Offshore Safety Lessons

The sound of cracking thunder, howling wind, and breaking seas was deafening. For visual effect, nature’s light show acted like flickering ballpark floodlights on the 40-foot seas, giving intermittent glimpses of how bad the situation was. I was sitting alone in the dark cockpit of a disabled 40-foot sloop, 400 miles off Cape Hatteras, sipping the last of the rum and trying to spot the ship that had responded to our Mayday.

Finally at 0430 I saw the immense, dark hull of the 1,100-foot tanker, Venture Independence, as it rose on the swells and then disappeared into the troughs. Radio contact established that a rescue attempt would be made at daybreak; giving me an hour and a half with nothing more to do than figure out how in the world I got myself into this mess.

It happened 23 years ago when I eagerly agreed to crew aboard a client’s Intrepid 40 he was sailing from Annapolis to Bermuda with his childhood buddies. She was stoutly built by Cape Dory and superbly designed by Chuck Paine, and the owner seemingly had spared no expense in maintaining and outfitting her, although I later discovered a few items crucial to a safe passage had been overlooked or ignored.

Up to this point, my offshore sailing experience had been limited to overnight passages up and down the East Coast, usually within 20 miles of land. Based on my monthly digestion of nautical magazines, though, I knew enough to ask a few safety-related questions, such as whether the boat had storm sails and a sea anchor. “Don’t worry. Our sails are in good shape, and we can always trail our dock lines if necessary,” was the owner’s answer. Since GPS technology had not yet reached the recreational boating market (making this voyage seem ancient), and LORAN was not effective far offshore, I also asked who would be serving as navigator. “Don’t worry, one of the crew is an experienced navigator and electronics whiz.” And lastly, I wondered how much sailing experience the additional three crewmembers had. “Don’t worry. They’ve been sailing since they were kids.” Geez, I guess I should learn to stop worrying.

Little things can be a premonition of big things to follow, and I began worrying again when I got on board and saw the “electronics whiz” feverishly splicing a maze of wires behind the electronics panel at the nav station. He had begun to install a new Single Side Band (SSB) radio and weatherfax just hours before departure. Having built my own ham radio gear as a kid, I knew that installing a SSB was not exactly a “cut ’n splice” operation.

Soon, more signs followed. As we began our trip south on the Chesapeake Bay our “navigator-electronics whiz,” taking a break from his DIY electronics project, poked his head out of the companionway and asked what the big object was to starboard. It was the wellknown, often-photographed Thomas Point Lighthouse, 15 miles from where this fellow lived on his boat. Uh oh.

We arrived in Norfolk, Virginia, the next morning, having motored all night into headwinds, and thus preventing me from observing these “lifelong sailors” in action. After stopping briefly for our navigator to “call” NOAA and get the latest weather forecast (believe it or not, there was a time before cell phones and WiFi) we headed out to sea, hopefully in the direction of Bermuda. According to our navigator, NOAA was reporting a gale off Hatteras, but according to his calculations it was moving north quickly and would be past us by the time we reached the Gulf Stream. Just before I shut down the Perkins diesel, I noticed another little thing that should have been a premonition of things to come—the engine’s temperature was higher than normal. But why worry? We were finally underway.

Sailing that day was invigorating, but as the seas and wind began to build, most of the crew, including the owner, became seasick. To make matters worse, I soon learned that my shipmates’ experience of “sailing since childhood” consisted of a few days at summer camp on a Sunfish. “Halyards,” “sheets,” and “coming about” were new terms to this crew. This was going to be a long voyage.

Later that evening I noticed our running lights getting dimmer and discovered our house batteries were down to just 10 volts. After running the engine for about 30 minutes to charge the batteries, it overheated and had to be shut down. All nonessential electrical equipment was turned off, and with three of the crew now severely seasick and unable to function, we decided to wait until morning to troubleshoot the problems. But the sea wasn’t done with us quite yet, and in the middle of the night we were startled by the sudden, snapping sound of a parting halyard and the falling of our headsail into the sea. After an hour of hauling and securing it to our lifelines we proceeded to sail under main alone, waiting until daylight to make repairs. I was beginning to have a sinking feeling about this voyage.

At daybreak we raised our headsail using a secondary halyard, and with three of the crew still sick, I proceeded to troubleshoot the engine problem. It was difficult working in the confined area as seas were now running 8 to 10 feet, but I finally found the cause of overheating. With all its teeth missing, the engine’s impeller was totally shot. While I was able to replace it, I couldn’t find all the missing parts within the cooling system. An after-market refrigerator enclosure had recently been installed in a location that prevented me from reaching all of the engine’s hoses. Running the engine again confirmed that the cooling system was clogged, and major repairs would have to wait until we reached port.

Next on my list was the electrical problem. While our “electronics whiz” was lying face down on the cabin sole, I opened the back of the nav panel and discovered the SSB and weatherfax had been hard-wired to the house battery bank without fuses. The motion of our vessel had apparently caused an intermittent short circuit, which was discharging our batteries. I disconnected the spaghetti, making sure the engine battery was isolated from the house circuits.

When the owner woke that morning, we all spoke about our situation, and it was decided we would continue to Bermuda. As long as we could sail and had enough battery power for our VHF and LORAN, which supposedly would function as we neared Bermuda, we would be fine. Little did we know what kind of weather was ahead.

Approaching the Gulf Stream, the wind increased to a steady 30 knots, clocking around to the northwest and causing the seas to build to 20 feet. With a reefed main and a furled headsail, the boat was handling the conditions far better than the sick crew, two of whom hadn’t yet set foot on deck since we left Norfolk. One insisted on staying in the forward stateroom, the most uncomfortable spot on the vessel. The other, our “navigator,” told me he was suffering from vertigo and was afraid to step out into the cockpit. That left the sick, but valiant, owner, his childhood buddy with no sailing experience, and me, who admittedly was in over my head, to get us to Bermuda.

As nightfall arrived the conditions worsened. The winds were now blowing a steady 40 knots, and I could only estimate the seas to be 25 to 30 feet, with some breaking on us. I decided to wake the owner and have him take the helm while I tried to get some rest. His relatively healthy buddy kept him company in the cockpit while I went below and jammed myself into an aft cabin berth. Two hours into my sweet dreams I woke suddenly to the horrible sound of rushing water and crashing objects. My body was being pushed against the lockers above my berth. We had taken a knockdown, and stuff was flying everywhere. With the owner yelling from the cockpit, “We’re okay! We’re okay!” I quickly put on my survival suit and looked around the main cabin with a flashlight. It was total chaos. Our navigator had been thrown across the cabin and was injured. The crewmember in the forward cabin seemed totally out of it and unaware of where he was. (I later suspected he had been taking tranquilizers.)

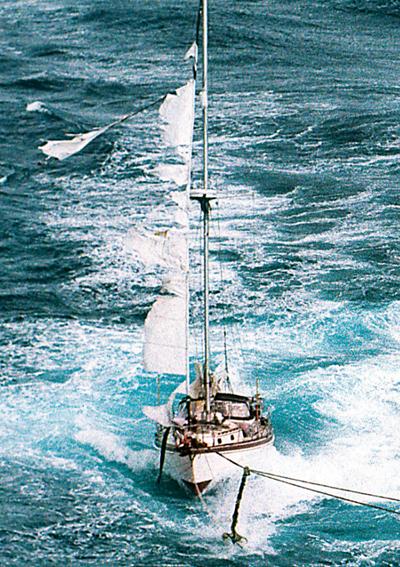

The scene outside was mayhem. The seas were monstrous and breaking all around us. I heard a sickening sound forward the moment I set foot in the cockpit. Our headsail, now furled into a tiny sliver of a sail, exploded into ribbons. We had taken the main down completely, so we were now running under a bare pole without much steerage. Thinking we would have better control with a triple-reefed main, I struggled for an hour to get it set. But as soon as we fell off, it exploded into shreds as we took another knockdown. Bad decision. The wind was now blowing 60 knots and gusting even more. We felt beaten, exhausted, and partly in shock. Three crewmembers were still sick, and one had badly bruised ribs. We had no sails. Only one battery had any juice left, and the engine couldn’t be run for more than a few minutes before overheating. There were few options left except to send out a Mayday.

Miraculously at 0330 we heard a response through the radio static and noise outside. The supertanker, Venture Independence, was within 10 miles of us and could see us on its radar. It arrived within the hour, and the captain suggested we wait until daylight before attempting to transfer to his ship. According to the ship’s radio operator, the winds were now blowing 65 knots and the seas were averaging 43 feet.

At daylight, with Venture Independence to windward, we started up the Perkins one final time and brought our vessel alongside. The ship was returning to Gibraltar with empty tanks, so its freeboard was 100 feet or more. Although the conditions had improved, the seas were still running 30 feet, making it nearly impossible to jump from our vessel to the rope ladders that had been dropped for us. A cargo net was lowered to transfer the sick and injured, but after seeing three of our crew temporarily submerged as the huge ship rolled in the swell, the owner and I decided to climb the rope ladder. Timing our jump just right, we made it onto the ladder and then watched our boat drop 30 feet under us. As we climbed, the ladder swung out 15 feet from the steel hull and then came crashing back as the ship continued to roll. We’d climb 10 feet, hang on for the crash, then climb another 10 feet. The ship’s crew was above us yelling encouragement, and we finally made it to the top where we kissed the salty deck and met our rescuers.

Although the captain tried to tow the doomed sailboat, its lines soon broke and it disappeared over the horizon. During the next few days we were treated royally by the mostly Spanish crew as the ship headed to the Azores to drop us off. It was a time of great reflection, as I realized how close we had come to not making it. But it was also a time to think about what went wrong and what we could have done differently. While this story had a happy ending, it taught me several lessons about boating that I would live by for years to come. I’ve also made an effort to learn to use today’s technology to help avoid life-threatening situations in the first place. But ultimately, I learned that when you venture offshore, no one is more responsible for your safety than yourself.

Ten Lessons Learned

1. Never go offshore with strangers unless you can verify ahead of time that at least some of them have offshore experience.

2. Don’t be afraid to question the captain or owner about the safety gear aboard his ship.

3. Ask the captain or owner about key maintenance issues, such as engine service, through-hull inspections, rigging inspections, etc.

4. Get the most accurate, up-to-date weather forecast possible and know how to interpret the data.

5. Be prepared by knowing how to run the boat yourself, if necessary.

6. Familiarize yourself with your route by studying the charts ahead of time.

7. Learn the basic functions of the ship’s navigation and communications equipment before you leave the dock.

8. Carry a personal back-up GPS and laptop loaded with appropriate charts capable of running on self-contained batteries.

9. Go through a complete safety checklist with the owner and other crewmembers including MOB procedures, location of all through-hull fittings, emergency bilge pump systems, life jacket access, emergency communications systems (including flare kits), abandon-ship procedure, first-aid kit inspection, fire extinguisher locations, engineroom firefighting systems, location and working status of flashlights, and more.

10. Do not add to or make any last minute changes to the ship’s systems or electronics without a thorough evaluation and testing of this new gear.