Blazing the Trail

I was reminiscing recently with my old friend and former design client, Ken Denison, about the “golden age” of motoryacht construction. Not the big boom that bombed in the 1920s, but the surge of the last 20 years. The seeds for this boom were sewn in the 1980s and much of the banging and sawing was coming from Broward Marine’s yards in Michigan and Florida. Ken’s parents, Frank and Gertrude, created Broward and it was at the eye of a “perfect storm” when baby boomers, the economy, and technology collided. In the 1980s, Broward delivered more than 80 boats over 80 feet and when the yard’s ads suggested “It must be a Broward,” it likely was.

The Great Depression knocked the wind out of yachting, but enthusiasts held out for better times or downsized. World War II brought government contracts, and with the war’s end came a revitalized market for more modest coastal cruisers. American yacht builders Trumpy and Grebe continued to work in wood, while Burger shifted from wood to steel. The average size of motoryachts inched up. However, by the early 1960s, the typical flush-deck houseboat or cruiser-style yacht still measured about 60 feet.

In 1948, Frank Denison purchased Dooley’s Dry Dock on the New River in Ft. Lauderdale, while on honeymoon with his wife, Gertrude. He renamed the yard Broward Marine, a nod to its location in Broward County. Frank had grown up near the water in Michigan and at age 13 served as cabin boy on a 300-foot lake steamer. As a young man, he built a trucking business, but his dream was to build boats. Shortly after the purchase of Dooley’s, Frank bid on the construction of a dozen 146-foot and 172-foot minesweepers. “Mom and Dad drove to Washington to deliver the bid package personally,” said Ken. “Mom typed the final details in the back seat of the car and Dad raced up the stairs of the Navy Procurement office, just beating the deadline.”

Ft. Lauderdale locals referred to Broward’s first project as “Denison’s folly,” believing it was impossible to get such large vessels down the New River. Frank built the hulls at the Broward yard and floated them downriver to Port Everglades, where he added the superstructures and armaments. He launched a minesweeper every 90 days and soon Broward Marine became the largest private employer in Broward County. “Dad was a production genius,” said Ken. “Anybody that ever worked with him would tell you that he took little interest in a boat after it was launched—his passion was getting the boat in the water.”

Broward’s first yacht commission came in 1954. Built for $500,000, the 96-foot Alisa V was the largest motoryacht launched in the U.S. in decades, according to Time Magazine. “She had a powder-blue hull and a bright red bootstripe and trim—she was a shocker for the blue blazer set,” said Ken. Frank continued to focus on “large” yacht projects through the 1950s. “These boats were around 80 feet which, for the time, was akin to building a 60-meter boat today,” said Ken. Frank also built smaller sport fishing boats in the 1960s. “Dad didn’t care what sort of boats he was building as long as the yard was busy.” While Frank built the boats, his wife Gertrude launched Yacht Interiors—one of the first interior design firms to focus exclusively on yachts.

Market change was coming, driven by a favorable economy and a material new to yacht construction. The Reynolds family of Reynolds Metals Company commissioned Burger to build a boat with a metal alloy that it supplied. The first all-welded aluminum yacht built in the U.S. was launched in 1955. Ultimately, this change in medium would prove to be a significant waypoint in custom yacht construction that neither Grebe nor Trumpy would successfully navigate. The first aluminum Broward, the 74-foot Howlen, was built in the Ft. Lauderdale yard in 1975. Broward’s shift to aluminum had been expedited by Frank’s purchase of the nearby Argosy yard, which had built a number of aluminum yachts designed by Jack Hargrave. Frank also hired two key former employees of Chris-Craft’s aluminum Roamer division. Don Nash had been foreman of the Roamer hull department and Donald Stroenjaus, the plant superintendent. “Dad and the ‘Dons’ designed Broward’s Saugatuck, Michigan, plant on airline napkins while traveling from Michigan to Florida,” said Ken.

“Broward North was built in Mom and Dad’s backyard.” The first boat was started while the well for the Travelift was still being dug. “Dad’s neighbors thought he was nuts. Even if he managed to launch the boats, how would get them past the low bridge at the Calumet locks?” Frank hinged the masts and flooded the bilges of the boats to gain a precious few feet. Over the next 20 years, 80 boats averaging 100 feet would be built in “Frank’s backyard.” The largest, a 120-footer, rose eight feet above the lock’s bridgework. “Dad sent her on her way in a snowstorm with a crew armed with welding machines and Sawzalls,” said Ken. The lock keeper watched in amazement as the crew cut away the top of the pilothouse, lifted it up and lowered it atop the deckhouse. Once past the bridge, the pilothouse was welded back in place.

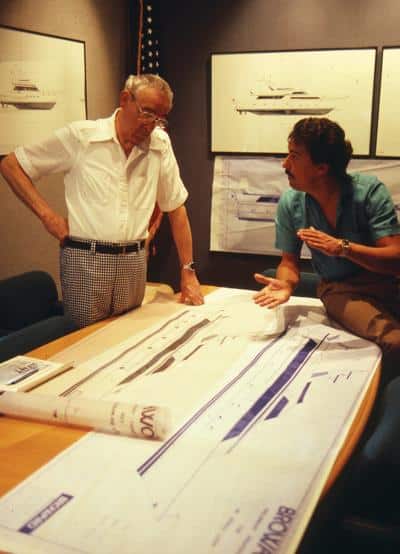

Ken’s older brother, Kit, ran the Ft. Lauderdale yard. “Kit did a great job, maybe too good a job,” suggests Ken. “Dad was one of a kind, but he was really a one-man show—Mom had held the family and the yard together.” After 12 years, differences with his father caused Kit to launch his own boat-building venture: Denison Marine. Ken was tapped to replace Kit and appointed vice president of new sales and construction in 1983. Ken had grown up in the yard and had worked in the lofting department, but he had not planned on running a boatyard. “Frankly, I was scared to death—it was a difficult situation,” admitted Ken. “Kit had a charismatic personality and the loyalty of the Ft. Lauderdale employees and customers.” Within six months, the bulk of the department heads, even the head of security, had left to join Kit at his new yard. “It didn’t seem to faze Dad—he told me to keep my head down and saw wood, ” said Ken. The advice paid off, and within six months Ken had sold two boats to customers in California. “I was lucky—they must have been the only two yachtsmen in the U.S. that didn’t know what had happened at Broward,” laughed Ken.

The market was heating up and Frank’s all-season (Florida) yard and his willingness to build on spec were paying off. “Dad would usually set up a new hull every 30 to 45 days,” said Ken. Broward North built a 95-footer in 30,000 hours while Broward South took 45,000 hours—it had the makings of a “civil war.” By this time, the Ft. Lauderdale yard was little more than a collection of leaky wooden sheds and an antiquated marine railway. Still, many felt the boats built in Ft. Lauderdale were superior in terms of outfitting and finish. Frank refused to waste time or money on what he considered unnecessary. Ken, on the other hand, recognized that a new, more demanding generation of yachtsmen was now driving the market. Frank dug in his heels while Ken attempted to upgrade the “Broward standard.”

Frank—or “Mr. D”—was a classic old school boatbuilder and not one to trifle with. He had thrown more than one know-it-all captain out of the yard, personally, and referred to engineers as “college boys” and yacht brokers as “buckets of steam.” “Dad could be charming when he wanted to sell a boat, but he was often blunt— signing deals was always a challenge,” said Ken. He remembers one meeting with a client and his lawyer as typical. Frank had been stewing quietly at the end of the conference table while the conversation about legal issues droned on. “Dad pushed his chair back, stood up and addressed our would-be client. This young fellow you brought along… your lawyer… he’s pretty smart, isn’t he? The client preened, figuring he had Dad on the ropes,” Ken explains. But Frank glared at him and snapped “if he’s so damn smart have him build your boat,” then left the room. “This was a big deal we had been working on for months…” Ken remembers. “We all sat there, dumbfounded.”

In addition to running interference, Ken invested in first-class advertising and owner rendezvous. “It had always bugged Dad that Henry Burger could check into Pier 66 during the season, walk the docks, and head north with a book full of orders,” said Ken. “Dad’s idea of marketing had always been to build the boats that Henry had no interest in…Henry had refused to build a three-stateroom 72-footer—Dad built a dozen of them.” Frank cringed at the thought of actually spending money on marketing. “On a bus packed with customers at the Nantucket rendezvous, Dad counted heads and said in a theater voice, Gertrude, why the hell is Ken throwing a party for people that have already bought a boat?”

Just as a perfect storm had filled Broward’s order book for a decade, another perfect storm would lead to the yard’s sale. Rejecting the calming hand of his wife and the youthful energy of his children, Frank built his last boat and sold the yard in 1999, having launched more than 220 Browards.

_

_

Fiberglass went on to compete with aluminum as the material of choice for series builders in the 80- to 125-foot market and aluminum and steel yachts would soar in size and numbers. And whether they welded aluminum, pushed pencils, or wrote the checks for the boats, many of the players that drove this boom in large yachts were graduates of “Broward-U.”