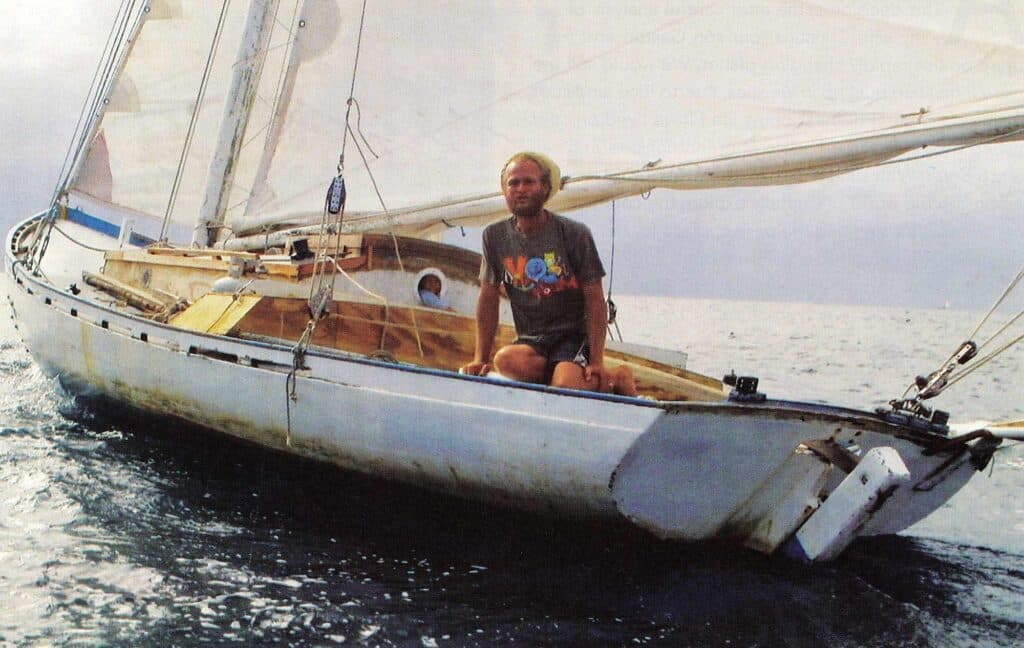

The voyage was a ludicrous proposition from the outset, and, in retrospect, there was only one way it could’ve ended: tragically. In July 1991, a well-known and controversial cruising sailor named Peter Tangvald set sail from the Spanish Virgin Island of Culebra southbound for Bonaire, ostensibly to safely negotiate the onset of hurricane season. Joining Tangvald aboard his engineless 50-foot cutter was his 7-year-old daughter, Carmen, but the kooky part of the enterprise was the towline to the leaky 22-foot sailboat trailing astern, commanded by his 14-year-old son, Thomas. The elder Tangvald had decreed that the boy stay aboard the smaller vessel to bail it out along the way so it wouldn’t sink beneath him. Neither boat carried a VHF radio; there was no way to communicate beyond waving and hollering.

Four days into the trip, on a dark night off the windward reefs of Bonaire, Thomas came on deck just in time to watch in horror as his father’s boat careened into the shallows along the surf line. He was barely able to scramble onto his surfboard before his own craft crashed into splinters. Neither his dad nor his sister survived the wreck, but, after six hours, Thomas made it ashore.

All of this is the opening scene in marine journalist Charles J. Doane’s new book, The Boy Who Fell to Shore: The Extraordinary Life and Mysterious Disappearance of Thomas Thor Tangvald. The title is a nod to the 1976 sci-fi movie The Man Who Fell to Earth, which is about an alien who crash-lands in New Mexico and experiences incredible success and debilitating failure. David Bowie was the film’s fall guy, just as Thomas is the protagonist in Doane’s story. Each of them suffers a similar fate.

Tragedy was nothing new to the Tangvald clan. Twice, Peter Tangvald had sailed over the horizon with young wives who never made it back, and, in the cruising community, there were loud whispers that he had plenty to do with their disappearances. Thomas was born and raised at sea, and one of the women who went missing was his mother.

Read More: Silent Running

After falling ashore himself, Thomas was whisked away by old cruising mates of his father’s, who’d been recruited for the task in the event anything happened to the elder Tangvald. Thomas was taken to the mountains of Andorra. For Thomas, who’d lived his entire life in the tropics, it was as incredible and bizarre as anything Bowie’s alien encountered in the desert. Remarkably, at least at first, he thrived. Though he had no true education whatsoever, beyond the books about science and naval architecture aboard his father’s boats that he devoured, he possessed a genius-level IQ. After two years’ worth of studies crammed into one so he could attend college in Great Britain, he enrolled at the University of Leeds to study advanced mathematics and fluid dynamics. He seemed bound for a far-different path from that of his father.

Except that, like his old man, he was always drawn back to the ocean. In the same vein, at this juncture, Doane’s narrative also returns to the sea. Many boats are involved, as are copious helpings of drugs and alcohol. Women come and go; kids are sired. In many unfortunate ways, as far as family men go, Thomas was a chip off the old block.

And yet Thomas is not unsympathetic; he’s even a compassionate character. His core values, his love and respect for nature and the islands, and his hopes and strivings are all solid. He was a hell of a seaman, that’s for sure. Which makes the disappearance that concludes this tale a mystery indeed.