When i recall childhood offshore adventures, certain objects come into focus: paper charts, parallel dividers, rulers, lorans, pencils and coffee mugs. My father used these then-mysterious-looking instruments to plot our position on a paper chart, which he backed up in our logbook. Flash-forward to 2015, however, and virtually all navigation is done on-screen via a multifunction display, allowing navigators instant access to a bevy of networked instrumentation and electronic cartography.

The world’s first peek at electronic navigation unfurled in 1984 when Giuseppe Carnevali, the CEO of Navionics, unveiled his Geonav electronic-chart display, but — perhaps because boaters were dismayed by the prospect of these Orwellian-looking devices sullying their helms — his revolutionary product encountered initial market resistance.

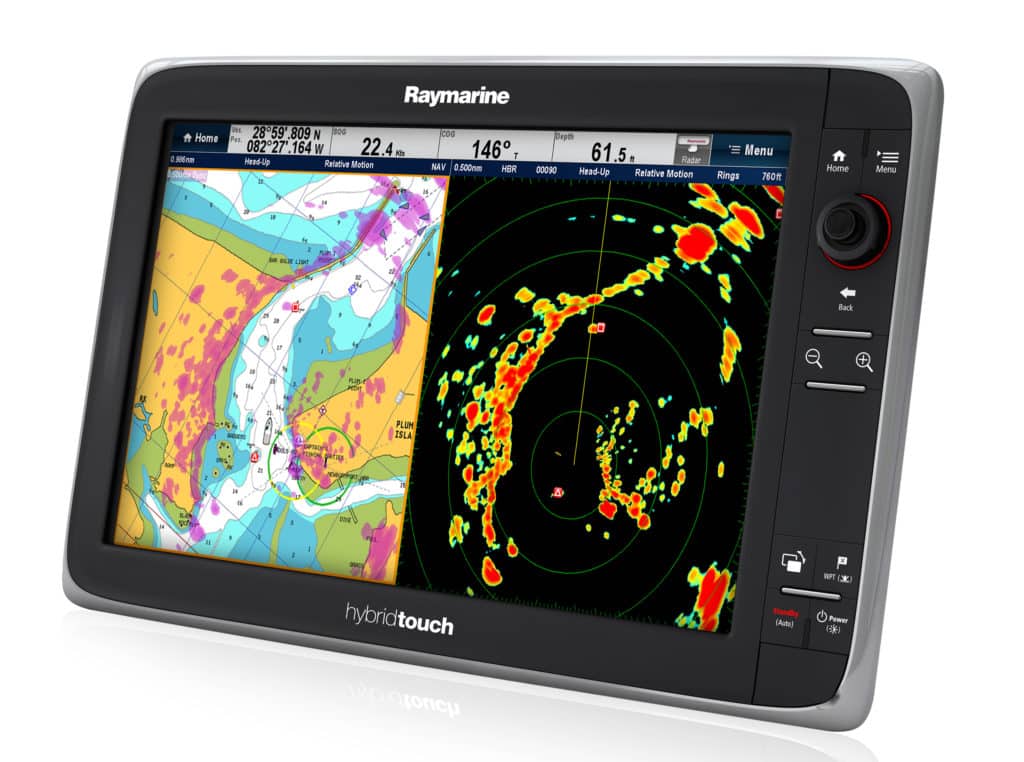

Fortunately, Carnevali’s idea paralleled the rise of the computer-electronics industry, and faster processors, bigger and less-expensive memory, and enhanced graphics spurred marine-electronics companies to innovate. Over time, simple chart plotters evolved into a brain for yachts, a trend that quickened with the introduction of GPS and networked-data backbones. Still, user interfaces (UI) were problematic, because multifunction display (MFD) operating systems (OS) weren’t intuitive. Enter the iPhone, with its touch-screen UI and philosophy that software should be user-friendly. Almost instantaneously, users became touch screen savvy, and marine-electronics manufacturers started leveraging this technology in multifunction displays.

“Integration is the new buzzword,” Dave Dunn, Garmin’s senior manager of marine sales and marketing, says about the differences between Garmin’s earlier offerings and its now-generation multifunction displays, such as the GPSMAP 7600 series ($1,499 to $5,499). Some examples include internal high-speed GPS and GLONASS antennas, sounders (CHIRP, traditional or proprietary technologies) and Wi-Fi.

Improved integration has let manufacturers streamline multifunction displays, but touch can sometimes be problematic in lumpy seas.

“Most people want touch,” says Eric Kunz, Furuno USA’s senior product manager, who adds that some customers still like a hard-button interface. For example, explains Kunz, remote keyboards help facilitate all-glass displays such as those on Furuno’s NavNet TZtouch2 multitouch multifunction displays ($3,995 to $5,995). Others agree.

“Touch is now a big part of our everyday lives,” says Steve Thomas, Simrad’s product line director, about the impact that wireless devices have had on now-generation multifunction displays, including Simrad’s NSS evo2 multifunction displays ($1,199 to $4,999).

This expectation has also shaped software development. “Customers want their MFD’s UI to be as easy to use as their smartphone,” says Jim McGowan, Raymarine’s marketing manager, about the company’s LightHouse II OS, which comes on Raymarine’s A Series ($799 to $3,199), eS Series ($1,099 to $3,649) and gS Series ($3,699 to $11,999) MFDs. “But it also has to be fast and responsive.”

UI aside, MFDs need high-quality charts to enable safe navigation. “MFDs used to come with just basic cartography, and most consumers would purchase more advanced [third-party charts],” says McGowan, adding that contemporary MFDs typically come bundled with high-quality cartography. Still, moving media onto the MFD must be simple. While manufacturers commonly allow users to download updates or purchases online, doing so requires an Internet connection. To bridge any gaps, manufacturers rely on internal drives for storing items such as base maps, the OS and manuals, as well as user-created media, while relying on microSD cards to import cartography or to back up files.

Also, says Kunz, years of relying on cloud-based storage services have trained customers to seek redundancy. “Customers want their waypoints to be password-protected, and they want cloud backups,” he says. When it comes to processing power, MFD processors historically lagged several generations astern of the personal computer market, but this has also changed. “In the past, manufacturers picked a processor for their MFDs, but the technology advanced so quickly it would only [remain relevant] for a few years,” McGowan says. “Today’s processors have a lot of overhead room. … We don’t want our MFDs to be bogged down in five years.”

Additionally, some manufacturers use application-specific integrated circuits to handle processor-heavy instrumentation. “[Hard-coded] chips crunch data quickly, and they bring the information over [to the main processor] on a specifically designed part of the board,” Kunz says.

The combination of data backbones, faster processors and improved UI has expanded the MFD’s onboard job description. Two prime examples involve autopilots and digital switching. While autopilots typically come with a dedicated control head, some manufacturers provide users with enhanced features when they network their yacht’s autopilot with its MFD (e.g., wireless pilot control).

Likewise, most contemporary MFDs now support digital switching. “Users can control their digital-switching system from their Simrad MFD, but the actual [digital-switching] black box lives elsewhere on the network,” Thomas says.

While careful mariners still carry a backup navigation kit, MFDs have usurped paper charts. About the only constant between the nav stations that I knew as a child and the ones that I frequent today are the coffee mugs, because the mariner’s age-old need to maintain a vigilant watch will never change.