Watching without wincing is impossible. In the video, which went viral over the summer, a floatplane and a boat are on a collision course off the coast of Vancouver. People are filming from multiple angles on shore, with massive cruise ships looming in the background.

It’s a flat-calm day in the harbor. There’s clear visibility. The DHC-2 MK I Beaver, operated by Harbour Air Limited, has a pilot and five sightseeing passengers aboard. It’s on a takeoff run, accelerating with every second.

The boat is on the smaller side, likely used for day trips, possibly without a VHF radio or other helm electronics. It’s carrying a skipper and seven guests, and is moving fast enough to throw just a small wake—which is sometimes the only thing a seaplane operator can see, since the plane’s nose or wings can obscure the boats themselves.

Neither the plane nor the boat slows down. There are no discernible attempts by the pilot or the skipper to alter course.

The collision—which looks as if the seaplane is using the boat as a ski jump—tears the canvas top off the vessel. It rips the floats from the bottom of the plane, which then begins to sink.

Everybody on the plane is uninjured. Two of the boaters end up at the hospital.

It’s unclear whether the boaters were aware of the approaching plane or knew they were in a designated seaplane zone on the local charts, but an audio recording from the control tower reveals that the plane’s pilot was alerted to the boat’s presence.

One question, and one question only, dominated the online debate in the days and weeks that followed: Whose fault was it? Pilots insisted the boat’s skipper was to blame. Boaters were sure that the seaplane should have given way.

Experts say that the rules of the road are one thing on paper, but in reality it doesn’t matter. Everybody needs to do a much better job of paying attention out there.

A litany of rules can apply in a situation like this one. In American waters, according to the US Coast Guard, they might include Rules 6 through 10, as well as Rules 13 and 18. Rule 18, titled Responsibilities Between Vessels, notes the obligation of seaplanes: “A seaplane on the water shall, in general, keep well clear of all vessels and avoid impeding their navigation,” including during takeoff and landing.

In Canadian waters, according to Transport Canada, Rules 5, 7 and 8 would likely apply. They say that if there is a risk of collision, “operators are to take early and immediate action” to avoid it. This rule applies even if the vessel has the right of way.

It is indeed possible to read these rules as a kind of Rorschach test, using them to support whichever argument a pilot or a skipper wants to make—but at the end of the day, everybody is responsible for doing everything possible to avoid a collision.

“As a boater, you must be aware of what is going on around you, both on the water and in the sky at all times,” Sau Sau Liu, a spokeswoman for Transport Canada, told Yachting. “Watch for aircraft anytime you are out on the water, and give them plenty of space. When seaplanes are landing or taking off on the water, they have little or no ability to alter their course. Attempting to do so may cause the seaplane to capsize.”

During takeoffs and landings, she adds, a seaplane is considered restricted in its ability to maneuver and unable to keep out of the way of other vessels. “In these situations, boat operators need to be aware and to take action to avoid a collision by changing their path of travel, and reducing their speed to avoid a collision,” she says.

Ann Einboden, education officer for America’s Boating Club of the San Juan Islands in the Pacific Northwest—where seaplane takeoffs and landings are frequent during the prime boating months—says boaters who take an education class are taught the priority of vessels in terms of who has the right of way. Floatplanes, she says, “are at the bottom of the list with the least priority, but we tell people to make them a high priority.”

The reason, she says, is that when seaplanes have their floats on the water, they have a fair amount of maneuverability. However, during takeoffs and landings, the planes need a much wider berth. “We treat them like they’re a tanker,” she says. “Everybody gets out of their way so they can have a clean landing or a clean takeoff.”

In the Florida Keys, another hotspot for seaplane activity, Keys Seaplanes owner Nick Pontecorvo says that while seaplane zones are on maritime charts, they’re less precise than, say, channel markers. “Seaplanes always want to try to take off and land into the wind, so it’s not really a runway that has a definitive start and a definitive end,” says Pontecorvo, who has been flying seaplanes since 1997. “I’ve gone to Little Palm Island close to 7,000 times, and I don’t think I’ve done the same takeoff and landing even twice.”

It’s a fairly regular occurrence, he says, to have boats or personal watercraft interfere with a plane’s takeoff run. Sometimes, he says, a skipper isn’t paying attention, but other times, it’s intentional, such as with people on personal watercraft attempting to race the seaplanes.

“These guys are idiots. It’s a special brand of stupid to race a seaplane,” he says. “They’ll come up on my right side, which is my blind side, and they can accelerate a lot faster than I do, so they’ll cut in front of me. The first one isn’t such a big deal, but if I hit a wake, the seaplane can turn 10 degrees in a matter of feet.”

Often, he says, a second PWC rider is nearby—filming the race for posterity—and is suddenly on a crash course with the plane.

“I’ve had to deviate from my takeoff run or shut it down thousands of times,” he says. “Once you’re about a third of the way through the takeoff run, you start getting more control, but I’ve had to change my course or stop the takeoff run because of boats in the way.”

Einboden says that unlike recreational boaters, seaplane pilots are licensed and tested yearly. “They’re following the rules, but they can’t adjust for some idiot that just zooms in front of them,” she says, adding that skippers failing to look around is a far more common problem. “The Coast Guard says every single year that the number-one reason for accidents and fatalities at sea is situational unawareness,” she says. “That’s operator error. It means nobody is paying attention.”

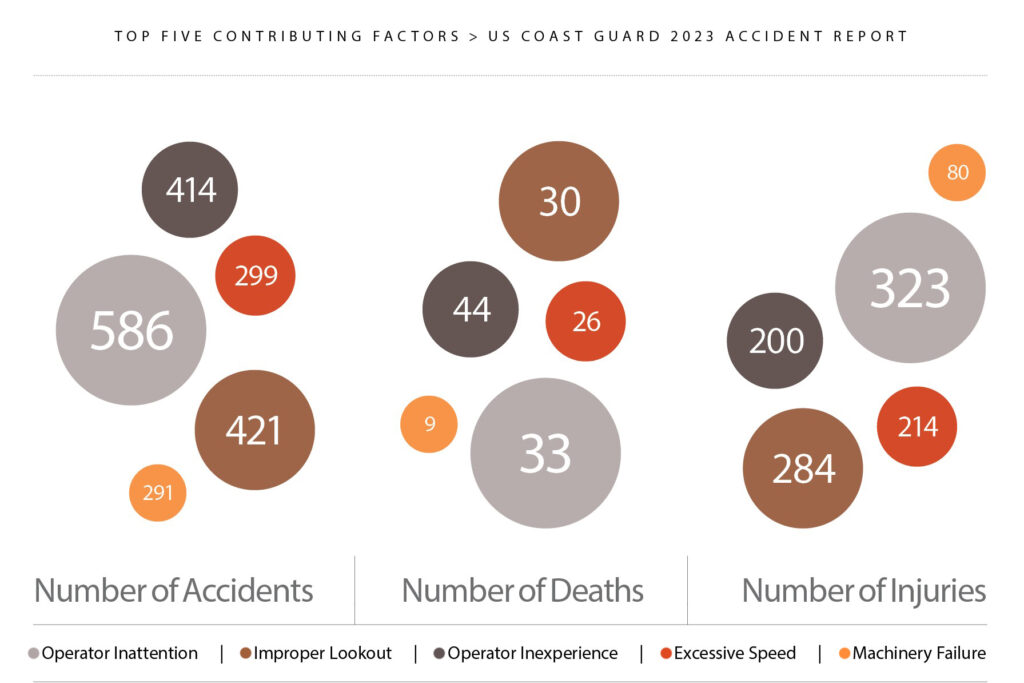

Indeed, according to the most recent data available from the Coast Guard, the top three contributing factors to accidents are operator inattention, improper lookout and operator inexperience. Those causes dwarf things like weather and equipment failure when it comes to boaters getting injured or killed.

The good news is that the waters were safer in 2023 than in 2022, with fatalities down by more than 11 percent and overall incidents down by nearly 5 percent. Nonfatal injuries also declined last year.

And it’s important to note that seaplanes and boats don’t crash too often, in Canada or the United States. The Vancouver Sun reported that the collision over the summer was the first in that busy harbor in a quarter century.

Still, in its annual report, the US Coast Guard describes the exact conditions that were present that day: “Boaters should remain vigilant on the water as most incidents occur when you might least expect them—in good visibility, calm waters and little wind,” Capt. Amy Beach, inspections and compliance director, states in the report. “The most frequent events involve collisions with other vessels, objects or groundings, which is why it is so important to keep a proper lookout, navigate at a safe speed, adhere to navigation rules and obey navigation aids.”

Indeed, the advice Pontecorvo gives his seaplane students applies to boaters too. “Every plane is equipped with a very good anticollision device,” he tells them. “It’s called a window. Use it.”

Busy Areas

According to the Seaplane Pilots Association, there are more seaplanes in Florida than in any other state. Anchorage, Alaska, is home to the largest seaplane base in the world, with more than 750 resident aircraft and 67,000 operations annually. Most of them remove their floats and replace them with skis so they can stay in use during the winter months.

Prior Crashes

The Times Colonist reported that this summer’s Vancouver collision was just the third in all of British Columbia in the past 25 years. The most recent crash between a boat and a seaplane in Vancouver’s harbor was in 1999. According to The Vancouver Sun, the 1999 incident involved a boat that was struck by a floatplane as it tried to land. One boater was hospitalized. No plane passengers were injured.

Take a class

The Coast Guard says 75 percent of boating deaths in 2023 occurred when skippers had no boating safety instruction.