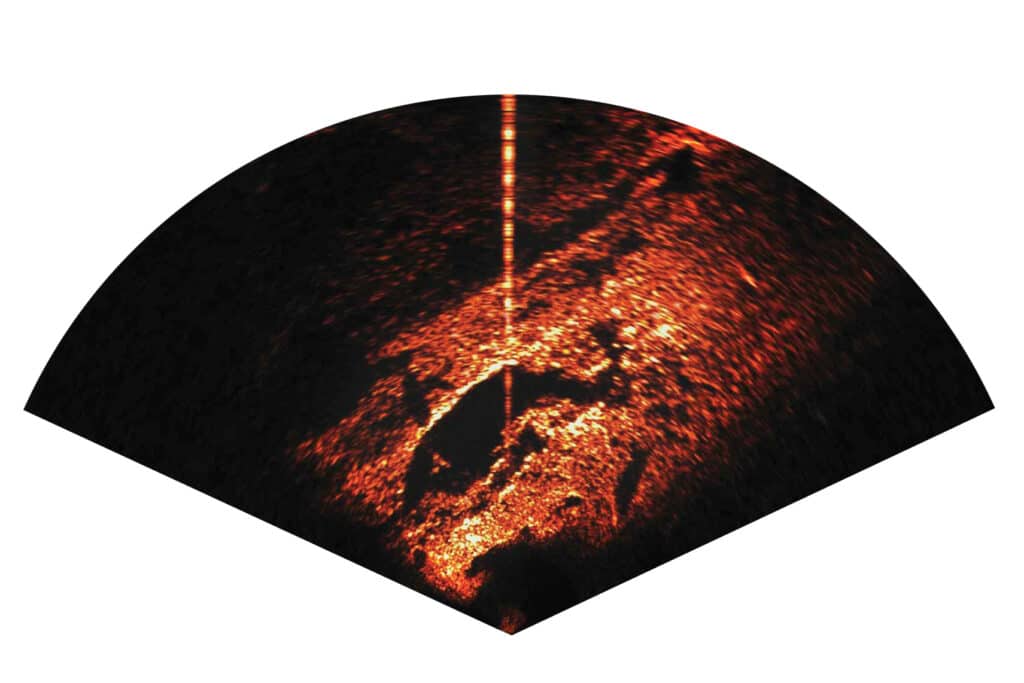

The first job was to comb the search area for points of interest using the towed sonar array. “It took a lot of convincing,” Hummel says of their first look at the wreck. “It wasn’t obvious at all.”

The image that convinced them that they had located their needle was of two circular seafloor depressions. These indents matched the 24-foot diameters of Pacific’s paddle wheels. “You’re not going to find two identical things on the bottom of the ocean,” Hummel says. “It has to be man-made.”

The team returned to the site aboard SeaBlazer, this time with two camera sleds and the ROVs. Once they ensured that the area was free of ROV-threatening snags, they dispatched Falkor to reimage the wreck with its Oculus sonar and to measure the hull’s timber spacing. “That matched up exactly to the timber spacing on Pacific,” Hummel says.

Finally, the team employed Falkor’s grabber arm to retrieve a piece of worm-eaten hull wood, and the camera sled’s rake to collect a chunk of a firebrick.

The team presented their findings and were granted salvage rights in November. Weather permitting, they’re planning numerous salvage expeditions this year.

Finding a long-lost ship isn’t a cheap venture, even if the incentives for finding it—including the gold that’s believed to have been aboard—are handsome. “So far, we have spent $2.1 million,” Hummel says. “We believe it will be a profitable venture. … The value of the wreck is substantial.”

Precious cargo will be sold, with funding being shared among Rockfish’s owners and Pacific’s underwriters. All salvaged cultural artifacts and personal belongings will be donated to a museum that the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance hopes to build in the Puget Sound area.

While Hummel may point to Rockfish’s use of digital and analog evidence as keys to finding Pacific, ultimately, the discovery also required a 40-plus-year friendship between two high school buddies who refused to give up.