Thanks to new technology and marine-focused manufacturing, the evolution of diesel outboards may finally be coming to a head.

When it comes to propelling larger boats, diesel as a fuel source wins against gasoline every time. But for many types of smaller boats with smaller motors, today’s lighter, faster-revving gasoline outboards make more sense. Many owners of diesel-powered yachts have tenders and toys that run on gasoline, which means carrying multiple fuels in multiple tanks, with the accompanying multiple challenges.

There should be, could be, would be a simple solution: diesel outboards. Yet diesel has never caught on in the outboard market, and with few exceptions, it hasn’t been an option.

Until now.

Not one, but two manufacturers are introducing high-horsepower engines — the Cox and the Oxe — that not only run on diesel fuel, but that also are designed or redesigned for use as outboards. Both have relatively large sizes (300 hp for the Cox and 150 to 300 hp for the Oxe, with the larger models under development), and both utilize new technology to meet modern emissions standards while providing weights and sizes acceptable for use on modern boats.

Power Play

While superyacht owners with gas-powered tenders should benefit from these developments, the drivers for the diesel outboard market are not recreational boaters. Instead, they’re military and commercial buyers.

“You can throw it from full forward to full reverse without breaking anything.” — Stosh Sheldon, Oxe dealer

“The military needs single-source fueling,” says Kerry Thompson of Mack Boring’s Commercial Marine Group, the East Coast distributor of Oxe diesels (which are built in Sweden). “And the incredibly long service hours and efficiency the Oxe provides is also very attractive to commercial outfits. We expect the vast majority of these engines to go into military or commercial use. But there will naturally be some recreational applications, including yacht tenders, for which these engines are ideal.”

Cox sales director Joel Reid says his company expects about 75 percent of sales to be for commercial or government use.

“But the niche is there for recreational use as well,” he says. “It’s already accepted in Europe, and while there’s a different cultural environment in the United States, we can fill needs that aren’t currently being met.”

As another example of diesel’s recreational applications, Reid points to saltwater fishermen, who always seem to make longer and longer runs to ever more distant fishing grounds.

“We can offer about 25 percent better efficiency, extending their range,” he says. “And you can expect about three times the life span of an average current gasoline outboard. To meet the market’s needs, we’re using gear ratios that can mimic gas-engine rpm at the propeller, and we can package the engines in ways that are familiar to boaters, using things like off-the-shelf SeaStar controls and Optimus systems.”

A New Species

Diesel Development

Cox and Oxe took different paths in developing the technology behind these diesel outboards.

In the case of the Cox, built in the United Kingdom, the powerhead was purpose-built for use as an outboard engine. Design and development costs used to prevent taking this approach, and most of the players who have floated diesel outboards in the past have instead modified existing platforms. Mercury Racing, for example, offers a diesel-fueled but spark-ignited DFI two-stroke that reportedly shares 95 percent of its components with the gasoline engine it’s derived from. And that engine is for government sale only. Yanmar, which sold small outboard diesels in the United States years ago, is distributing (in foreign markets only) a 50 hp German-built model derived from a diesel motorcycle power plant. EPA approval of this outboard is pending, and Yanmar hopes to bring it stateside soon.

By starting from scratch rather than modifying an existing platform, Cox was able to design the engine with a vertical orientation — solving a lot of problems associated with transferring power from a horizontal crankshaft down to a lower unit’s propeller. While this strategy eliminates multiuse applications, and is thus unattractive to larger corporations making diesels that can power anything from generators to construction equipment, it’s ideal for an outboard.

“And you can expect about three times the life span of an average current gasoline outboard.” — Joel Reid, Cox sales director

“Add in common-rail technology and the use of EGR [exhaust gas recirculation] and we can meet emissions requirements easily while providing all the advantages of diesel in an outboard package,” Reid says.

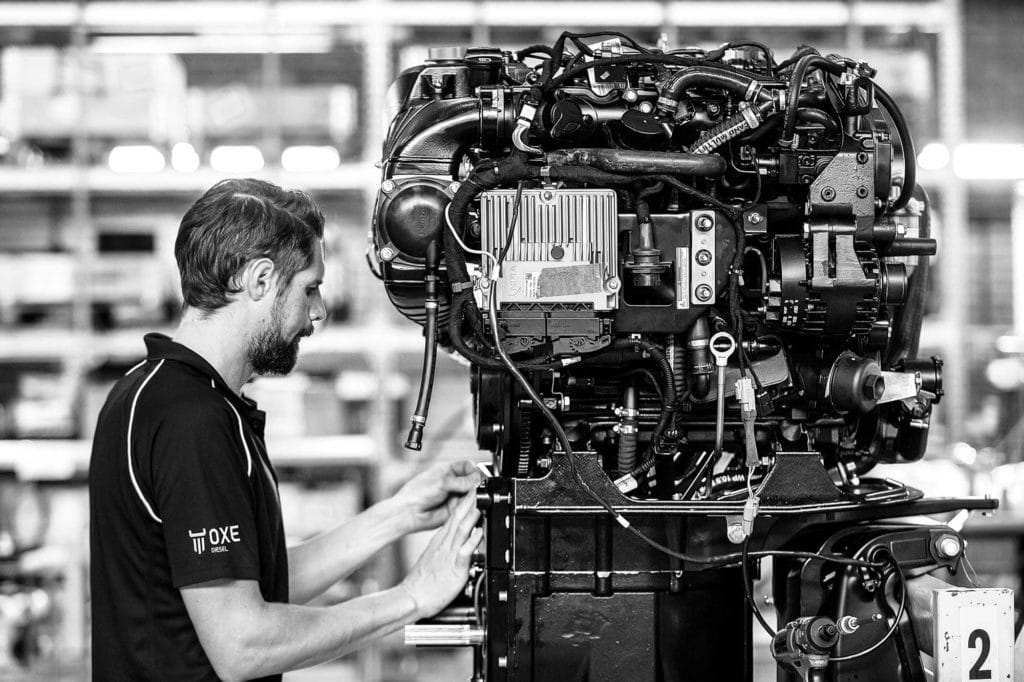

Oxe, on the other hand, starts building its engines from a GM block that is marinized with heat exchangers, an intercooler, an oil cooler, and service points shifted to the front for easier access. Again, Oxe uses common-rail technology as a key feature, but the usual challenge to putting an automotive block into an outboard package remains: how to transfer the power from a horizontal orientation down to the propeller.

Oxe resolves that challenge with a belt drive.

“There are a number of advantages we get from the belt drive,” says Stosh Sheldon of Shore Power Solutions, Oxe’s dealer and service center in Grasonville, Maryland. “It’s durable [Oxe claims a 1,000-hour service life between belt changes], we can adjust it to change the gear ratio [1.73-to-1 or 2.17-to-1] and, unlike regular outboards, crash stops aren’t a problem. You can throw it from full forward to full reverse without breaking anything.”

Will these new diesel outboard options replace gasoline outboards in the recreational market? Not a chance. Even the biggest diesel proponents recognize this.

As Cox’s Reid says: “We’re not trying to convince people to give up their gas. We’re just going to give them some new options.”

Inside the Oxe

The Oxe (above) is horizontally oriented, a design feature shared by very few outboards. Power is transferred via a belt drive, a unique approach that’s distinctly different from the also horizontal Seven Marine gasoline outboards, which are similarly based on a GM block, in their case the LSA Gen4 V-8.

Safety Matters

One of the major reasons the government wants single-source diesel fueling — and a good reason for tender owners to want it — is safety. The much lower flashpoint of gasoline means that a spark anywhere in its vicinity can lead to disaster, whereas diesel fuel normally requires compression to ignite. Diesel exhaust also produces much less carbon monoxide, and while the sulfur dioxide it emits can be unpleasant, it generally isn’t life-threatening.

Weighty Debate

Weight on these new outboards, always a significant issue with diesel power plants, is still well above that of gasoline outboards — but not so much as to be a deal killer.

The Cox CXO300 tips the scales at 826 pounds, while 300 hp gasoline outboards range from around 550 to 650 pounds. With many of today’s outboard boats being designed for relatively heavy power plants, these engines are in the ballpark. As a point of reference, many inboard diesels with about as much power weigh more than 1,000 pounds.

Oxe’s 200 hp diesel, meanwhile, is 770 pounds. Since its 300 hp version is still under development (sales may start in 2020), exact specifications aren’t yet available.

What about bulk? I saw a pair of Cox 300s mounted on an Intrepid 345 Nomad and, visually, they looked right at home.