29minutes445.jpg

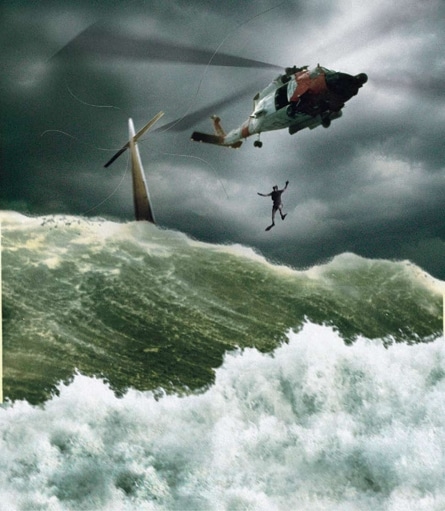

Rescue swimmer David Yoder sat quietly in the rear of the Coast Guard HH-60J helicopter while it flew toward his first rescue. “The most difficult part for me was thinking about if we’d have to ditch the helicopter or not,” recalled Yoder. “On our way out the C-130 pilot recommended we not do the rescue because the seas were so rough out there.” Yoder was thirty-two years old, qualified during the past summer as a rescue swimmer. Heading out, he didn’t question himself or his inexperience. He was focused on his job, rescuing survivors.

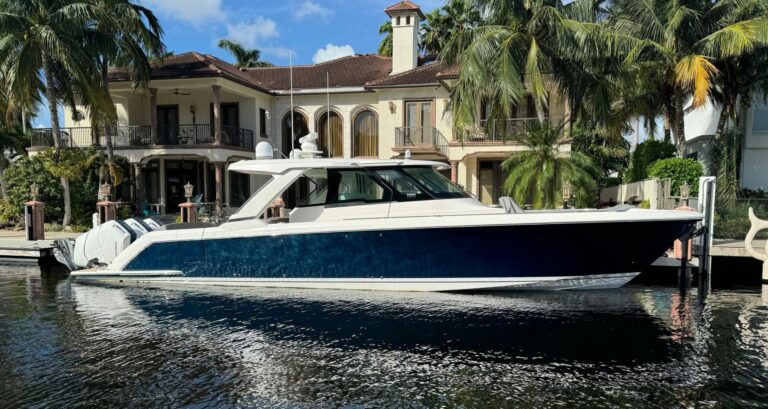

The forty-one-foot Malachite had capsized twice-each time, it righted itself from three-hundred-sixty-degree rolls. On one occasion, the forty-one-year-old Canadian captain and owner, Nicholas Hull, while strapped to the helm, was taken completely under the water. Hull’s left side had also been slammed by the boom, which crushed a rib on impact. Mark Termint, a forty-one-year-old crewman, suffered from a lacerated finger. Ron Reggev, the eldest on board at sixty-one, had multiple bruises on his back from the boat being hurled up and tossed down the crests of monstrous waves.

When the New York-based U.S. Coast Guard Atlantic Area RCC was notified that Malachite was in very heavy weather and breaking up, officials quickly plotted the coordinates, nearly 275 miles west of Bermuda.

At 1:55 p.m., after an hour of searching on scene, a C-130 aircrew located Malachite. The vessel at first appeared to be just another whitecap. Then they observed the ketch confronting enormous seas. When a swell approached, the vessel rode up the wave crest about halfway. The wave’s height extended another forty feet or so above the top of the vessel’s fifty-five-foot mast.

For the greater part of the early afternoon, Lt. Bruce C. Jones and Lt. j.g. Randall Watson, the pilots of the duty helicopter, consulted with the operations center and aircrew members, flight mechanic Dave Barber, and rescue swimmer Yoder. In preparation for the mission, they took the unusual step of mounting on the Jayhawk’s undercarriage three external fuel tanks, which looked like missiles, in addition to a starboardside one-hundred-twenty-gallon fuel tank. With the extra fuel and blessed with a favorable tailwind, they calculated they would be able to make the 632-mile transit to Bermuda. This journey would include a half-hour on scene for the rescue before continuing on to Bermuda with a forty-five-minute fuel reserve.

The commanding officer of Air Station Elizabeth City, Captain Norman Scurria, concerned about the mission demands, questioned each member of the rescue team. “This was the first time I had a CO come in on the weekend to pull each of us aside and say, ‘If you do not want to go, you do not have to,'” recalled Barber.

At 6:20 p.m. the Jayhawk arrived on scene. “We found the boat pretty quick,” said Yoder. “Up until now, I’d been sitting in the back of the cabin. When I looked out the door to see the boat, it was an amazing sight . . . the waves were at least eighty feet high and that boat was being tossed around and over the tops of them.”

Jones carefully positioned the helicopter in a hover and about one hundred yards off Malachite’s starboard side. The aircraft’s floodlights and a directional spotlight illuminated the condition of the vessel. Malachite’s sail was torn into ribbons, and six of the stays that held the mast upright were broken and swinging outward or trailing behind in the surf. Even though the crew had deployed a sea anchor, Malachite was forced along at eleven knots.

As the flight mechanic, Barber needed to devise a plan to safely hoist the men without putting the helicopter in danger. “The seas caught me off guard,” said Barber. “On the stern of the vessel, where a rescue basket delivery could have been made, a boom was swinging wildly from port to starboard.” Barber brought this to Jones’s attention. “From that point, the pilot and I knew that a trail line hoist to the boat was out of the question.” Barber suggested another option, something he had done before during Hurricane Charlie in 1986. The three men on Malachite could secure themselves together and go overboard as a group. Then the rescue swimmer would attempt to help each of the men into the rescue basket, which Barber would hoist to the safety of the cabin.

After discussing the procedures with his crew, who all agreed that it was highly unlikely Malachite would stay afloat much longer, Jones contacted Malachite’s Captain Hull, on the marine radio. Jones said, “Well, fellas, here’s your choice, you could wait for another resource to get here, or jump into the water, but I can’t hoist you directly from the boat.” According to Jones’s report summary, “the captain immediately replied that he and his crew wanted off.”

“I can’t say that I wasn’t surprised,” Jones reflected. “You’re out there almost four hundred miles in the ocean and the seas are bad and you’re thinking to yourself, Good God, they must really want to get off that boat.”

Watson recalculated the wind speed and direction, the distance to Bermuda, and the amount of fuel remaining. They had precisely thirty minutes on scene before they needed to depart for Bermuda. Jones said, “I asked Dave Yoder to confirm he was ready and wanted to deploy. He was like, ‘Oh yeah, send me in, Coach.'”

“When I placed the rescue swimmer in the water he was only five feet from the three survivors,” Barber wrote. It was a struggle for Yoder to swim toward the men-he was repeatedly forced under the surface by the rush of huge seas collapsing over his head. The pilots also had challenges just keeping the aircraft airborne. With no visible horizon, Jones used the night flares previously dropped by the C-130 to assist him as a visual reference. Soon the flares were swept away. Describing the situation, Jones said, “It’s dark, dark sky, dark water. You can see what’s in the illumination of the searchlight-that’s really all you can see. You can’t tell which way is up-are you leaning to the left? Are you leaning to the right? Are you going backward or forwards? It’s a constant struggle to focus on what’s in the searchlight. Then repeatedly flicking your eyes to the left to see your gauges to see if you’re climbing or descending. You’re trying to hold a steady altitude, but the seas below you are moving up and down twenty-five to thirty feet at a time you get a sensation that you’re falling it’s very disorienting.”

In order to see Yoder and steady the hoist cable with one hand to maintain a basket position near the swimmer, Barber kneeled and leaned way out of the cabin door, strapped to the deck by a safety harness around his waist. Because of the twenty-five-foot rise and drop of the seas from under the basket, Barber constantly hoisted the cable up or down with his other hand. Additionally, he had to provide visual and directional information for the pilots. He became their eyes and ears during the rescue because the pilots could not see what was happening behind and below them.

Watson continued to monitor fuel gauges while communicating with the C-130, which circled overhead. Despite the decreasing time and fuel reserves, he calmly called out approaching swells to Jones and provided updates about how much time they had left on scene.

Yoder finally reached the men with great effort. He directed one man to unhook and swam with that first survivor, Mark Termint, toward the rescue basket by holding onto his life jacket. “My hands would get within four inches of it and the problem is, I could see the basket under the water, then all of a sudden it would disappear,” described Yoder. The basket would slingshot away from him.

“The swells would drop twenty, forty, sixty feet,” Yoder realized. “By the time I got to the basket, the swell was going up and the hoist cable would have twenty feet of slack-which would go through the bail on the basket and then pull tight when the swell would go down again.” During one of these cycles, Yoder managed to get Termint into the basket, rear end first, just before the cable pulled tight and “snatched him up and he was gone.”

“Fifteen minutes,” Watson forced himself to calmly report.

Jones noticed after this first rescue that Yoder was tired. “I was having second thoughts about this mission. I looked at the clock, looked at our fuel, and thought, If they all take fifteen minutes, we’re never going to make it. Did I do the right thing putting Yoder down there?” Jones knew there was a very real chance someone might be left behind as the helicopter was forced to leave and refuel.

Barber located Yoder, identifying him by a green chemical light attached to his snorkel mask and another in his gloved hand. He flashed the spotlight on the remaining two men and then on to Yoder to show him where they were-about seventy-five yards away.

Yoder and Barber went through another ordeal trying to get Reggev into the basket. One swell was close to one hundred feet. Barber started to hoist Reggev up. Yoder recalled, “As the basket came up, the swell came up, and it put me so close to the helicopter I could feel the heat and probably could have grabbed on to the tire and climbed into the helicopter. All I could think about was that the rotor blades were going to hit the water!”

The hoists were a violent and physical battle for everyone on the Coast Guard team. Yoder was smashed against the rescue basket repeatedly before it dropped a couple of car lengths beneath him into the ocean. Barber tried to maintain cable control. “I had the cable snatched out of my hands twice, violently straight out.”

“Ten minutes,” Watson uttered, a forced-calm announcement.

About fifty feet from Yoder, Captain Hull swam to meet him. Yoder helped him into the basket with all his strength. He was a tall, heavy man, over six feet. According to Barber, the captain must have weighed 275 pounds dry. “Just as I was bringing him up out of the water, a large wave crashed on top of him. I thought he was going to be dumped back out of the basket,” Barber wrote.

“Five minutes remaining,” Watson said, forcing his voice to sound unruffled.

Yoder watched the captain enter the cabin of the helicopter above. Barber gave Jones conning instructions to position the helicopter as he lowered the hook to the ocean’s surface where Yoder could see it. Then he paid out additional slack to compensate for the rise and fall of the seas. This sank the hook about five feet. Barber started to take back the slack slowly as Yoder approached.

Suddenly he felt a broken strand of cable, or “spur,” hit his gloved hand. He quickly stopped the hoist to prevent his caught hand from going into the drum. “I watched the strands break right in front of my face . . . One, two . . . as the third was about to break, it was like ‘Oh my God this can’t be happening!’ It unraveled in front of my eyes!” Barber recalled.

He made a split-second decision, hoping to save Yoder’s life. It was one that they would not even try in a training scenario because the hoist would become unusable after the fact. “I was betting on all of the remaining cable going into the drum, I had three-fourths of it to go, and I didn’t think it would snag.” With no time to inform the pilots, Barber took what he had, three to four seconds, to instinctively two-block the cable, feeding it into the drum at full speed. With great difficulty, Barber managed to pull Yoder, who had no idea what had just happened, up to the doorway of the cabin.

“I had every confidence in Dave Barber because he trained me,” said Yoder. “But, I have never been so happy as when I saw the door of that helicopter.”

The helicopter with the three survivors landed at Naval Air Station Bermuda about an hour and a half later, signifying the end of what was recorded then as the longest operation for a HH-60J Jayhawk helicopter crew. The mission totaled 5.1 hours.

“They gave me thirty minutes to do the job,” said Yoder, proudly. “I did it in twenty-nine.”

From the book So Others May Live by Martha LaGuardia-Kotite. Copyright © 2006 by Martha LaGuardia-Kotite. Used by permission of The Lyons Press, www.lyonspress.com