Bolero

The legendary yacht Bolero was built for yachtsman John Nicholas Brown by Henry B. Nevins at his yard in City Island, New York, and designed by Olin Stephens of Sparkman & Stephens. As a client, Brown was a stickler for detail, and one can imagine the discussions around the drafting table. By the time the black yawl was ready for launching in 1949, seven pages of calculations had gone into determining the right propeller, six sets of plans had been reviewed, three dozen minutely detailed scale drawings had been created, 37,000 man-hours had been billed and more than 100,000 bronze wood screws had been used in her construction.

She was a thing of beauty; it wasn’t long before Brown and his wife were known as “Bolero’s Browns.” Bolero came on the yachting scene during those early postwar years, and she seemed to represent hope for a better future — the nation was captivated by her luxury. Bolero was also fast. Seventy-two feet long on deck, she was near the maximum under Newport-Bermuda Race rules, and Brown was keen on racing his yawl. Bolero crossed the finish line first in the Newport-Bermuda Race in 1950, 1954 and 1956, at that time setting a course record that lasted 18 years.

In a surveyor’s report requested by married couple Ed Kane and Marty Wallace, the latest owners of Bolero, the surveyor emphasized the historical significance of the yacht, stating “the custodial obligations and responsibility to history.” But the new owners were well aware of her pedigree, noting that in this single boat were the legacies of a great designer, great builder, great owner and great racing record. Stephens himself once confided to Wallace that these boats were never designed to last this long. The assumption was they would be sailed for 15 or 20 years and then be gone. He was amazed that he had created something for the ages.

When Bolero came along, Kane and Wallace had already been involved in the restoration of Marilee, a 1926 NY40, and their own cruising boat was a Bristol 47. They didn’t really need another project. But as a New York Yacht Club member, Kane had enjoyed drinks at the Bolero Grill and had admired the Bolero model at the club. He was smitten, and Bolero became Kane’s personal rescue mission. Advised it would be in his best interest to get Bolero out of the yard as soon as possible, with the aid of some hardy friends Kane and Wallace sailed her up Chesapeake Bay to Oxford Boatyard in Maryland — the first step in Bolero’s long road to recovery.

Kane and Wallace then had some preliminary refit work done at Pilots Point in Connecticut — planking under the waterline, a new stem, a new step for the mizzenmast, systems work, new tanks and batteries. Though they were aware there could be problems with the deck, which was teak over cedar, they opted to get in some racing before tackling what could be a bigger restoration project. For three years they raced Bolero pretty hard in Europe, and the plan was to get in one more year of racing before enjoying a leisurely transatlantic sail back to the States. But a phone call from the crew at the boatyard where Bolero was stored in England brought an end to those plans: They had found cracked frames. More calls, more broken frames … Wallace says, “We were like, that doesn’t sound very good,” and that turned out to be an understatement.

When the boat arrived at Rockport Marine in Maine, it was discovered that out of 120 frames, 47 hull frames were not just broken; they were snapped in two and pulled away. The teak overlay on the cedar deck carried out to the edge of the covering board, but the seal was not tight. Water had worked its way down through the seam and around the boat, basically keeping the joint between the hull planking and the frame constantly wet.

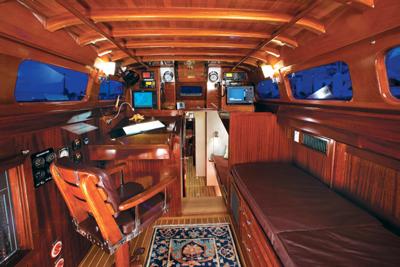

Belowdecks, above the headliner, there was quarter-inch plywood in place to cover up the unsightly deck leak. Once yard workers ripped that away, they discovered that the deck beams had pockets of rot because of the lack of ventilation. Ultimately, they decided to rip out the entire interior and do the framework from the inside. Yard owner Taylor Allen electronically measured the boat and, fortunately, found that at 73½ feet long she was still very close to her original design shape, attributed in large part to monel web frames inside the boat. Yard manager John England was impressed: “Those things had not moved one iota in 60 years.”

Not many yacht owners would have the fortitude necessary to endure a 95-percent, 22-month refit. Wallace admits, “We swallowed hard but we couldn’t pull the plug on Bolero. She is an iconic part of the yachting scene, and it was a do-or-die situation.”

They have now owned Bolero for more than 10 years — longer than the Browns — and there are many memories. Kane remembers an occasion when Olin Stephens came to the yard. He was then 95, and while Kane was trying to figure out a way to get Stephens aboard, even contemplating the use of a forklift, he turned around and discovered Stephens had climbed the 12-foot ladder and was already busy surveying the deck work.

“One of the things that had always bothered Olin was the varnished wood on the stern,” Kane says. “It was originally black, and now, once again, it is painted black like the rest of Bolero. Olin always use to say, ‘My God, it looks like somebody chopped off the stern with a chain saw.’ I wish he had lived long enough to see that it’s gone back to the original.”

Feeling nostalgic? Take a trip down memory lane with this gallery of vintage Yachting covers.