J-Class Yachts

I had been waiting my entire life for this moment — or at least, since I had discovered sailing and Yachting magazine as a teenager. Instead of doing my homework, I spent hours poring over the pages where I found the legendary J-Class yachts of America’s Cup fame. I was captivated by their sheer size, the massive spreads of sail and the names associated with them: Lipton, Sopwith, Vanderbilt, Astor, Morgan.

And so, in the early ’70s, I was standing in what the English call a “soft day” … steady drizzle from a gray sky. I was at Wilf Souter’s boatyard in Cowes on the Isle of Wight. And Endeavour, Sir T.O.M. Sopwith’s J-Class yacht that came oh-so-close to taking the America’s Cup back to England in 1934, lay at the end of a long pier.

She was a forlorn hulk. Her blue topsides were faded and rusting, her majestic mast had been decapitated and the upper portion used as a mizzen, and the once impeccably varnished deckhouse was bare and rotting. But nothing was going to keep me from seeing her up close.

My first shock had been her dreadful condition. My second, as I walked out the long dock, was her size. Standing in the boatyard, she had seemed large but not amazing. The closer I walked, however, the larger she grew: I realized that I had been misled because she was perfectly proportioned. When I reached her side, she was simply … huge.

You cannot conceive of the size of a J-Class yacht until you stand next to one. With lengths up to 145 feet and beams of about 22 feet, these are long needles with immense overhangs of 50 feet. The masts loft up to 160 feet, the mainsail alone is more than 5,000 square feet, and, when racing, a J carries nearly half an acre of sail. It’s no wonder they raced with crews of 35.

The golden years of the J-Class yachts lasted just eight summers, with 10 yachts built between 1930 and 1937 to the Universal Rule introduced by Nathanael Herreshoff. Under this rule, yachts were alphabetically ranked by length, with J-Class meaning those with waterlines between 75 feet and 87 feet. Most J-Class yachts were built for the America’s Cup and, sadly, were scrapped in just a few years.

Because of a few daring (and deep-pocketed) owners, however, three original J-Class yachts were saved, in one case literally minutes from being cut apart. These magnificent yachts planted seeds in the minds of other yachtsmen intrigued by their classic lines, the immense power and that sense of tradition.

In 2000, a J-Class Association (www.jclassyachts.com) was formed, and at press time, no fewer than 11 J-Class yachts (old and new) are either sailing, under construction or in the design stage. For the first time in more than seven decades, as many as nine J-Class yachts will race as a class on the Solent in 2012, during the British Olympic summer.

The first J-Class yacht was Shamrock V, built in 1930 as tea magnate Sir Thomas Lipton’s fifth and final America’s Cup hope, and she was the only J built of wood.

The New York Yacht Club responded to Lipton’s one-boat challenge with four possible defenders: Yankee and Whirlwind from the Lawley yard and Weetamoe and Enterprise from the Herreshoff yard. Each was special: Weetamoe for being double-ended and introducing the soon-adopted double-headsail rig and the other three for having hulls plated with incredibly expensive Tobin bronze. Also, Enterprise sported a three-ton duraluminum mast built by the Glen L. Martin Aircraft Co., held together with 12,000 rivets. Though the defender eliminations were hard-fought, it was Harold Vanderbilt’s Enterprise that combined a fast yacht with impeccable tactics.

When Shamrock V met Enterprise off Newport, Rhode Island, in the summer of 1930, she went down in glorious defeats that gave the ever-gracious Lipton his title as “Best of All Losers.” Wearying of the Cup, Lipton sold Shamrock V in 1932 to Sopwith, the aviation magnate of Sopwith Camel fame, who used her to advance his own Cup campaign.

In 1934, Sopwith challenged for the America’s Cup with Endeavour, built by Camper & Nicholsons, which had practiced against Velsheda, a recently launched British J that was intended not as a Cup contender but as a private yacht.

Though the nation was deep in the Great Depression, Vanderbilt responded to the British challenge with Rainbow, which had the so-called “Park Avenue boom,” which was more than six feet wide. Endeavour proved to be fast and won the first two races, but because the professional British crew walked off for better wages, Sopwith had to sail with a crew of amateurs and lost the last four races to Vanderbilt.

Sopwith challenged again in 1937 with Endeavour II, and Vanderbilt once again took up the cause by financing Ranger, which was jointly designed by W. Starling Burgess and a 28-yearold Olin Stephens. During trials, Ranger won 35 of 37 races, and then swept the America’s Cup in four races, causing Vanderbilt to wonder whether she was so fast that she might discourage future J-Class racing.

It was, however, the harsh sound of Hitler’s jackboots marching across Europe as the United States struggled in the depths of the Great Depression that brought about the twilight of the J-Class era — not Ranger.

In 1935, America’s Whirlwind was scrapped, as was Enterprise, whose mast became the radio antenna for the Rhode Island State Police. Weetamoe went to the knacker’s yard in 1937, Ranger was sold for scrap in 1941, and Yankee’s last owner donated her to the Queen of England for the British war effort. The American J’s were gone.

Shamrock V passed to Sopwith’s aviation competitor, Sir Richard Fairey, who then, just before World War II, sold her to Italian publisher Mario Crespi, who renamed her Quadrifoglio. Hidden in an Italian barn through the war years, she was later saved by Piero Scanu, who acquired her just days before she was to be sawed up for firewood. Scanu sent her back to Camper & Nicholsons for a three-year refit that included a new teak hull and a birdseye maple interior. Bought from Scanu in 1986 by the Lipton Tea Co., she is now based in Newport and the Caribbean as a charter yacht.

Endeavour, Velsheda and Endeavour II survived the war, but Endeavour II was scrapped in 1947. Velsheda was left to rot in the mud of the Hamble River, and Endeavour passed through many hands (and survived a sinking) before I saw her moldering away in Cowes.

It’s at this point that the J-Class story gets interesting.

Bought for about $20 by two carpenters determined to save her, Endeavour was patched up and then, when money ran out, left as a rusting hulk at an abandoned seaplane base.

Enter Elizabeth Meyer, a feisty American yachtswoman and heiress who refused to see the legendary yacht die. She bought the wreck in 1984 and spent five years and untold millions to restore her at the Royal Huisman yard in Holland. Looking like new, Endeavour sailed in 1989 for the first time in 52 years!

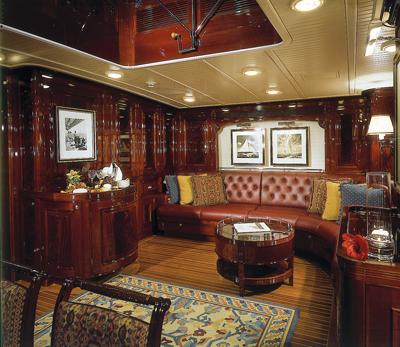

Also rescued from the mud in 1984 was Velsheda, once owned by F.W. Woolworth Co. heirs. She was minimally restored and used for charter work before ending up once again as a bare hull. Purchased in 1996 by another dedicated yachtsman, Velsheda underwent a two-year rebuild that included the tallest one-piece carbon-fiber mast in the world (at her relaunch in 1997) as well as a John Munford interior. This led to Velsheda, Shamrock V and Endeavour competing against each other at the Antigua Classics Week in 1998.

The sight of these magnificent yachts racing once again stirred the imaginations of several other yachtsmen who had the wherewithal and foresight to do something that many people thought completely mad: They commissioned the builds of “newold” J-Class yachts!

While only 10 J-Class yachts were built in the 1930s, there were a total of 20 designs created, which provides a priceless library of unbuilt designs for owners and naval architects. And, under the J-Class Association, there were rules set for building new yachts. Here’s a look at the “new-old” J-Class yachts.

Ranger

First out of the starting gate in 2003 was a replica of Vanderbilt’s 1937 Cup winner,_ Ranger_, this time in steel, from the Danish Yacht yard in Denmark, for an owner who had chartered Endeavour and become so enamored that he wanted his own J-Class. Starting with the original W. Starling Burgess/Olin Stephens lines, naval architects Paolo Scanu (son of the Shamrock V owner) and design firm Reichel-Pugh adapted the lines to Maritime and Coastguard Agency and Lloyd’s standards. Among the updates were a carbon-fiber deckhouse with mahogany overlays and a Glade Johnson classic interior using lightweight cored panels.

Hanuman

Next up was a replica of Endeavour II that launched in 2009 at the Royal Huisman yard. Though she had been called Endeavour II during construction, her owner, Dr. Jim Clark, chose to name her Hanuman in honor of a Hindu god. With the original Nicholson design updated by Dykstra & Partners of Amsterdam to include an Alustar hull and Rondal carbon-fiber mast with Park Avenue boom, she has been called a Super-J because she is at the upper limits of the class rules. Her 158-foot mast and immense sail area are balanced by 99 tons of lead that give her a draft of more than 15 feet. The polished French walnut interior, by Pieter Beeldsnijder, has an old-world charm.

Lionheart

The most recently launched is Lionheart, with an Alustar hull built by Bloemsma Van Breemen and finished by Claasen Jachtbouw, both in Holland. The lines were originally drawn by W. Starling Burgess and Olin Stephens for the Ranger syndicate of 1937, but they have been optimized by Hoek Design of Holland using performance analysis comparisons of existing J’s. She is the largest J-Class yet, with a length of 144 feet on an 87-foot waterline, giving her incredible 57-foot overhangs.

Atlantis

Holland seems to have become the hotbed of J-Class construction, and Hoek Design has three more J-Class projects under way there. A Dutch owner has commissioned Atlantis, which draws on the previously lost blueprints for a 1930s Super-J that was an advancement of Frank Paine’s earlier Yankee. According to Hoek, Atlantis will have the longest waterline, highest-aspect keel ratio and lowest wetted surface of any J-Class yacht. Again, the hull will be from Freddie Bloemsma’s aluminum yard and the yacht will be completed at Claasen Jachtbouw with a high-modulus carbon mast and fiber rigging.

Enterprise

Hoek Design has also been commissioned to create a replica of Enterprise. At 120 feet, she will be the shortest of the modern J’s, but under the J-Class Association handicap system is expected to be very competitive with an almost flush deck and tall sail plan.

Svea

Most mysterious of the “new-old” J-Class yachts is Svea, a previously unknown design from the pen of Swede Tore Holm. Hoek Design is finishing the design details for a Swedish-Dutch consortium, and construction will be shared by Bloemsma and Claasen Jachtbouw. Unlike other J’s, however, Svea will be flushdecked and will have a minimalist interior.

Rainbow

A “new-old” Rainbow, based on the winning 1934 Cup defender, is also in the final stages of completion at Holland’s Jachtbouw to an updated Burgess design by Dykstra & Partners. Built to Lloyd’s A-1 and MCA rules at Bloemsma, the new Rainbow will have a diesel-electric propulsion system using twin 350 kW generators rather than main engines.

Yankee

Just announced at press time is a replica of the Paine-designed Yankee. Dykstra & Partners is massaging the original lines of the 1930 contender, with the yacht about to start construction at Bloemsma for completion at Holland’s Jachtbouw in 2012.

Four decades ago on the day that I saw my first J-Class yacht, an old man was sitting quietly by the fireplace in the bar of the Royal Corinthian YC in Cowes, and his eyes warmed in remembrance of one particular summer in the ’30s.

“Aye, I remember the J’s,” he said. “I was just a young lad and was staying here on the island for Cowes Week. It was the last day of racing and I was sitting down on the waterfront. Suddenly out of the fog, a huge shape loomed up. … Aye, it was a J sailing back to her mooring! And behind her, almost in formation, were six more. As they swung into the wind, all the crews were proper in their whites as the huge sails came thundering down. But now,” he said sadly, “it seems there will be no more summers for the J’s.”

It’s a shame that man never knew that the J’s would be returning to Cowes this summer. And once again, there will be other youngsters on the seawall to revel in their majesty.