Two weeks before Christmas, when most Americans were ready to relax with friends and family, the U.S. Coast Guard command center sprang into urgent action. The 30-foot Catalina Atrevida II was not where it was supposed to be. Sixty-four-year-old Kevin Hyde, 76-year-old Joe DiTomasso and his dog Minnie had left Cape May, New Jersey, on November 27 for a cruise to Marathon, Florida. For a while, everything went fine. According to news reports, DiTomasso was known for losing his phone, so his family didn’t worry after the men left North Carolina on December 3 and then went silent.

But by December 11, that quiet was deafening. The US Coast Guard Fifth District Command Center in the mid-Atlantic was notified. Rescuers immediately issued urgent alerts and reached out to commercial vessels in the search area. Multiple aircraft and cutters were launched; vessels from the US Navy’s Second Fleet started searching.

By the time a tanker crew spotted the Atrevida II more than 200 miles off the Delaware coast, 10 days had passed. The boat was dismasted. The men were exhausted. They had no fuel or power. All their radios and navigation equipment were dead.

What likely saved their lives was the fact that they were waving a green flag—pretty much their only remaining option.

The Human Factor

Kevin Ferrie knows stories like this one all too well. He’s a retired US Coast Guard commander who now serves as a civilian with the US Coast Guard Office of Auxiliary Boating & Safety.

“The majority of accidents that are in our database—the root cause is human factors. Somebody did something or made a poor judgment call,” he says.

Ferrie knows what’s behind those statistics on a level that most boaters never will. He also provides shore-side support for the annual Salty Dawg regattas that guide groups of sailors down the East Coast to the Caribbean and back. And he’s a long-distance cruiser himself, having sailed from Maine to the Caribbean aboard a 45-foot Jeanneau with his wife, their four kids and a pair of Labrador retrievers. He once found himself in a situation where his autopilot broke, and he needed to use an Iridium Go! as well as a Garmin inReach to communicate with shore-side help. He didn’t need 10 days to start losing his mind; disorientation from trying to fix the autopilot hit him in a day and a half.

“It was in the lazarette. I had to pull out all this gear to get to it and contort my body in all kinds of ways,” he says. “Off and on, it took me like 36 hours to fix it, including communicating offshore and waiting for responses. I was exhausted.”

All his experiences have taught him one overarching lesson about offshore cruising: Preparation is key. “The minimum federal safety standards are important: You need your life jackets, your distress signals, your VHF radio,” he says. “But that’s really baseline. If you’re heading offshore, it’s not enough.”

Communications

In terms of offshore preparation, communications technology that lets boaters summon help includes everything from cellphones and VHF radios to personal locator beacons and EPIRBs. Having as many types of communication as possible available is key, he says, because, in a lot of cases, simply being able to call for instructions or help can stop a bad situation from escalating into a dangerous one.

One recent example he encountered was with a vessel that lost its rudder this past fall off the East Coast. The husband and wife who were aboard set off their EPIRB and used their Garmin inReach to communicate with the Coast Guard and shore-side support.

What the couple initially feared was an emergency became a solvable problem because they were able to communicate, and because they knew other people were keeping track of them.

“At first, they were like, ‘Oh, my God,’ and we had to help them get through that mental problem,” Ferrie says. “Ultimately, they ended up with the Coast Guard arriving on scene and towing them in. But with help, they were able to make way toward the coast and rendezvous for help. They had the communication devices and the spares. They needed somebody to say, ‘It’s OK. You’re prepared for this.’”

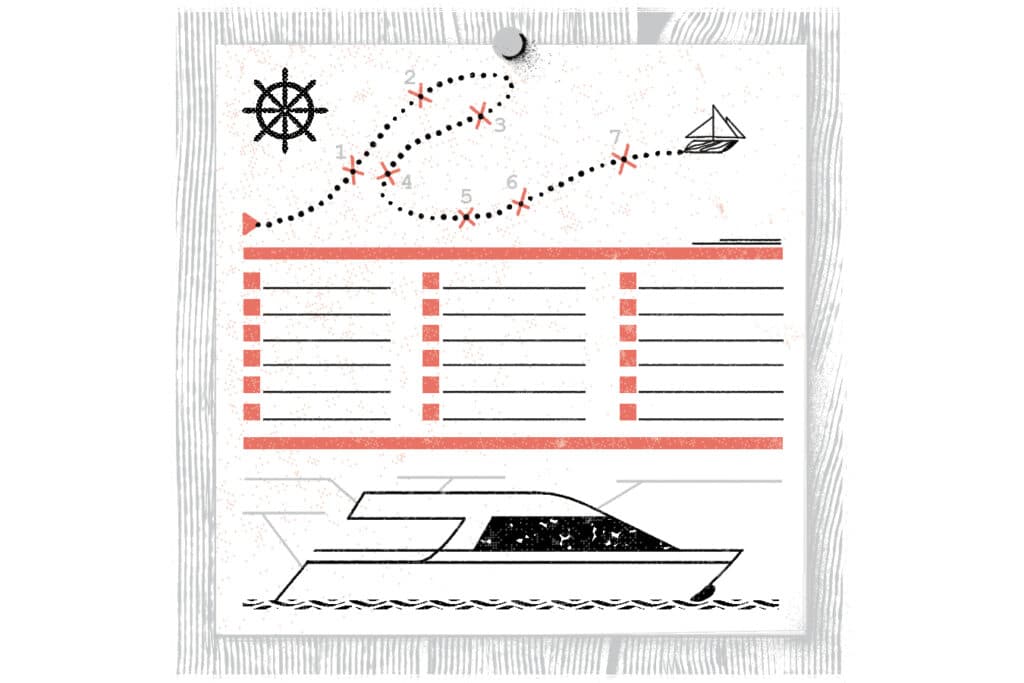

The Float Plan

Next on Ferrie’s list of important preparations for offshore cruising is filing a float plan. The US Coast Guard has a float-plan form online—for free—that boaters can download, fill out and leave with a responsible person ashore. It includes details such as the boat’s make and model, and the types of communication devices on board, and details about where the boaters expect to be, and when—all information that rescuers will need if the boat doesn’t show up where it should be.

In the case of the Atrevida II, family realizing the boat was overdue was a key component in the search efforts. That information is the essence of what makes filing a float plan such an important step in the offshore-cruising process. A float plan can sometimes be a boater’s only way to “signal” for help if an onboard emergency develops quickly.

“In a fast situation, the float plan is incredibly important because you may not even have time to make the mayday call,” Ferrie says. “Fire can happen really quickly on a boat. It can block access to everything except your way overboard.”

Shore-Side Support

Having designated shore-side support people is different from filing a float plan. With shore-side support, a boater has volunteers or paid professionals helping to keep an eye on their course and anything happening around them, including developing weather systems.

“It’s more of an active person that’s watching out for your best interests,” Ferrie says. “With shore-side support, they’d be proactive and reach out to you. They’d say, ‘Hey, did you know this? Are you watching the weather? This is what I’m seeing heading your way in 12 hours.’”

Having shore-side support in place keeps everyone’s mind at ease both on the boat and ashore, he adds. During the Salty Dawg rallies, boaters are required to check in with the shore-side support teams at fixed intervals. Everybody involved knows that as the boats are making their way down the Atlantic coast, a failure to check in means something has gone wrong. For a boater having an emergency offshore with no other way to communicate, simply knowing that shore-side support people will take action can make all the difference between staying calm and panicking, which makes the onboard situation worse.

Safety Gear

Buying a bunch of top-notch safety gear and loading it onto the boat is not enough, Ferrie says. All the gear in the world won’t do a boater any good if he doesn’t know how to use it. “If you just buy a life raft, but you don’t know how to deploy it or what’s in it, that’s bad money spent,” he says.

Life jackets are a hugely important safety-gear requirement. According to the US Coast Guard’s most recent boating-accident data, 81 percent of fatal boating accidents involved people drowning, and some 83 percent of those victims were not wearing life jackets.

“Offshore, you should always wear a life jacket, and, with the inflatable designs, there’s no excuse about comfort anymore,” Ferrie says, adding that for sailors, “you also should always be attached to the boat. Run jacklines from the stern to the bow and clip your life jacket into them.”

He also thinks of communication devices as a form of safety gear, if boaters understand what each device on board can, and cannot, do.

“A personal locator beacon is basically an EPIRB for a person,” Ferrie says. “It will alert the authorities that there’s an emergency. But there’s also an AIS MOB beacon that alarms any boats in the area with AIS and gives them the position. So if you went overboard at night and the crew were sleeping, a personal locator beacon would not alert the crew, but an AIS MOB would wake them up.”

As for life rafts, they’re not required for offshore passages, but Ferrie highly recommends having one on board. He urges boaters to take advantage of the opportunities that come with every life raft’s required service intervals, which are a great time to learn how that particular piece of safety gear works.

“If your life raft is due for a service, talk to the service company, and be there when they open your raft,” he says. “Examine the raft. Visit the facility, and understand what rations come in the raft. Do you need more emergency rations? A ditch bag? You need to prepare that, and it depends on where you’re sailing. A coastal hop down the East Coast of the US is a lot different from a 30-day passage to the South Pacific. You have to think about how long it might take for people to find you.”

Spare Parts

When Ferrie thinks about spares, his mind takes him to places well beyond parts and tools. Yes, those things are important, but he thinks about spare everything—including food, water and fuel—because in an extended emergency, a boater may need more than a 10 percent reserve of all three.

Carrying extra water is a must, he adds, because human beings can survive without food for a while, but not without water.

“Water tanks offshore can get contaminated in rough weather if you have saltwater intrusion,” he says. “Don’t count on being able to make water in a rough sea state. Have some water in five-gallon jugs.”

Many decisions about which spare parts and tools to stow boil down to the individual vessel and what its critical points of failure could be. “A lot of it’s in steering gear, the halyards if you’re sailing, fuel filters. If it’s rough, you may stir up sediment in your tank, and if you do that, you’ll have clogged filters,” Ferrie says. “You need to know how to fix that and have the critical spares on board.”

Crew Endurance

Having enough crew so that everyone can be focused on-watch and resting off-watch is also “a huge one” that Ferrie thinks about in terms of preparations. If whoever is at the helm is exhausted when something goes wrong, the odds skyrocket of a solvable problem getting worse.

“There’s a saying: People typically break before the boats do,” he says. “At some point in a heightened-stress situation, it becomes a mental game.”

He adds that boaters should never, ever get themselves into a situation where they will feel forced to arrive at or depart from a certain location on a specific day or at a specific time, for any reason.

“You need to understand the weather,” he adds. “There’s a saying in cruising: If you have visitors coming, you can pick the location or the time, but you can’t pick both. When you’re forced into a schedule, you tend to make poor decisions. You feel like, ‘I have to get to this island because my mom’s going to arrive.’ Be patient, and wait for the weather window that suits your skills and ability and your boat.”

Take Classes

Another key piece of advice is to take boater-education courses. Many people wrongly assume that only beginners need classes; in fact, every page of this article includes a sidebar about advanced classes available for powerboaters and sailors alike. Classes can be taken nationwide, not only for offshore route-planning and passagemaking, but also for gaining a detailed understanding of how communication devices and mechanical systems work.

Everything a boat owner learns in those classes can be passed along to other crew members, including those who join a passage only for a short leg at a time.

“Think through possible worst-case scenarios and how you would respond to them,” Ferrie says. “Do that as an exercise with your crew. What would you do in a man-overboard situation? Do they know to stop and stare and point at the person?”

Yes, simply being able to keep eyes on a boater in trouble can sometimes make all the difference, as it did for the Atrevida II. After the tanker crew spotted the sailboat’s waving green flag, both the men and Minnie the dog were able to get aboard the tanker and hitch a ride back to New York. The men were exhausted and beaten up from the weather. They were taken to a hospital for observation to make sure they didn’t have hypothermia. One described his legs as feeling like rubber from trying to stay upright for so long.

But they both lived to tell their tale, just like the more than 75,000 people the Coast Guard Office of Auxiliary Boating & Safety has saved during the decades since its inception. And in a bad situation, that’s the statistic any offshore boater ultimately wants to be.

Learn the Basics

America’s Boating Club (previously known as the US Power Squadrons) offers an entry-level course for beginners who want to learn the basics of everything from navigation to safety equipment. This course also meets most states’ boater-safety education requirements.

Add New Skills

Boaters who complete the America’s Boating Club basic class can move on to higher-level courses. One course focuses on offshore navigation, with lessons in things like celestial navigation as a backup in case GPS equipment fails beyond the sight of land (and landmarks that can be used to navigate back home). This course also covers ways to set offshore navigational routines.

Cruise Planning

Another class that America’s Boating Club offers is focused on cruise planning. It covers how to plan a longer-term itinerary, as well as equipment the boater may need, key safety gear, crew training, communications, dealing with weather, handling emergencies and tips for cruising outside the United States.

Teaching the Tech

Yet another class that America’s Boating Club offers focuses exclusively on marine communication systems. It helps students understand the differences between VHF radio, the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System, radiotelephones, long-range communication systems and other technology that can help keep offshore boaters in contact with civilization.

For Sailors

The American Sailing Association has more than 300 schools across the United States as well as locations in other countries. After passing the basic keelboat sailing class, boaters can advance to basic coastal cruising, which teaches lessons focused on operating a boat during the daytime with wind conditions up to 20 knots.

Advanced Sailing

Upper-level classes from the American Sailing Association include advanced coastal cruising and offshore passagemaking. The passagemaking class is designed for boaters who want to sail extended offshore itineraries that will require celestial navigation. Sail repair, offshore first aid, abandon-ship protocols and other skills are also part of this course.

It All Comes Down To Preparation

“The minimum federal safety standards are important: You need your life jackets, your distress signals, your VHF radio. But that’s really baseline. If you’re heading offshore, it’s not enough.”

Basic Problems To Avoid

According to US Coast Guard accident data, top problems include operator inattention, improper lookout and excessive speed.

Main Types Of Boating Accidents

The US Coast Guard’s top five are collisions with other boats, collisions with fixed objects, flooding/swamping, grounding and falls overboard.

Watch The Weather

The US Coast Guard’s top 10 factors contributing to accidents include weather, which killed 30 people in the most-recent-year statistics available.

Being Offshore Is Different

The US Coast Guard’s most recent data shows that more boating accidents happen offshore in the Atlantic Ocean than in any single state.