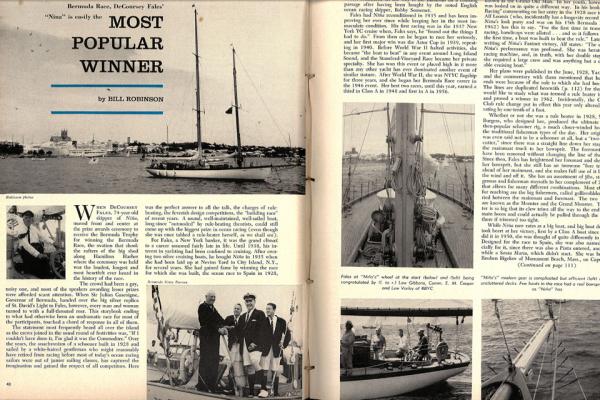

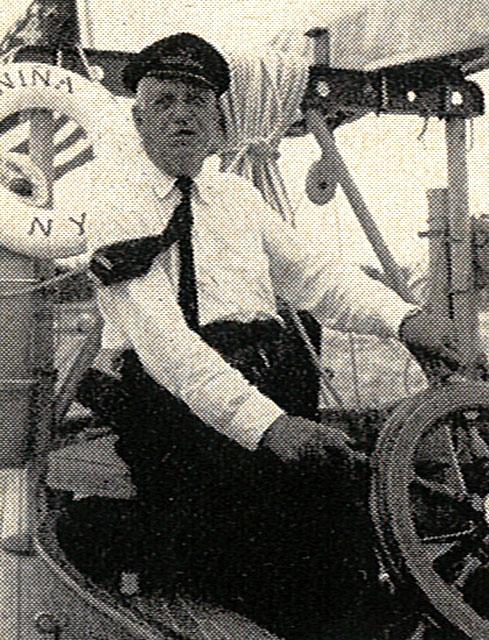

When DeCoursey Fales, 74 year-old skipper of Niña, moved front and center at the prize awards ceremony to receive the Bermuda Trophy for winning the Bermuda Race, the ovation that shook the rafters of the big shed along Hamilton Harbor where the ceremony was held was the loudest, longest and most heartfelt ever heard in the history of the race.

The crowd has been a gay noisy one, and most of the speakers awarding lesser prizes were afforded scant attention. When Sir Julian Gascoigne, Governor of Bermuda, handed over the big silver replica of St. David’s Light to Fales, however, every man and woman turned to with a full-throated roar. This storybook ending to what had otherwise been an undramatic race for most of the participants, touched a chord of response in all of them.

The statement most frequently heard all over the island as the crews joined in the usual round of festivities was, “If I couldn’t have done it, I’m glad it was the Commodore.” Over the years, the anachronism of a schooner built in 1928 and sailed by a white-haired gentleman who might reasonably have retired from racing before most of today’s ocean racing sailors were out of junior sailing classes, has captured the imagination and gained the respect of all competitors. Here was the perfect answer to all the talk, the charges of rule-beating, the feverish design competitions, the “building race” of recent years. A sound, well-maintained, well-sailed boat, long-since “outmoded” by rule beating theorists, could still come up with the biggest prize in ocean racing (even though she was once tabbed a rule-beater herself, as we shall see).

For Fales, a New York banker, it was the grand climax to a career assumed fairly late in life. Until 1938, his interest in yachting had been confined to cruising. After owning two other cruising boats, he bought Niña in 1935 when she had been laid up in Nevins Yard in City Island, N.Y., for several years. She had gained fame by winning the race for which she was built, the ocean race to Spain in 1928, under her original owner, Paul Hammond, as well as the Fastnet Race of that year in England. She also won the New London-Gibson Island Race in 1929. Then she lay idle for several years, and had one interlude in which she almost foundered on the way to the Bahamas on a cruising passage after having been bought by the noted English ocean racing skipper, Bobby Somerset.

Fales had Niña reconditioned in 1935 and has been improving her ever since while keeping her in the most immaculate condition. His first racing was in the in the 1937 New York YC cruise when, Fales says, he “found out the things I had to do.” From then on he began to race her seriously, and her first major win was the Astor Cup in 1939, repeating in 1940. Before World War II halted activities, she became “the boat to beat” in any event around Long Island Sound, and the Stamford-Vineyard Race became her private specialty. She has won this event or placed high in it more than any other yacht has ever dominated another event of similar stature. After World War II, she was NYYC flagship for three years, and she began her Bermuda Race career in the 1946 event. Her best two races, until this year, earned a third in Class A in 1948 and first in A in 1956.

At 34, Niña, was the third oldest boat in the 1962 race – Cotton Blossom IV and Chicane were build in 1926 – and she has rightfully earned the nickname of Grand Old Lady of ocean racing, just as her skipper, oldest in the race, is known as the Grand Old Man. In her youth, however, she was looked on in quite a different way. In his book “Ocean Racing” commenting on her entry in the 1928 race to Spain, Alf Loomis (who, incidentally has a longevity record to make Niña‘s look puny and was on his 15th Bermuda Race in 1962) has this to say. “For the first time in transatlantic racing, handicaps were allotted … and so it follows that for the first time, a boat was built to beat the rule.” Later on, in writing of Niña‘s Fastnet victory, Alf states, “The effect of Niña‘s performance was profound. She was berated as a racing machine, and, in truth, with her double staysail rig she required a large crew and was anything but a comfortable cruising boat.

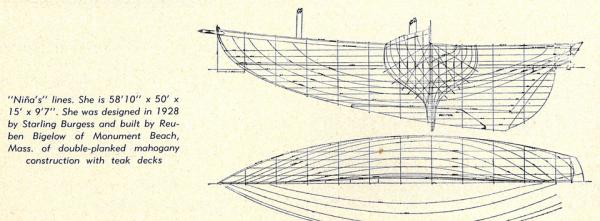

Her plans were published in a the June, 1928, Yachting , and the commentary with them mentioned that her short ends were because of the rule to which she had been built. The lines are duplicated herewith (p. 112) for those who would like to study what was termed a rule beater in 1928 and proved a winner in 1962. Incidentally, the Cruising Club rule change put in effect this year only altered Niña‘s rating by one-tenth of a foot.

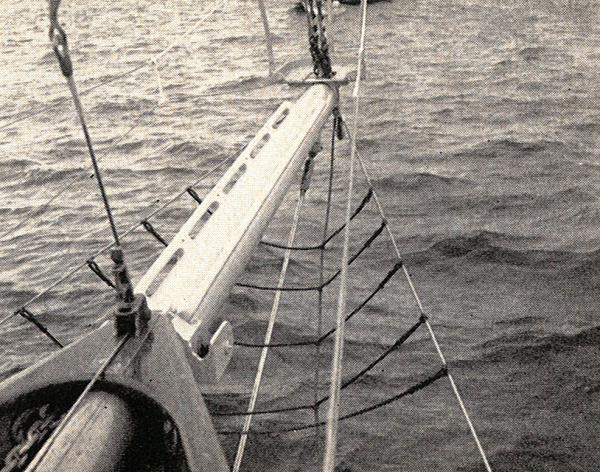

Whether or not she was a rule beater in 1928, Starling Burgess, who designed her, produced the ultimate in the then-popular schooner rig, a much closer-winded boat than the traditional fisherman types of the day. Her original rig was even said to not to be a schooner at all, but a “two-masted cutter,” since there was a straight line down her stays from the mainmast truck to her bowsprit. The foremast could have been removed without changing the line of the stays. Since then, Fales has heightened her foremast and shortened her bowsprit, but she still has an immense “fore triangle” ahead of her mainmast, and she makes full use of it both on the wind and off it. She has an assortment of jibs, staysails, genoas and fisherman staysails in her complement of 23 sails that allows for many different combinations. Most effective for reaching are the big fisherman, called golliwobblers, carried between the mainmast and foremast. The two biggest are known as the Monster and the Grand Monster. The latter is so big that its clew trims all the way to the end of the main boom and could actually be pulled through the sheave there if trimmed too tight.

While Niña now rates as a big boat, and big boat devotees took heart at her victory, first by a Class A boat since Argyll did it in 1950, she was thought of quite differently in 1928. Designed for the race to Spain, she was also named especially for it, since there was also a Pinta entered, and for a while a Santa Maria, which didn’t start. She was built by Reuben Bigelow of Monument Beach, Mass., on Cape Cod, a craftsman who had never built anything bigger than a catboat before. Her construction is double planked, mahogany, with teak decks.

There was a great fuss over “small” boats going in a Transatlantic race for the first time, and the account by Weston Martyr in the Sept. 1928, Yachting of her arrival off Santander made much of the drama of such a little boat being first to finish. The small boats had started a week ahead of the 180-200 footers, such as Atlantic and Elena, in the big class. When Niña was finally identified Martyr’s account says “…we look at each other dazed. For instead of the great, redoubtable Atlantic that we had come out to greet, it is the Niña, the little Niña – the smallest boat in the fleet.”

Another finish spectator was excited too. He leaped to the cabin top of the launch he was riding, waved his cap and shouted, “Well sailed, Niña! I congratulate you. I am the King of Spain.”

And so Niña has had a long career of causing furores and gaining respect. From a “rule beater” and a “small boat,” she has evolved into the champion of the traditionalists and the savior of the big boats. The excitement surrounding her entry into Hamilton Harbor was equally as high-pitched as her arrival off Santander 34 years ago, even without royalty to greet her. Officials of the Royal Bermuda YC hastened out to welcome her as she powered through Two Rock Passage into the anchorage. At the same time she was only a strong possibility as a winner and smaller boats had a chance to catch her, but there was a growing feeling that she had done it, and the crowd watching the results being posted on the RBYC bulletin boards cheered every time a new batch of finishers failed to dislodge the old girl.

Finally, shortly after midnight, early Thursday morning, when Lancetilla II, the top time allowance boat, had failed to finish, within her time, the popular result became official.

As far as the racing went, there was nothing dramatic or unusual about Niña‘s performance. She had “schooner breezes” for perhaps 75 per cent of the time, with a golliwobbler up. She was never within a plank of putting her rail under, carrying full sail, and she made runs of 200 and 214 miles in the first two days. Perhaps the key to her victory came Sunday night when she had several Class A boats in sight ahead. Instead of holding high of the rhumb line to make more westing while crossing the Gulf Stream, Fales decided to slack sheets a bit and drive her off, paralleling the line.

By this decision she got a bit to the east of many of her rivals and suffered less from the great calm that caused so many boats to go dead after two days of glorious sailing. Niña had it for about 12 hours, starting Monday evening, but she was dinghy-raced through it, with every zephyr played for what it was worth and constant sail changes to catch what catspaws there were. Drifters, gollies, spinnakers, genoas and other light sails in varying combinations were worked carefully and she never lost way, gradually moving into better air by Tuesday morning, while the bulk of the fleet had to wait until much later Tuesday for it. She saw no other boats after dropping Petrel astern on Monday afternoon until she sighted Stormvogel on approaching North Rock.

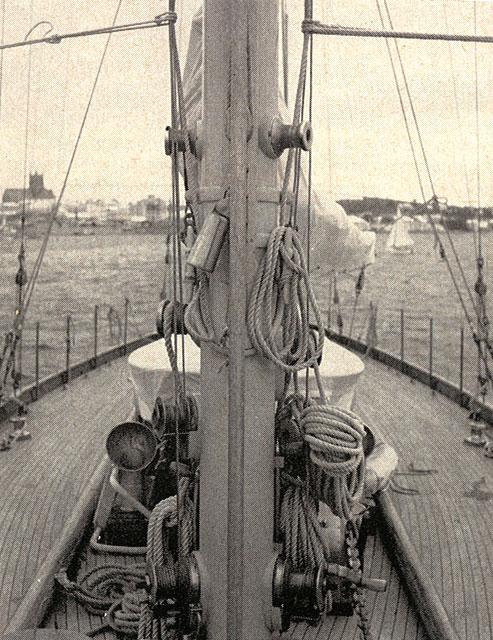

Niña‘s gear is as modern as the newest racing machine. Despite the complexity of lines needed to handle a schooner rig, she has remarkably uncluttered decks, and her winches and fittings are right up to date. There is a clean efficiency about every inch of her, and her hollow mainmast, built with the boat, looks as new as it did in 1928.

Fales, who stands watches and handles the wheel often, has naturally been able to collect a topnotch crew to sail with him, and he gives full credit to them whenever he is congratulated. The watch captains were Peter Comstock and Capt. Arthur Schuman, USN, and Dan Bickford was the navigator. Also in the crew were: Howard L. Payne, John Sinclair, Harold Wilder, William Close, Tony Hogan, Radley H. Daly, Charles L. Stone, Dr. Paul Sheldon and Capt. Trygve Thorsen.

Grand old girl that she is, and as wonderful a chapter in her career as this popular victory was, everyone who races knows that Niña has many more winning races ahead of her.