120210cnst-7028.jpg

While walking through one of Hodgdon Yachts’ manufacturing facilities, I picked up what I thought was a solid wooden locker door that measured about two feet by three feet. I say thought because it looked like wood, it felt like wood — heck, it even smelled like wood. But it weighed about as much as a Frisbee. The door had been hollowed out and the core replaced with lightweight honeycomb aluminum. While this is hardly a simple process, it’s just a small example of the capabilities that Hodgdon Yachts has been developing.

“We’re not just a little old boatbuilder in Boothbay,” said Ed Roberts, Hodgdon’s director of sales and marketing. “A lot of people don’t know we’re America’s oldest boat company, and a lot of people don’t know we’re working in advanced composites.” The yard opened in 1816.

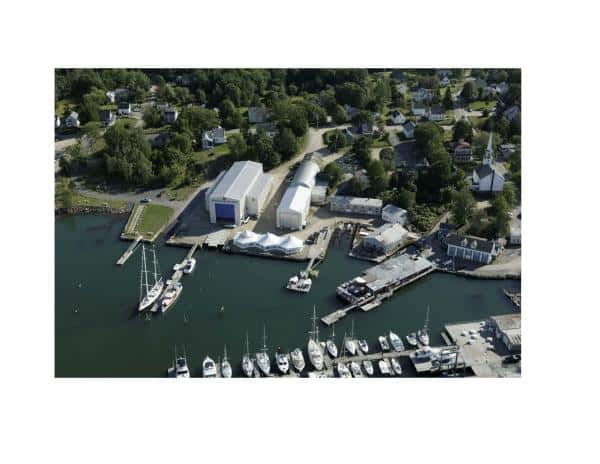

Hodgdon Yachts is actually made up of five divisions, with headquarters in East Boothbay, Maine. Originally known for building plank-on-frame and cold-molded sailboats, the company has expanded its capabilities to a wide variety of advanced composites in the construction of hulls and decks, as well as interiors (View our complete photo gallery here).

The irony for Hodgdon is that its almost under-the-radar existence has attracted famous clients who covet their privacy, but this is one of the company’s biggest hurdles. Pages-long confidentiality agreements accompany so many of the boats that come out of the facility that the company has not been able to benefit from the exposure that these specialized vessels would normally generate. “We’re the best-kept secret in the boating industry,” Roberts said with a laugh.

At its headquarters, Hodgdon has three building halls with more than 55,000 square feet of space divided among construction, finishing and offices. From the outside, the offices look like those you’d find at a typical small company, but in the reception area, photos of some of the company’s more famous sailboats, such as Antonisa, Scheherazade, Windcrest and the commuter Liberty, as well as signed photos from naval departments around the world and proclamations from the U.S. Department of Defense tell another story.

Hodgdon has worked closely with the University of Maine researching various composites, as well as timber, for use in boat construction. Under contract to the Office of Naval Research, Hodgdon Defense Composites developed the 83-foot Mk V.1 High-Speed Composite Craft. Nicknamed Mako, the boat was constructed with a carbon fiber/Kevlar composite and powered by twin 2,400-horsepower MTU diesels turning Kamewa waterjets. Top speed is 50-plus knots; the range is 500 nautical miles. The boat was developed to showcase the ability of high-performance composites to absorb the shock of wave impacts. Launched in January 2008, Mako met or exceeded the basic requirements for operating speed, weight, capacity and range. The composites used to build the boat were engineered from a proprietary formula developed for the Navy by Hodgdon’s engineers.

All the experience gained from working on Mako and other naval vessels was applied to the most recent big project — an ultrahigh-performance triple-engine motoryacht that no one can talk about in significant detail. Roberts said that, at one point, Hodgdon had 12 full-time engineers working on that one boat. Many in the marine industry wouldn’t have believed that Hogdgon had half that number of engineers on staff. Highlights of the new boat include a computer-controlled anchor and rode. The hatch on the locker pops open, the anchor deploys, and the computer counts the chain links as the anchor is lowered. In addition to controlling everything on the bridge, the command system monitors every function on board, right down to alerting the captain that a bulb in the forward stateroom is ready to burn out.

Continuing our tour, a car ride about 20 minutes to the west brought us to the Hodgdon Yachts Interiors division in Richmond, Maine. In addition to developing the living spaces for its own boats, Hodgdon regularly produces them for other custom yachts, combining classic, glowing wood with weight-saving technologies. The company has the ability to manufacture complete interiors for boats of up to approximately 260 feet. In one corner of the facility was a jig for a circular staircase for a 154-foot yacht, while in another location I spied a 22-foot cabinet that must be taken apart to fit into its new home.

“We understand the custom business quite well, and we have a very strong engineering capability. Because we are a builder, we are very good at the integration from plan to build,” Roberts explained. Hodgdon’s designers and engineers can take renderings from outside sources and develop an interior or start with a blank sheet of paper. The process begins with a full-scale mock-up of a sample cabin on a given boat. Once the owner or captain approves, the assembly of the interior begins.

When the furniture will be installed at a location away from Hodgdon, it’s especially important that the final product fit as seamlessly as possible. This is where the company’s 3-D computer modeling comes into play. Every piece of furniture or cabinetry on a given boat is first designed on a computer so that it accurately fits into the space on board. Some final smoothing out always needs to be done when the pieces go into the boat, but the three-dimensional modeling and extra steps of rough-in work that take place ensure that the interior goes into its new hull as easily as possible.

“There aren’t many shops who can do this kind of work,” Roberts said. A sample countertop started life as a piece of solid wood, but in the center of the panel, the interior core was removed and replaced with lightweight foam. The panel was still solid enough at the rim to support a sink, but the weight savings were there. Roberts estimated that building an interior with composite-cored panels can save up to 60 percent in weight.

To arrive at the same real-wood appearance, Hodgdon can also fabricate panels from honeycomb-cored veneers that are finished in a nine-step process of pickling and staining. The final version can be anything from sycamore to cherry, and there’s no way the naked eye can see the difference.

Hodgdon’s craftsmen use a coping splice where joints overlap to create a stronger joint. On veneers, the woodworkers use panels twice as thick as a lot of other builders because they know that owners will eventually want the pieces refinished. The additional thickness permits sanding and reworking in the future. The same thinking applies to louvered vents and doors. The louvers are cut out on a numerically computer-controlled router, and on the back side, the louver strips are designed to be removable so that if you damage a slat, you can easily replace it.

In spite of this high-tech construction, an interior still needs to come apart so crew can have access to the systems. Hodgdon didn’t want to use wood screws to fasten removable access panels in the interior because these bore out and loosen over time. To solve the problem, the engineers developed threaded inserts so the fastening hardware would stay tight over time.

As we entered the Hodgdon Yachts headquarters and passed by the pictures and proclamations in the reception area, Roberts remarked that, despite the secretive nature of their many projects, he’s hopeful that people will realize the capabilities that exist at the company. “It’s heartbreaking to see these guys go to Europe when we can build equal or better quality here,” he said.

Hodgdon Yachts, 207-633-4194; www.hodgdonyachts.com